THE FOUNTAIN OF HATTEOS

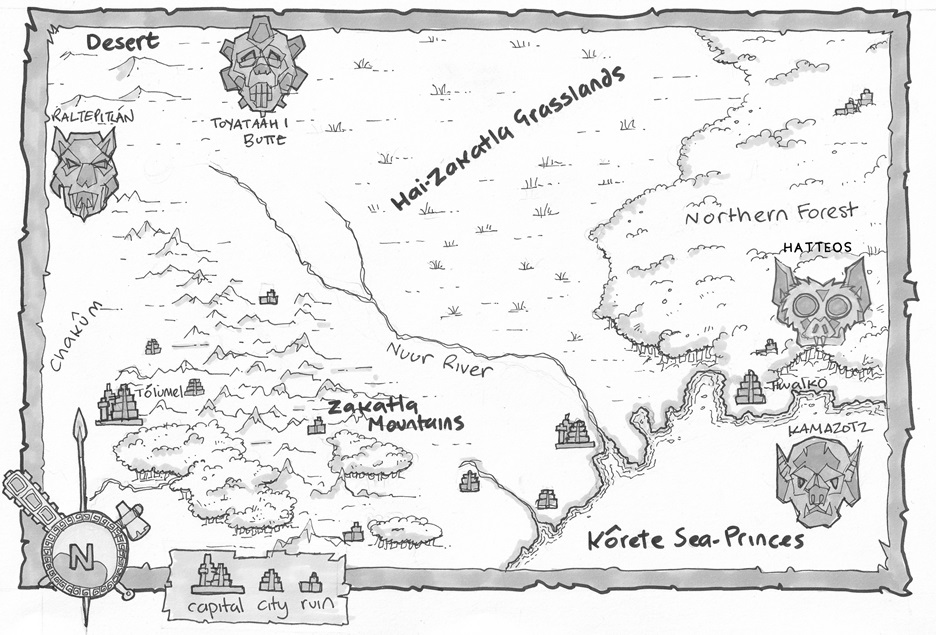

THE FOUNTAIN OF HATTEOS, A TALE OF THE AZALTÁN, by Greg Mele, Art by Justin Pfiel, Map by Simon Walpole

Having found neither the Turquoise Road nor the mercurial Chakumi to his liking, Sarrumos decides to return to the Kôrete city-states. He finds employment as a watch-captain in Tlawalko, a coastal city to the far east, founded by the Naakali that have never bent the knee to Azatlán’s imperial will. Ancient and proud, its financial success has long been rumored to come from its harboring of “sea wolves,” the many pirates who prowl the Altkalli Sea, preying on men of all nations. Any city with such a casual hostility towards the great southern empires should be a safe place for an exile.

1. Night Riders

For centuries, poets and minstrels had called Tlawalko the “jewel of the Altkalli Sea,” but Tanok saw the city as an ugly thing, clinging to the coast like a blood-fattened tick clung to a deer. Especially on nights like this, when the humid night air was so thick it felt like being wrapped in a wet, llama-wool cloak. He said as much to his partner, who was engrossed in throwing kakao-beans on the makeshift patolli board they’d drawn in chalk on the rampart’s walkway.

“Smells like a wet llama, too,” Tzijari, his fellow guardsman, said. Looking at his toss in disgust, he spat down onto the street below. “Your turn.”

Tanok snorted. He glanced briefly over the wall to scan the raised causeway of packed earth and crushed stone leading from the city gates off into the maize fields beyond, then reached for the kakao-beans. “Hate to humiliate you at beans again. Not right to take advantage of the elderly an’ all…ow!” He winced as the older man punched his shoulder, then smiled.

“Worth it.”

“I’m curious, Tanok: will it be worth it when your pay is docked and your two bare arses are publicly lashed in Magistrate’s Square because you were gambling while on gate duty?”

The new voice’s Naakal was more refined, the accent a southern, Azatláni lilt. The guardsmen scrambled to their feet, brushing their kilts smooth and standing at attention, spears held crisply out an angle in their right hands.

“Perhaps the vizier will be merciful and only make you breathe burning chili fumes,” the newcomer continued. He was only a little taller than the tribesmen, but his jadeite eyes, wavy auburn hair and angular features, especially the long, straight nose, marked his Naakali ancestry. The llama-wool cape tied at his right shoulder, and the bronze cuirass it partly covered, proclaimed him an officer, one clearly unimpressed by what he was witnessing.

“I’m sorry Watch-Captain Sarrumos,” Tanok stammered, eyes focused on a spot between his feet. “I…we…did not know you were on duty tonight.”

“I’m not—officially. I couldn’t sleep–the hot night air was clinging to me like…what was that? A deer tick?” the captain said, watching the men shuffle uneasily. “I decided I could either toss and turn on my sleeping mat or make myself useful; good thing, since I find the gate watch playing patolli, poorly at that, when–”

His reprimand was cut short by the sound of a voice crying out from beyond the wall.

Whomever it was, they were distant enough to render their words unintelligible, but the clear call to action was not. Captain and guardsmen alike ran to the edge of the battlements and peered through the crenellations onto the causeway below.

A lone man dashed toward the walls, a short bow in his hand, a near-empty quiver on his back. At first, Sarrumos thought he was alone, but then he saw mounted pursuers break from the distant tree line. He counted four, no, five—the rail chariot that thundered up the causeway had two men within, with three horsemen close in its wake.

“He won’t last long, him on foot and them’s mounted,” Tzijari said, giving voice to what they all thought. The runner was fast, but not faster than a horse, and clearly fatiguing.

“The gate!” the man called in Low Naakal. “Open! I bring…for…vizier!”

“Aye,” Tanok said, spitting again, this time over the wall, “he’s a goner.”

“Did you not hear him?” Sarrumos snarled, clouting Tanok in the back of the head. “He has something for the vizier. Open the gates.”

“Pardon, Captain—but how do we know that’s true? Look at ‘im! He’s some forest savage, being chased by Naakali. ‘Sides, vizier’s orders: gates remain sealed from dusk to dawn—no exceptions.”

“Gods Below! Good thing the vizier pays me to think, not you two idiots. Open the gate! Now!”

“All right, all right, Cap’n,” Tzijari said, “but they’ll have him ‘fore we get them open.”

Sarrumos glanced over the wall. The archer was still running full-out, but slowing, the chariot rapidly closing the distance between them. “Just get the gate open, and the guards ready, I’ll buy him some time.”

Turning, he drew an arm-length sword of keen-edged bronze and hacked into the ropes supporting the drawbridge’s counterweights. Three blows to the first rope, two to the second, and the thick hemp parted, sending the short, wooden bridge crashing to the ground, over the deep ditch abutting the walls.

“Captain, what are you—”

“Just get that damn gate open!” Sarrumos cut him off. Sheathing his sword, he threw the severed rope-end over the wall, then swung himself over as well.

2. Prince Kouras

Sandals slipping on the stones, Sarrumos bounced off the city wall, clinging tenaciously to the thick rope, leaving ample time to curse at his own impulsiveness before successfully getting his feet back under him to scramble down the rest of the way. As soon as his feet touched the ground, his sword was back in his hand, and he was running down the causeway towards the archer—who came to a halt when he spied Sarrumos charging towards him.

The beleaguered man was clearly a northern barbarian, and as distinctive for his homeliness as his outlandish appearance. He was a little taller than Sarrumos and rangy, his coppery-colored cheeks badly scarred from some childhood pox, the hooked nose oddly wide and round at the tip, as if it had been badly broken in the past. His hair was shaved to the scalp on both sides of his head, leaving a long crest like a horse’s mane that fell down his back and was dyed a deep, garnet red. He wore only moccasins, a deer-skin breechcloth, and long, fringed, deerskin leggings tied to the former’s waist cord; his naked, wiry torso was slick with sweat. A formidable-looking, curved war-club hung from a baldric, but it was the bow and a pair of flint-tipped arrows that filled his hands now.

The Northman slowed further, eyes wary, clearly appraising if the newcomer was friend or foe. The moonlight caught and refracted in a fist-sized, citrine stone set in gold fittings that hung about his neck from a heavy, gold chain.

“Keep running,” Sarrumos shouted, “they’ll have the gates open when we get there.” He glanced back at the wall, where the wooden gates remained sealed. I hope.

The archer nodded, panting, but the roadway had already begun to thunder as the chariot and horsemen drew close, small, crushed stones tumbling loosely down the causeway.

“A fine chase—but one, I think, that has gone quite far enough,” a deep voice said.

Directly between Sarrumos and the rising moon, two imposing figures stood inside an expensively crafted war-chariot pulled by a pair of magnificent, chestnut horses with thick black stripes on their haunches and legs. The charioteer was a mixed-race man, one eye forever sealed by a long scar that split the right side of his face. But it was the chariot’s passenger who held the captain’s attention. Dressed entirely in black, the face beneath the wide-brimmed hat was aristocratic, its angular features handsome if not for the mocking sneer that curled voluptuous lips over a pointed beard, like Sarrumos’s own. The younger man saw nothing good in the way the nobleman’s amber-brown eyes sized him as an owl might a rabbit.

“My name is Prince Kouras. You are a guardsman in service to the city’s waketa.”

“The waketa is dead. Aranaro, his vizier, rules now as regent.”

The sardonic smile widened.

“Indeed? In a fire, perhaps? A pity, but no import now. You serve the city, and are thus charged with apprehending thieves, such as this red-skinned scum.” The words were scornful, bigoted, yet Kouras’s manner was mild and nonchalant. He smiled politely, as if discussing the weather with an imbecile.

The ‘red-skinned scum’ turned to look at Sarrumos but did not relax the arrow he had trained on Kouras.

“I am on the vizier’s business,” he insisted in thickly accented Low Naakal.

“There, you see—there is no thievery here,” Sarrumos said with equal, feigned nonchalance. “Perhaps, the Great One would like to join us within the walls, and we might discuss this with Aranaro-tzin himself?”

“Oh, I will ‘discuss’ things with the vizier in due course. But for now, I will have the bauble this thief stole. You, guardsman, will either remain as you are or,” he casually laid aside his cloak, revealing a sword’s jeweled hilt, “the city of Tlawalko shall have one less watch-captain. The choice of which matters not to me.”

“It rather matters to me,” Sarrumos replied, listening to the sound of the gate opening behind him at last. Gods Above, would you idiots hurry? “Of course, if our barbaric friend here is any kind of shot, he might put an arrow through you before that happens.”

Kouras smiled. “He may try.”

“If I try, I will succeed,” the homely archer replied matter-of-factly.

A tense silence followed, each side considering their options. Glancing back at the city, its slowly opening gates almost a hundred yards away, Sarrumos’s shoulders slumped in defeat. Two men on foot against five, all mounted, was decidedly bad odds. He turned to the man he’d attempted rescuing.

“I’m sorry,” he said, shaking his head, before turning to look up at the smirking nobleman. He stepped aside.

“Excellent,” Prince Kouras murmured, his charioteer edging them nearer.

This slight relaxation of attention was all Sarrumos needed. Wordlessly, he drew his dagger with his left hand and thrust it into one of the chariot horse’s striped haunches. The wound wasn’t deep; his intent wasn’t to lame the beast, but to startle it. With an awful bellow of pain, the horse reared in fright, the equally surprised Prince stumbling, almost falling from the chariot as his driver fought to regain control.

“Achatl!” Kouras roared.

The larger of the mounted men-at-arms, brandishing a wicked-looking axe, twitched his reins and came rushing towards them.

“Shoot him!” Sarrumos cried, but the man was already tumbling backwards off his mount, a feathered shaft buried deep in his throat. A second arrow went speeding, not towards another horseman, but to his mount, burying itself in the animal’s leg, the lamed animal letting out a scream of rage and pain.

Sarrumos sprinted for the dying Achatl’s horse. Leaping into the saddle, he turned the wild-eyed beast’s head in the direction of the city.

“Get on!” he barked, extending a hand. The Northman took it, and Sarrumos hauled him up behind him. Then, digging his heels into the horse’s flanks, he shot off for the gate. Prince Kouras, his driver at last in control of their horses, pursuing with his two remaining servants.

They raced down the causeway straight towards Tlawalko’s walls. Sarrumos had a head start, but their pursuers were not hindered by riding double; their only hope was for his guards to lend support in arms before they were overtaken.

Kouras’s chariot had closed to within thirty yards as they reached the city gates, which were finally swinging opening. Leaning low over his snorting horse’s neck, the Northman’s arms tight about his waist, Sarrumos drove the animal straight through the opening without slowing, thundering past half a dozen guardsmen who scrambled out of his way. Turning in the saddle, he could see over the barbarian’s head their pursuers were still outside the city, Kouras glaring angrily at the advancing soldiers, though the nobleman made no effort to flee.

“Prince Kouras,” one of the guardsmen declared, clearly recognizing him, “you and your men will throw down your arms and dismount!”

Ignoring the call for his surrender, Kouras began murmuring, hands spread wide as if in prayer, his face creased with concentration. A breeze began to blow, rising with preternatural quickness into a strong wind.

The soldiers began advancing through the gate. The prince’s amber-tinted eyes opened, the rims of the irises seeming to glow with a lambent light, his shoulder-length hair whipping in the growing wind. His witch-gaze falling on the heavy city gates, Kouras lifted his left hand, fingers splayed wide, then clenched them sharply, raking down.

“Nuwachix and Kwaxcip have mercy!” the northern barbarian gasped from behind Sarrumos, who had turned their horse about so they could see what transpired. “The gate!”

With a terrible cracking sound, the heavy timbers split, their hinges tearing free from lintel and arch. The charging soldiers heard too little, and their captain’s cry came too late. As the wind whipped and howled, the huge, wooden doors snapped free of their moorings and came hurtling to the ground, crushing three of the guardsmen flat beneath their vast bulk, sending a fourth tumbling to the ground. The two soldiers still standing hesitated, unsure what to do, then ran to their fallen comrades.

The corner of Kouras’s mouth curled upward in a smirk, his hand wiping distractedly at a bloody rivulet that ran from his left nostril. Then, ordering his driver to turn the chariot, they rode back down the causeway and into the pine groves beyond.

3. The Fresco Speaks

Midnight-dark cloak billowing behind him like a churning storm cloud, Prince Kouras strode through the gates of the small fortress that was both his inheritance, and in recent years, his exile. Perched high on a craggy hill, it commanded a splendid view of the surrounding countryside and the endless forests to the north. But the Prince was in no mood for views.

“Ikal!” he shouted, and a short, stout man came running to his side.

“Great One?”

“That wretched, Hichitwa savage escaped, Ikal! He’s safely behind Tlawalko’s walls now. That wretched vizier, Aranaro, set his guards came after me—as if I were some foreign lout! Can you imagine? Well, I punished them for their lack of loyalty.”

Ikal nodded approvingly at his master’s words, but the good humor died as he came closer to his master’s side. “Great One,” he stammered, “your face ….”

Kouras’s right hand touched his cheek and a look of fear flickered in his honey-colored eyes.

“It is nothing!” he snapped. “All things come with a price. What is the proverb: He who searches for pearls must be prepared to dive deep? Even now, that skin-clad savage is taking my amulet to Aranaro. I must know what passes between them. Have the servants bring me mescal and strong tobacco.”

“Of course, Great One,” Ikal demurred, hurrying after his master’s retreating form.

***

“As strange as is the tale you tell, Captain,” the vizier said, once Sarrumos had finished relating their adventures at the gate, “I would believe all you say—even were not my guards witness.”

They were deep within the royal residence, which sat atop a low, man-made acropolis of piled earth and stone. In the half-year Sarrumos had served in the Tlawalko guard he had never so much as glimpsed the palace’s inner chambers, but upon seeing the archer and the heavy amulet he held, the royal guards had admitted them at once.

They were in what seemed more a scribe’s study than a lord’s. Lit by many clay lamps, the walls were covered in intricate frescoes, some cracked and badly damaged by age. A low table was covered with scrolls and clay tablets; more of each, and bound codices besides, were piled haphazardly on a tall set of shelves beyond.

Standing beside that table, leaning on a mahogany cane, was Aranaro, Tlawalko’s vizier and regent. A tall, pale-skinned Naakali, it was nearly impossible to tell his precise age. Such was never easy with purebloods, whose lifespans were sometimes near twice that of a normal man, but in Aranaro’s case, such considerations were made even harder. Not only was the man completely bald, with little more than wisps of dark hair for eyebrows, but he was badly scarred, the right side of his face and neck twisted in an ugly mass of pinkish-white burns that pulled one corner of his mouth into an ironic grin. His right arm curled tightly against his chest, and what Sarrumos could see of the hand within the cotton robe’s wide sleeve suggested the limb had fared even worse than its owner’s face.

“I believe you,” Aranaro noted, placing his cane on the table so he could hold the heavy amulet aloft in his good hand, “because it was I who sent Ollad to recover this from Prince Kouras. I have long known that monstrous man capable wielding all manner of unnatural sorceries.”

The Northman—Ollad—said nothing, but his frown deepened, leaving Sarrumos to wonder how much of that knowledge the vizier had shared with his agent.

“Might I ask why, Great One? Princes ever covet each other’s holdings, of course, and Tlawalko is —,” he hesitated.

“Weakened by her lack of monarch? You can say so freely; it is on the thoughts—and lips—of many in the city. When Ekhinos-waketa died, he knew his two sons were but youths, and his daughter a babe in arms, so someone must rule as regent. His brother was already exiled for treason; I assume you now have some hint as to why.”

So, Kouras was a prince—of Tlawalko!

“Of course, the boys’ mother was not suited. Which left only me.”

Sarrumos nodded, working to keep his face impassive. The Naakali were a conservative people, but those of the Korête free cities were outright reactionary. Every lord kept not only a wife, but multiple concubines, and a woman’s legal rights were defined, protected, and prosecuted through her father, brothers, or husband. The idea a dowager queen might serve as regent, common enough in the Empire, would be unthinkable here in the north.

Gods forfend they let the heir’s mother see to his inheritance, Sarrumos thought in disgust. But for once, he was wise enough to hold his tongue.

“Ekhinos made me heir to what he said were two sides of one great secret. The first is here in this chamber.” The vizier, his grey eyes gleaming, set the amulet down and took up his cane, moving with a decided limp towards one of the damaged frescoes. “These paintings recount a legend brought to Tlawalko with her first settlers,” he said.

Sarrumos studied the wall carefully. Once, there had clearly been some grand, colorful scenes covering it floor to ceiling, but so many sections had been burned that it was impossible to establish what had been truly depicted there.

“If this is the city’s greatest inheritance, Great One, I fear it may remain a mystery,” he said wryly.

“Yes, precious little remains,” the vizier agreed, his eyes taking on a far-away look, as he absently stroked the twisted flesh that covered one side of his chin and neck. “The city is ancient; these walls were painted twenty generations ago and have seen their share of misfortune through the centuries. Nevertheless, much was written about them by past waketas and their viziers. Once Ekhinos breathed his last, I summoned the embalmers and then hastened here to study the fresco’s clues. As I entered the room, I was engulfed in flames.”

“Someone set the room ablaze?”

The lopsided mouth curled further, twisted skin stretching painfully.

“No, I was engulfed in flames. The hand which clutched the handle, its arm, bursting with fire—from within.”

“A witch-fire?” Ollad asked in awe.

“Yes. It reduced me to this scorched patchwork of man and burnt meat you see before you.”

“And this was done by Prince Kouras?” Sarrumos asked.

Lord Aranaro nodded. “I only suspected, but after tonight’s events I will accuse him openly.”

“The Great One said the Waketa-Who-Was bequeathed two things,” Sarrumos nudged.

“Yes, and the second was something fire could not destroy quite so easily,” From beneath his long tunic, the vizier withdrew a heavy golden chain, from which dangled a twin to the amulet Ollad had just delivered. “Indeed, I believe it is why the fire could spread no further along my flesh, for once the fire reached my chest, I felt a quenching cold fill my limbs, and it was doused.

“The physicians say it was the gods’ mercy I survived,” Aranaro said ruefully, turning the amulet about in his hand thoughtfully. “I rather think neither mercy nor the gods involved.” The vizier seemed to come back to the moment, and blinked, as if clearing his eyes, or memory, of unwanted dust.

“No matter. What is known is that since Tlawalko’s founding,” Aranaro explained, “the two stones have been kept divided—one in the hands of the waketa and the other in that of his heir. They are part of a puzzle that reveals our secret in full.”

Despite himself, Sarrumos was excited. But he also was wise enough in the ways of rulers to be suspicious whenever they were too quick to share their secrets.

“But what is to be revealed, and why is Prince Kouras so sure it will give him the kingdom?”

“Power, my friend; an invincible power that might give Kouras not only Tlawalko, but much more besides.” Aranaro studied him for long moments as if debating how much to reveal. “Your accent and manners are those of the Azatláni court. And the name Koródu is an old one in the imperial eastlands.”

“I…,” Sarrumos stammered, caught unprepared. Tlawalko was far from the Empire’s influence or machinations; he’d never expected his name to be of notice. “The Koródu are an old family indeed, Great One; in that time, its lords have produced many by-blows such as me.”

Ollad’s eyes turned towards him, the Northman cocking an eyebrow in interest as if seeing him for the first time.

“Peace, Sarrumo-tzin,” the vizier said, applying the noble’s honorific to his name. “Whether you are the errant son of Koródu’s wannax, or some clan bastard given the gift of the family name is no concern of mine. Either should have taught you a certain degree of prudence, when dealing with the affairs of power, and what I share now must not be spoken outside this room. Am I understood?”

“As regent, Aranaro-tzin is Tlawalko; I swore to serve the city, and thus him.”

The burned face studied his carefully, glanced to Ollad’s impassive, homely one. After a moment, the mouth’s fire-curled corner twitched into something like a smile. “Very well. What do you know of Hatteos the Enshrouded?”

“What Naakali has not heard of him? Hatteos was brother to Tzeas Stormcrow and Posedowas the Navigator; the heroes who led the Godborn Tehanu forth from the dying continent of Iperboritlán to Tehanuwak when the latter was ground beneath the Great Ice.”

The vizier waived his good hand impatiently. “Yes, yes, as you say, every Naakali knows that much. But what else did you learn in your lessons?”

Sarrumos frowned, trying to remember dry tutors’ lectures washing over a child lost in daydreams of adventure. “The exiles came first to the Great Isle, where the Mihowaka dwell now. There, Posedowas remained, and built the Tehanu’s first city. Tzeas sailed west and found the mainland, which he named Tehanuwak, after the Godborn themselves, building his city on the banks of Teotepetl, the holy mountain…”

“Yes, whose ruins modern Azatlán gazes upon daily and thus believes itself superior to all thereby. But hard as it is for an Empire man to imagine,” the vizier said with a wink, his scarred lips twisting to form an actual smile, “it is not the God-King Tzeas we care about tonight, but his brother, Prince Hatteos. What of him?”

The younger man scratched the back of his head furiously. “Hatteos was the youngest brother, with the fewest followers. He also was said to be adept at magic; his title ‘the Enshrouded’ or ‘the Hidden One,’ refers to that. He explored the northern shores of the Altkalli Sea, though not so far west as we are now. Legend says he came to the mouth of a wide river and sailed northward into the great forests. Somewhere therein, he and his followers built their own city, Khalkûm. Hmm…that’s all I recall.”

Lord Aranaro nodded his approval, then winced and rubbed gently at the burned flesh of his neck. Seeing Sarrumos’s concern, he shrugged. “Pay old wounds no mind. Yes, Khalkûm. Which still flourished two-thousand years later when Tenoch founded Azatlán. We are concerned tonight with the secrets Khalkûm held before its own demise.”

Turning back to the fresco, he leaned forward and used his good hand to trace part of the remaining image. “You see here, at the center, is a fountain?”

“Yes…”

“And this, here, about its base are depicted antlers.”

“A deer, Great One? I am sorry, I do not know any legend of stags and fountains in connection to Hatteos or Khalkûm.”

“No, not a stag,” Ollad interjected. The northern barbarian had thus far been a man of few words, standing awkwardly silent as he listened to the two Naakali speak in a language not his own. Now his eyes flashed with animation. “It is the olobit; the Guardian of Secrets who dwells in Ho’Kae’Keesh-et-Hanyip, ‘the Abandoned House of the Pale People.’”

“And this olobit is…benevolent?” Sarrumos was young, but in the years of his exile he had already encountered things once men, creatures of elder ages and demons from the outer dark and had learned, mostly to his detriment not to discount legends out of hand.

The archer shrugged.

“It is wise and ancient; its ways are its own. Sometimes it gives counsel to men, sometimes…”

“Yes?”

Another shrug. “Sometimes those who seek the olobit do not return.”

Wonderful.

Sarrumos looked back to the vizier, whose frown at Ollad’s words mirrored his own. “And this olobit is a revered legend and treasure to Tlawalko’s lords because…?”

The vizier shook his bald head. “It is not. It is what it guards…or rather, what it may guard knowledge of: the Fountain of Hatteos.”

“What does this fountain do?”

“That I do not entirely know. It is said that Hatteos possessed powers of insight and prophecy beyond mortal ken, living for centuries after his brothers had perished—an impossibly long time, even for the Tehanu, whose lifespans were so much longer than our own. I cannot say for certain if the Fountain was the source of those gifts, or if the legends are even true, but what matters is that we solve this mystery before Prince Kouras does.”

Sarrumos turned back to the two amulets lying on the writing table. “And these amulets then,” he said. Forgetting he was a mere guard captain, he snatched them up to examine them more closely. “What of them?”

“As I said, they are two pieces of a tripartite puzzle—a puzzle that leads to the Fountain itself.”

“But where is the third?”

The vizier met his eyes and held them.

“What you see here,” he pointed with his cane to a badly peeling bit of paint two hands-breadth beneath the antlers, “once depicted a golden chain, and from it hung a shape, not unlike the amulets you hold…”

“You think it is with the olobit…,” Sarrumos said, comprehension dawning. Lord Aranaro merely nodded.

“I do, and with all three pieces, the path to the Fountain will be revealed. Fortunately, Ollad is of the Hichitwa, whose tribe have long dominated the forests east of the Great River. Khalkûm’s ruins may be lost to us Naakali, but the Hichitwa know just where it, and the olobit, may be found.”

The younger man turned to look at the Northman for confirmation. Instead, he found the man unslinging his bow, his eyes filled with the intense glare of a warrior entering combat. With a gasp, the captain stepped in front of the vizier, hand reaching for his sword.

The Hichitwa lashed out with his bow as if it were a staff—yet his target was not the young Naakali, but the top of a bookshelf. To his astonishment, Sarrumos saw a small figure, leap the bow-shaft and land nimbly on the ground. It was a spider, the size of a man’s hand, such as were found in the western deserts—only an all-too-human eye perched in the center of its thorax and rotated freely, scanning the room to take each of them in.

“Gods Below!” Sarrumos swore.

There was no time for a reply. The spider-thing creature had recovered from the blow and was now scuttling rapidly across the room on striped legs towards some hanging draperies.

“It mustn’t escape!” cried Aranaro, striking wildly at the creature with his cane. Sarrumos lunged at the little monstrosity, but it darted beneath his feet and scurried towards the door.

“There it goes!” he shouted, sprinting across the room. He leapt for it, landing hard on the stones, but the small creature sprang free of his grasp, leaping the height of a man toward’s the wall.

There was a buzzing hum, and it fell, transfixed mid-leap by a flint-tipped arrow. By the time it struck the ground, nothing of the creature remained but a tangled mass of dried tobacco leaves, twigs, and sand.

“What in the name of the Nine Hells was it?” the young captain demanded.

“A sorcerous creation,” breathed Lord Aranaro. “Kouras’s spy. We must assume he has heard all we have said and now knows at least as much as we. Which is why I must find the truth of the Fountain for myself first.”

“It is to be a race then,” said Sarrumos, excitement gleaming in his eyes, eager at the thought of being free of the tedium of patrolling walls and commanding ignorant, profoundly unimaginative guardsmen—for he was still young.

***

Kouras rose with a gasp from his sleeping mat, clutching at his back, frantic to pull the arrow free. Then, he remembered it was not he who had been shot.

Looking down at his hands, he noted the skin seemed thinner, the veins more pronounced, the nails yellowed. He put it from his mind. There was time enough for what he must do. Afterwards, the Fountain would set all a-right.

“Surem!” he cried, bellowing for one of his henchmen. “Tell my captain to ready the ship; we must sail with the next tide!”

- The Chase

Aranaro looked back across the pentecoster’s stern to the dark shape that hovered at their edge of vision. It was their third day at sea, and they had greeted the dawn with news of a distant ship following in their wake. He shook his head in dismay.

“It’s Kouras,” the Tlawalko’s vizier said, clearly worried.

“Bah! It’s one galley,” snarled Khossos, their hired Naakali sea captain. “I’ve sent plenty such beneath the waves. Let me turn us about and sink him!”

Though no one had said as much, it was clear to Sarrumos from the moment he met the ship’s captain and his crew that he was no honest merchant, but one of the many pirates that used Tlawalko as a safe port-of-call for selling their ill-won cargo. Presumably, the vizier had chosen the man for some combination of greed and willingness to ask few questions; apparently, neither modesty nor prudence had been virtues in consideration for the job.

“The prince is more than just a man, Captain Khossos,” Sarrumos counseled. “Don’t be too quick to seek a battle in which we might be sunk ourselves.”

“We have a lead over him,” the vizier said. “Surely we can maintain it.”

Khossos looked doubtful. “It depends. That’s a fine-looking ship—she has us in the size of her sail, so if the winds hold, it helps them over us. Still, look you east, there’s mist hugging the coast.”

“I don’t see how that helps us,” the vizier said.

“Hah, spoken like a land-clinger! It helps us because in a mist, no one wants to sail close to the coast without knowing just where any shoals or sandbars might be. And that is hard to do without slowing your pace. Fortunately, I know these coasts well—and my balls are bigger than any captain in these waters,” He turned back to his steersman and cried, “Bring us in closer to shore—we head for the mists!”

“His balls or his arrogance?” Ollad muttered quietly.

Sarrumos looked at the Hichitwa archer and sighed, “Often, one seems to accompany the other.”

The ship cut inland, towards the growing mist.

***

Three days later they were still no closer to overtaking their enemy, and it was clear to Prince Kouras that they never would. He’d exhausted himself by calling spirits to rid them of the mist his captain found so frighting and stirring the winds to fill their sails. Yet still the other galley remained the smallest shadow on the horizon.

The exiled prince reminded himself he needn’t reach Khalkûm first, only be first to the Fountain. And that could be achieved by letting that fire-roasted scribe do much of the work for him.

The ship’s captain was surprised when the prince haughtily called for him to make for shore, but there was no way Kouras could perform the dark alchemy he intended in a galley’s rocking hull.

Making landfall, the men happily lay down on the white sand and stretched ship-cramped legs, as the prince motioned for Surem to gather his belongings and follow him into the nearby greenwood.

“Find me game,” the prince barked, distractedly, as he set about unpacking his tools. Surem scowling, set into the trees to see what he might flesh out.

“A rabbit is better; live best.”

Despite years of service, it was the first time Surem had beheld his master’s sorceries, and sometime later, the stout, one-eyed warrior stood guard nervously while Kouras mixed herbs, mud and what seemed dried parts of different animals in an engraved copper bowl. It was a work of hours, not minutes, but at the end, there was an ugly, little winged mannikin of what might be a crude owl, its features no more sophisticated in detail than a child’s poppet.

Burning copal and incense, the sorcerer-prince cut the rabbit’s throat, letting it bleed out in the brazier, then blew the rising fumes over the ugly little form, chanting in the rolling, sibilant syllables of classical Tehanu. Ignorant of their meaning, Surem could merely gawk as the fumes passed over the mannikin, solidifying and refining its form, transforming mud and muck to feathered flesh. For a moment, he thought the homunculus would rise with life, but then it collapsed in on itself, leaving only a pile of dust.

But something had come. Appearing from nowhere, on stout wings it descended toward them, backlit against the rising moon, a horned owl, large for its kind. It snatched the rabbit from the prince’s upthrust hand and landed across from their fire, hungrily devouring it. When it lifted its blood-soaked face, a long, tongue agitatedly flicking the air, Surem stumbled back and gasped. This was no owl.

Smiling with satisfaction, Kouras stretched out a bare arm, and cut his wrist with a dagger, the bronze drawing a red line just below a similar, half-healed wound. The bird-creature jumped on the inviting arm and clung there, lapping at the wound, its face transforming as it drank like one of the vampire bats from the distant south.

The sorcerer stroked his creation’s sharply pointed ears as it fed. “You are my eyes and ears, little friend. Find Aranaro and learn where he might go. Then, you and your may have them.”

At that, the creature flapped its owl’s wings violently, launching itself into the air. Kouras watched it rise, circle overhead then wing away to the east, until he lost sight of it against the sun. When he turned to his astounded henchman, his face was even more heavily drawn and lined than before, strands of silvery-gray hair marking his temples where none had been before. Yet his face wore a wide, triumphant smile.

“You see, Surem, our foes cannot hide from me. The night will have its ears and the day its eyes.”

4. Temple of the Olobit

Their ship struck north up the slow-moving river. Behind him, the seamen concentrated on rowing, as Captain Khossos stood in the prow, calling guidance to the tiller, lest they beach themselves on one of the many sandbars and mud-fields that shaped the Great River’s wide delta.

Sarrumos understood now why the Hichitwa simply called it ‘the Great River’—besides the sea itself, he had never seen such an extensive body of water. Although Naakali civilization has been born on an island, much of their modern empire lay deep inland, and Sarrumos had spent little time at sea. He had thought the quick-flowing River Nuur that separated the Empire and the Korête cities a mighty torrent, but now it seemed a mere trickle compared to the inexorable flow of water creating this twisting delta of water, mud, and sand.

He asked Ollad how far north the Great River flowed, but the Hichitwa shrugged in reply. “Beyond any land my people know, perhaps near where the ice never melts.”

“What a beautiful land!” Lord Aranaro exclaimed. “Truly Ollad, it must have been hard to leave this place behind!”

Sarrumos could only agree, for he had never seen so an exotic coastline, with such a verdant overgrowth of thick greenwood. His own homeland was a place of rocky hills, scattered groves, and carefully manicured orchards, but here was a mélange of cypress swamp and dense pine forest; a veritable green fortress, through whose towers a perpetual humid mist added an air of mystery.

The Hichitwa archer regarded the vizier, a variety of emotions playing across his homely face. “It was…difficult.” His jaw took a set, and he stood straighter. “It is done now.”

“Look!” one of the other guardsmen cried, pointing to the northwest. Through the treetops stood the familiar peak of a Naakali pyramid-temple, or something much like it. In a matter of moments, the men could see the river’s western bank was dotted with great chunks of stone—piers and outbuildings reclaimed by time.

“Stand by to land!” called Khossos, leaping into the waist-high water to help pilot the pentecoster ashore.

Once their work was done, and the ship at anchor, a small party was chosen to head up the beach and into the thick vegetation. The vizier had intended the search party to consist of Ollad, Sarrumos, his guards, and himself, but Captain Khossos insisted on coming along, bringing a small party of five sailors besides.

Protecting his interests in any treasure, Sarrrumos surmised as they gathered their gear.

The vizier decided it not worth alienating the man who would bring them home again, so Ollad led all fourteen men upriver, into the forest. Though thick, there were broad swathes of newer growth, and the earth beneath their feet was nearly level, as if they walked an old roadway nature was over-growing.

They soon found more ruins, all scattered and choked with greenery, including the pyramid-temple they had glimpsed through the trees. A still, eerie silence pervaded the atmosphere, so that only the sailors’ coarse-humored chattering filled the air. It had been a settlement, for certain, though surely not so grand as a city.

“My hometown is bigger than this,” Khossos said in disgust.

“Perhaps this is not Khalkûm, but an outlying suburb,” Aranaro suggested, looking to Ollad for confirmation. The Hichitwa archer shrugged.

“I have never been to Ho’Kae’Keesh-et-Hanyip and lead us based on the words of others. But it is said that from a place of broken stone houses one leaves the Great River and marches straight towards the setting sun. We will come to a much smaller, twisting river, and from there we shall see the trees fall away and the Old One’s abandoned city.”

Aranaro nodded. “Such is more than I know. Lead on!”

The ancient roadway rapidly decayed in quality, and soon the company was pushing their way through thick, old-growth forest; Ollad looking for landmarks recalled in Hichitwa legend. Twice it seemed they were lost, foundering in swamp and forest, but each time the homely Northman found his bearings once more and led them through.

Late in the afternoon they at last reached the city. Though he’d endured the hike stoically, the vizier leaned heavily against one of the soldiers, panting, rubbing at his leg with his good arm.

“Gods Above!” Sarrumos gasped, looking at what lay before them.

He had been told the northern forests were filled with skin-clad savages, living in small villages behind wooden palisades, their chiefs dwelling in huts no greater than those of the miserable hunters and fishers they ruled. Perhaps it was so, perhaps not, but whoever had built Khalkûm clearly had a far greater vision, for even in death, the city impressed and humbled its visitors.

The entire settlement was elevated, its stone homes—many fallen now into tumbles of rocks, the thatched roofs long-since rotted away—built on six, vast concentric half-circle mounds, each taller than a man, and radiating out from a broad, circular plaza. The plaza abutted a small river but was joined to the residences by five paved avenues that transected the mounds and were accessed by stone steps, though the earth had largely reclaimed them. Beyond the rings lay a series of larger, raised mounds, and upon them massive, stone buildings that to Sarrumos’s eye recalled Tlawalko’s palace. But it was not to these, but to the lone mound at the heart of the plaza that Ollad pointed.

“There is our task.”

Topped by four great crumbling stone faces, a massive square edifice squatted atop the earthen mound like some half-formed creature of an earlier age, its grandeur long faded by the relentless ravages of time.

As the men approached, a flock of exotic, long-limbed birds with brilliant pink plumage abandoned the river and took to the air above. Once they were confident the newcomers were no threat, the birds settled along the banks once more, standing strangely on one leg, heads cocked to one side, watching these strange, featherless interlopers with curiosity.

“This plaza is packed clay,” Sarrumos noted as they walked towards the mound.

“It looks like a tzungee court,” Ollad said matter-of-factly. Seeing the blank stares that drew he explained. “It is a game popular among my people. Two men, one from each team, start off upon a trot, abreast of each other; one rolls a little stone ring before them and each hurls his tzungee-stick after it, trying to capture….”

“That sounds like a stupid game,” Captain Khossos interjected.

The Hichitwa turned and looked at him, his face a mix of outrage and disgust, “It is not just a game; it ties us to the Sacred Time of the gods, when –”

“Like I said, sounds like a stupid game. A wrestling match or a horse race, that’s a competition!”

“Alright, whatever the merits of the game, Khossos,” Sarrumos interrupted, “if it is a Hichitwa sport, why is there a chunkey court in an ancient Old Race city?”

Ollad shrugged broad shoulders. “Not “chunkey”—tzungee. And tzungee is not just a game, it is a sacred retelling of the war between the worlds Above and Below. We build our courts at the base of our greatest temples.”

“Then let us hope that is what we see now,” Lord Aranaro noted, gesturing to the steep, earthen mound before them.

The broad stone steps that had been set into the artificial hill were covered by the detritus of years and overgrown with grasses and creepers; some steps subsumed into the mound, others cracked, pushed up and rejected from their earthen foundation. It was slow-going, particularly for cane-using Aranaro. A guardsman joked it would be ironic to have come this entire way only to tumble to their deaths, but his humor fell flat, and he silently returned to using his short spear like a walking staff to steady his ascent. Reaching the mound’s summit, they could see the entire lay of the city with its grand plaza and radiating streets.

“It is like a rising sun: the streets its rays, extending out in waves from this plaza,” Aranaro mused.

Sarrumos found the comparison apt but was more focused on the shrine before them. It was not as austere as it had seemed from the ground, the intricate carvings of the entranceway showing traces of what must have once been a brilliantly painted edifice. Strangely, a pair of enameled panels, set into the walls on either side of the doorway looked untouched by the long years of abandonment. Each had a bright blue field depicting a pair of rattlesnakes with long, wolfish ears. The wolf-snakes were tied together tail-to-head, so that their bodies formed a ring encircling a raised hand with a white eye in the center of its palm.

“The Eye in the Palm of Kouranós, Lord Fate,” Sarrumos noted. He had little use for the gods, but his youthful tutors had literally beaten Their catechism into him.

“Yes, Kouranós—whose cult Hatteos revered over all others,” the vizier replied.

As the men examined the glyphs, two of the guards lit clay lamps. Once they had light, armed and armoured soldiers leading the way, they passed into the darkness.

None saw the flying, one-eyed creature that landed atop the temple lintel as the last of the crew passed through.

***

Flickering lamplight gleamed on awed faces, as they took in their surroundings. The shrine was a single, rectangular chamber whose roof was held aloft by a sea of intricately carved wooden pillars. A tiny pinpoint of light shown down from the center of the roof, directly upon a circular stone dais decorated with both familiar-seeming glyphs, including that of the tied serpents, and strange, twisting symbols whose significance was unclear, particular as unknown years of debris had drifted down from the hole above. Large amphorae and temple furnishings lay tumbled and broken about the shrine, thick with the dust of ages, though occasional wide tracks through the dust suggested something broader than a man and decidedly heavier, being dragged across the stones.

The vizier stepped forward then looked back at the others, clearly unsure what to do next. Ollad shook his head as if to say, I have done my part.

Clearing his throat, Lord Aranaro called out loudly:

“We seek the Guardian of Khalkûm.”

His voice echoed softly, but otherwise went unanswered. Nose twitching nervously, the vizier tried again:

“Great Guardian, we come from Tlawalko, heir to Hatteos’s fallen kingdom, and would have thy counsel.”

The mention of ‘Hatteos’ was answered by a deep hiss, that echoed through the shrine like a hundred pots boiling over at once. The hiss was followed by a loud, resonant rattle.

To seek is to search.

To search is to find.

To find is Destiny:

The solace of small minds

“Destiny, Great Guardian?” Aranaro asked.

Destiny is a pit,

That traps men all too soon

yet eager fools race to find it.

From Destiny wise men hide—or try,

Yet its marks all as clearly,

as morning sun brightens cloudless sky.

Despite the sing-song nature of the poor rhymes, the voice itself was sibilant, hissing like an autumn wind blowing through fallen leaves. There followed a sound of something heavy moving across the tiles beyond the dais, hidden among the many columns.

“Riddles!” Khossos said disgustedly, fidgeting with his sword hilt. “Great One,” the title sounded awkward on his lips, “if we’ve sailed all this way to listen to mumbled nonsense from some old crone who claims to speak with the gods—”

Though he had thus far seen little of the corsair to like, in this case Sarrumos agreed. Early in his exile he had sought out just such an old crone, and her ‘wisdom’ had proven to be no more real than her woman’s semblance, which had concealed an inhuman monstrosity. The memory made his throat dry and his skin clammy with sweat, and he realized with a start that his hand was on his sword hilt. With an effort of will, he let it drop to his side.

Khossos would have spoken further, but Aranaro held up his hand agitatedly, silencing him.

“We bring a token,” the vizier continued, his voice betraying nervousness as he held one of the jeweled amulets aloft. “From Khalkûm’s heirs in distant Tlawalko we bring a sign and ask the Guardian to look upon us with favor.”

The sunlight trickling in from the ceiling caught and refracted in the amulet’s massive, citrine, causing a blue-white radiance to flicker and glimmer about the chamber. The rattle sounded as an answering flicker of light replied from the temple depths.

Two eyes stolen,

brought now into the light,

conjoined to a third,

long hid from mortal sight.

“Yes, Mighty One,” Aranaro continued. “There are two amulets, and I have brought them both.”

Again, came the strange rattle and a flash of citrine light—gleaming now from somewhere off to their right. This time the sound of a great shape moving was less subtle, more hurried, the sound of old pottery grinding beneath some unknown bulk. A shadow, far larger than any mortal creature of Sarrumos’s ken, writhed and reared, then barreled forward. The young Naakali’s sword leapt to his hand, as he swung his aspis-shield down off his back. Ollad fit arrow to string, while the other armoured guardsman stepped before their master. Khossos drew his own blade with a loud curse but dropped back out of Sarrumos’s peripheral vision.

The shadow slowly coiled around the dais, like a noose tightening about a condemned man’s neck. As it revealed itself in the small beams of sunlight, they saw it was no creature of smoke and night, but a vast serpent, as large around as a tree trunk and easily the length of five tall men. Crystalline scales glowed like sparks of fire, a thick, bristling lion’s mane of coarse golden hair surrounding a long, wedge-shaped skull that sprouted stag’s antlers red as fresh blood. Most startling—and entrancing—was a bright, blazing diamond-like stone that gleamed from the center of the serpent’s forehead, which Sarrumos realized, with a start, shimmered with the same, citrine glow as the amulet the vizier held aloft.

Men bring me now my sister’s eyes

to taunt or to cajole

in any case, beneath my jaws to die!

The serpent reared, rising high over the astounded men, the gleaming stone in its forehead blazing to life, blinding them in its terrible radiance as the arm-length rattle at the end of its tail shook in anger.

“No, mighty olobit!” Ollad cried, stepping forward, hands held aloft. “Every tribe names the Wisdom Serpents in honor and fear! I am Ollad of the Hichitwa, of the line of Kun Uhwatsi, whom you aided may moons ago. I come now with these outlanders to make offering, not offense.”

The massive, antlered head swayed high above the homely archer, forked tongue flicking angrily. But then a deep, wheezing chuckle came out of the serpentine jaws, and the voice answered:

Spoken well, Uhwatsi’s child,

if only just in time.

We remember gifts freely given,

and do honor to your line.

“Does that mean it will help us?” Khossos asked in a hoarse whisper. The others ignored him, as Ollad bowed and gestured to the vizier.

“Mighty olobit, I come only as a guide, bringing this chief to you for counsel.”

Seeing his cue to speak, Aranaro straightened his shoulders and addressed the great serpent. “I ask the Guardian to forgive—I did not know that the origin of my forbearers’ ‘amulets’ and meant no offense thereby.”

The vast rattle on the serpent’s tail shook rapidly.

Three were we, egg-sisters, wise-ones all.

For our wisdom, Hatteos made us thralls.

Two freed by death, now there is but one.

Alone, through sisters’ blood compelled,

Hidden away from wind, and rain and sun.

The vizier listened, nodding. “And with these…eyes…Hatteos wrought a spell that bound you to this temple, and his service?” He was answered with a hiss and another agitated rattle.

“Yet Hatteos is gone, down into Tzatlokán many centuries ago.”

Foul lord to death has gone.

Yet here I remain.

This broken fane to haunt.

The simplicity of the answer was as chilling as the bitterness with which it was made.

“I like these ridiculous rhymes less and less,” Captain Khossos complained.

Once again, Sarrumos could not disagree. Then an idea came to him. Unfortunately, it meant he must try speaking to this strange being. He plunged headlong before he could talk himself out of it.

“Great Guardian of Khalkûm, I grieve for your loneliness! I too am alone; though whereas your world is small, mine is wide—yet the one place I most long to be is forever denied to me.”

The wide head, easily larger than that of a horse, swung to look at him, tilting to one side in curiosity, the glowing stone in its skull making Sarrumos avert his eyes as he spoke. “If there is a way to free you from this prison of stone, speak it, and we shall see it done!”

The arm-length rattle shook so furiously that the young Naakali was certain the creature was about to strike, but then its tail grew still, and the sibilant voice spoke:

What Hatteos’s false hands have stolen,

By his blood must freely be returned.

“So, if we give you the amulets, you will be set free?”

YES!!!

Sarrumos turned to the vizier.

“They are not mine to give, Great One, but if their purpose was to lead us here, then…”

“Yes,” Aranaro considered, nodding to himself. Then he turned to address the olobit. “Mighty Serpent, I am Aranaro, son of Drakomaxos, son of Tawanno. I am a vizier, not a king, but my line stretches back to Ekhinos, who was a prince of Khalkûm. By my lineage, I swear before all the Gods of the Six Courts that if you aid us now, I shall not step forth from this temple without seeing your sisters’ eyes returned to you.”

The great serpent seemed to consider these words, neck swaying, antlered head turning from side to side as it coiled so tightly about the dais that the stone began to crack. At last, it spoke:

Ekhinos!

Of ancient blood, and noble deeds.

If eggling swears by blood,

By blood shall we proceed.

Seeing the olobit satisfied, the men sighed and relaxed visibly. Aranaro, looking more confident, let the amulets fall back on his chest. “By my lineage and before the gods, I so swear these shall be yours, if you but share your wisdom.”

Speak.

“Mighty One,” the vizier continued, “We have come seeking a legend: the Fountain of Hatteos. Here I stand before one half of that legend made flesh—the Guardian of Khalkûm. Is the fabled Fountain real as well?”

The Spring of Eternity

Is real as the lives and deaths of men.

Beware the Font’s perversity,

For in both, it has oft played a hand.

“Spring of Eternity?” the vizier inquired. “This name is unknown to me.”

Treasure takes many forms.

Yet for mortals, meant to die,

Endless life is not the rose,

but only its bitter thorns.

“I do not understand—”

Look upon these ruins:

Monuments to folly and despair!

Eternity was Khalkûm’s greatest prize.

Yet where the sounds of life, of love,

of children floating upon the air?

“You are saying the Fountain, this ‘Spring of Eternity,’ destroyed them? Forgive my ignorance, Mighty Guardian, but I do not see how a fountain of healing and youth can kill anyone.”

What need have I to lie?

Destruction is not Death,

To perish is not

Of necessity to die.

Aranaro pondered that for a long moment, the unburned side of his face marked with confusion and concern at this ominous, if cryptic, information. “I shall remember. But where might the Fountain be found? Is it here in the city?”

Mortal man, the Fountain shall be found.

In this world, yet hidden underground.

Seek north by west to lands,

of waters brackish and cruel.

A scream of stone, carved by hands.

Well-hid from the eyes of fools.

“Back to riddles,” Khossos sighed.

“Underground? Is this a cave, with a natural pool or fountain, within?” Sarrumos wondered.

“What is a ‘scream of stone?’” Ollad asked.

But the serpent said no more.

The vizier pressed on, “Is the Fountain protected?”

The tail-rattle shook, a sound of broken branches and jangling bones, and Sarrumos swore the olobit laughed.

What all men seek,

only some men hold.

For such no havoc’s too great to wreak,

Few the seekers destined to grow old.

“I’m not sure that really answered the question,” Sarrumos complained. The olobit ignored him and continued:

No race is lost until it’s won,

A demon in gold and jade,

Close behind you comes.

In human form, but a soul of shade;

a most black and evil son.

“Kouras!” Aranaro gasped. “He hunts us still. Mighty Guardian, you have played me fair, and I shall fulfill my bargain. What must be done to set you free?”

Swear by blood and by blood shall we proceed.

“I think I understand.”

The vizier drew his bronze dagger, drawing it across the palm of his burned hand, wincing as the sharp metal passed through the thick scars and shiny, fire-wracked skin.

The horned-serpent’s rattle shook furiously, neck swaying in anticipation, the jewel in its skull growing lamp-bright as the blood stained its mates in the twin amulets, which began to glow in turn. The long neck leaned down, slit-pupiled eyes watching intently, eagerly—if a serpent could be said to show such emotions as eagerness or anticipation.

Wiping the knife on his bleeding palm, Aranaro sheathed it and then let the blood drip on first one amulet, then the next. “I, Aranaro, son of Drakomaxos, son of Tawanno, from the line of Ekhinos, Prince and First Spear of Khalkûm swear that what was offered has been taken, and what was stolen is now freely given in return. I return the eyes of your sisters, and before all the gods of the Six Courts set you free.”

Free!

The horned serpent’s voice rang out like a clarion, its echo booming through the shrine, making the man gasp and cover their ears.

Hatteos, betrayer and false friend,

Your spell is broken,

my bondage at an end.

The jewel in the olobit’s skull grew brighter, a second sun burning with a magnificent, terrible radiance, so that the men were forced to tear their eyes away, lest they be blinded as well as deafened. The wedge-shaped head reared back, jaws opening wide, and bellowed out that single word once more:

FREE!

This time, the booming shout drove several of the sailors and two of the soldiers to their knees. Ollad stumbled, doubled over, and Sarrumos staggered, certain something had ruptured in his ears. Oblivious, uncaring, head swaying in ecstasy, the olobit’s massive tail uncoiled from about the dais and lashed out, striking one of the many pillars and breaking it free of its moorings as easily as a man snapped a twig. Stone and dust rained down from the shrine’s ceiling.

“Careful, Mighty One!” Sarrumos cried. “I understand your joy, but—”

FREE!

The tail lashed out, shattering another pillar into wooden spears to tumble down among the endless shards of pottery. Soldiers threw up their shields and sailors their arms to protect themselves from falling stone and sharp spikes.

“We should go from here,” Ollad shouted. “Before—”

FREE!

With a speed that belied its massive size, the horned serpent uncoiled and struck out towards the shrine’s entrance just as its smaller cousins might strike at prey; the huge, serpentine body gliding across the space between dais and doorframe. The wide, antlered head was too wide for the door, yet undaunted, the olobit drove forward, shattering frame and lintel, an explosion of stone and dust billowing in its wake, as the roof began to shake and collapse.

“Take cover!” Sarrumos cried, pulling the vizier to the ground, throwing his aspis over them both. Sections of pillar and masonry broke free and came rolling down the stone steps into the sanctuary, one piece crushing a pair of sailors with a horrible wet sound. Ollad ducked behind the dais, pulling a startled Khossos down with him.

When the dust had settled, it was clear that the stone steps were completely, impossibly blocked by stone. A bronze greave, and the crushed leg that wore it, thrust out of the rubble.

“From their Destiny men will hide—or try,” Aranaro gasped as Sarrumos helped him to rise. They were both covered in a fine dust that made them seem like statues come to life, but otherwise were unharmed.

“And our destiny is to be buried alive!”

5. Entombed

“Everyone with a cape, a cloak or a belt—off with them!”

They’d spent a fruitless half hour desperately tearing at the rocks and rubble that entombed the entrance, and Sarrumos had had enough. “The sun hole above us is our way out of here, but we’ll be improvising our rope.”

“And how do we secure it?” Khossos demanded.

“We’ll need a spear—and some luck.”

“What do you intend?” asked the vizier.

“That hole is narrow, those of us with shields will need leave them behind, but I think we can all otherwise squirm through. That means a spear is longer than the hole is wide: if we can cast it through that hole so that it lies across the opening, the weight of men pulling on our ‘rope’ should hold it fast, while the first few of us climb out and help anchor the rest of us.”

Khossos’s expression turned as sour as curdled llama milk. “That’s a lot of ‘ifs.’”

“Perhaps. But there are no ‘ifs’—and no escape—trying to get through that rock pile. Now, let’s have your belt!”

The men began dropping shields and handing over belts and capes. Once the makeshift rope was ready and firmly affixed to the end of a guardsman’s spear, Sarrumos took it in hand, stepped back and cast. The spear easily flew through the opening to clatter on the roof above. The men cheered, but as he carefully drew on the rope, the spear slipped through the opening and tumbled back down inside the shrine.

Cursing, the young Naakali scooped it back up and tried again, with similar results. Khossos was already nay-saying. On the third cast the spear rolled horizontally across the opening and caught. Sarrumos tried resisting the urge to gloat, failed and gave the corsair captain a wide grin.

“It took a few tries, but still far less time wasted than we spent trying to move fallen stones, aye Captain Khossos?” Feeling satisfied at the flush spreading over the older man’s face, he let the matter drop.

Now came the vital test. Sarrumos pulled gently on the rope, then jerked it, carefully at first, then harder. Finally, he pulled with all his weight. The spear held. “Who’s first?”

“I reckon I’m the lightest!” one of the sailors said, stepping forward. Kicking off his sandals, he tugged on the rope and began his ascent.

He climbed swiftly for half the distance, then halted to catch his breath. The others held theirs as well, but the spear’s strong hickory shaft held. Letting his wind out in a long rush, the sailor began climbing again and was nearly to the top when Sarrumos noticed a movement just beyond the opening.

“Beware!”

The warning came as a winged figure, bird-like talons flashing in the sun, swooped down to attack the climber. Hearing the warning, the man looked about frantically. Seeing the owl-like monstrosity approach, he threw his one free hand up to ward his face.

The others, down below, had their first clear look at the new threat. Someone screamed.

In silhouette, the monster was an owl, if a large one. But its body was nothing more than a human head, with an owl’s feathers rather than hair, and wings in place of ears. From beneath the jaw were the expected short legs and taloned feet, but it was hard to look past that horrible face, which was itself a misshapen travesty of Prince Kouras himself.

The climbing sailor screamed as talons scratched into his flesh, and the makeshift rope began to swing dangerously, the sailor spiraling round and round, as he fought to hold on under the monstrosity’s repeated attacks, which tore away clothes and strips of flesh. A forked tongue darted at his face, and the skin sizzled. With a final scream, the man lost his grip and plunged headfirst, slamming into the raised dais with a horrible crunch.

Twang!

The moment the sailor began to plummet, his body no longer shielded his tormentor, and an arrow sank deep into the back of the flying head. With a hideous screech, the creature turned and spat, a think globule of some stinking, tar-like substance. Ollad threw himself to the side, the tiles pitting and steaming where he had stood.

Someone hurled a spear, but the winged nightmare evaded and let out another horrid cry. Now, the opening above them grew dark and then the air was filled with owls, circling, swooping, slashing at the men with their talons as their unholy master sought to escape. The soldiers crouched behind their shields; Sarrumos shocked at the force by which hollow-boned creatures no bigger than his head battered his aspis’s leather face, maddened with the desire to attack.

The homunculus with Kouras’s face had reached the opening and was apulling on the rope with its claws as it spat venom on the spear shaft to which it attached. There was another twang, and then a third, and two more shafts pierced it through. Tumbling over, it landed atop the dead sailor in a horrible parody of comradeship, its skin turned a dirty gray as it began to crumble.

Almost immediately, the owls ceased their assault and fled through the opening, whatever summons had called them broken. Still on one knee, Ollad had already put another shaft to string, and was scanning the ceiling above, but no other threats were to be seen.

“That’s twice now you’ve shot down one of Kouras’s monstrosities,” Sarrumos said.

Ollad shrugged as retrieved his arrows from the dust that had once been the sorcerer’s servitor. “Perhaps he should stop sending them.”

“In the meantime,” Lord Aranaro said, leaning on his cane, “this also means Kouras knows once again what we are about – and how to find the Fountain.”

Sarrumos looked to the sailor’s broken remains, then at the cloak-rope still hanging from the spear. “Then we’d best hurry. I’ll go first.” He gave the rope a tug to test his weight. Weakened by the monster’s venom, with a loud snap, the spear shaft shattered and fell to the floor beside him.

“I guess we’re digging,” he said ruefully, as he began removing his sword and shield. He looked at the broken spear and to the light streaming in from above and sighed. “Gods Below, but it would have worked, too.”

***

“Gaah!” Kouras cried, falling to his knees at the sudden pain stabbing straight through his heart. Although his ship lay at anchor downriver from Aranaro’s, he and his men were miles away in the deep forest, heading northwest, as he had heard and seen the Guardian advise the vizier through his servant’s eyes.

“What is it, Great One?” Surem asked.

“Nothing,” said Kouras, panting, though he knew what must have happened. Breathing hard, skin clammy, he stumbled to his feet. His chest still burned, but the sharp pain was fading. He looked with horror at the brown age spots forming on the back of his hands, the skin looking thin and lined like bark-paper. “Let us continue, time grows short.”

***

It took nearly a day before Aranaro’s expedition tunneled out the fallen stone. Exhausted, then camped that night on a hilltop, where the ground was less overgrown. From fourteen, they were only seven now. Realizing that Kouras must be close, Khossos had worried about a possible attack on his unsuspecting ship; as a pirate, attacking their means of transport home was exactly what he would do. After some discussion, including promises of greater payment in return for assurances that Khossos would wait for them, the corsair captain and his five remaining sailors headed back to the ship, while the men of Tlawalko followed the river northwest. Of the two killed in the temple, there was naught they could do but murmur prayers to Lord Death and leave them buried beneath the stone that had felled them.

One of the soldiers noticed the skulls first, when he headed down the hill a small way to relieve himself. Yellowed with age and impaled on sharp sticks, each had glyphs meticulously carved on the forehead. Aranaro studied the symbols, running his finger along the deep groves cut into the bone, and shook his head.

“Mysteries abound. The warning is clear, of course, but this,” he tapped one of the skulls, “is in Tehanu, or rather, a poor attempt at it. Many of the flourishes and details to the glyphs are either crude, or just wrong.”

“Your speaking-symbols are not a craft practiced in the north,” Ollad said. “Not among the Hichitwa, nor the Kato, nor the Nahez, nor any other tribe I know.”

“Then whomever set these here had some contact with Khalkûm and its people.” Sarrumos said.

“The city was abandoned almost a millennium ago,” the vizier replied, shaking his head, “These skulls are old, but not so old as that!”

“Can you read the marks?” Sarrumos asked. To him, the glyphs were reminiscent of the complex pictograms of High Naakal, but unintelligible.

“As I said, they are garbled, but the meaning is generally clear—they warn that to proceed is to invite death. Presumably, they wish to keep us from the Fountain. The real question is who set this warning out, and how do we slip past them?”

But there was no easy answer and camping on a hill just outside a boundary demarcated by dried skulls was still preferable to wandering in the night, so they reluctantly trudged back up to their camp, even though they had little hope of sleeping.

The skull-barrier was only a little less horrible in the daylight, and they all exchanged uneasy glances with each other as they stepped past it and headed down the hill back into the thick forest canopy. The countryside grew flat and wet as they passed into a wide bayou, aspens and hickory giving way to cypress, birch, and magnolia. Lord Aranaro ordered them all to remain alert for both watchers and evidence if, with their delay in escaping Khalkûm, Kouras was now ahead of them—but tracks were a difficult thing to find in wetlands.

Surely this was a land ‘of waters brackish and cruel,’ but where and what might a ‘scream of stone’ be?

Late in the afternoon, they had their answer.

They had splashed through the bayou seeing little more than the occasional spoonbill or heron, but the land had grown a bit drier as the river wound back into hill country. And while the hills themselves were small, unimpressive things, the portal that lay before them was not: an impressive, angry face—eyes bulging, brows curled menacingly, mouth open in a silent war cry—had been carved out of the hillside, which, stripped of its trees, proved to be made entirely of a strange, greenish stone that was neither jadeite, nor anything any of the men, including Ollad, recognized. Beside the opening was a massive stone, taller than a man, and made round by human hands. As they studied it, they saw it had been carved on one side to look like a tongue.

“Well,” Lord Aranaro chuckled, “I guess that leaves little room for doubt.”

Weapons at the ready, the men approached tentatively, expecting at any moment an ambush that did not come. The ground about both stone mouth and tongue was flat and muddy.

“The stone has only recently been rolled aside,” one of the guards noted.

“And not without conflict,” Ollad said, rising from where he crouched in the muddy path left by the great stone’s passage. He held up his fingers, which were wet with both bayou mud and blood.

“I suppose it was too much to hope we would arrive first,” the young Naakali captain grumbled.

“I prayed for as much,” the vizier said, leaning hard on his mahogany cane, taking slow, deep breaths. Like any highborn Naakali, who had been taught from childhood to endure suffering with stoic indifference, Aranaro had never complained, but the long walk through the bayou had clearly taken its toll on his endurance. “Now let us pray we are not too late.”

“That time is probably better spent preparing for what we will find within, Great One,” Sarrumos said testily.

“You doubt the gods?” one of the soldiers asked in horror.

“Doubt them? No. I am quite certain They exist, and care not at all about the desires of men. Let’s go.” And before any could make an answer, he stepped through the stone maw into whatever lay beyond.

6. The Spring of Eternity

The cave mouth opened into a shrine, no less impressive than what lay without. Twisting pillars made of the same, mysterious green stone held up an ornate ceiling covered in carved arabesques that wove in and around mysterious, human-seeming figures. The illustrations were obscured by their lofty height and the smoky, flickering light left by a single torch thrust into a verdigris-covered wall socket. The torch’s presence was further proof someone else had recently entered and was likely deep within and was thus of far more immediate concern.

A double-cube altar of black stone stood at the shrine’s far end. Just beyond stood a bronze goddess that was testimony to the long-dead metalsmith’s art. Eight feet tall, she was displayed naked but for a collection of necklaces, bracelets, and anklets, all depicted as fashioned from human remains. Her six hands wielded a wicked looking array of weapons—from lasso and net to sword and twin-tined fork. The goddess regarded them with unseeing eyes, fanged mouth open in an expression of mad ecstasy, bronze tongue licking sharp fangs. So lifelike where the goddess’s monstrous features, that the men half expected her to step down from her pedestal and attack.

“Kêrmoira, Lady of Dooms,” Aranaro explained. “A daughter of Lord Kouranós. Her cult has faded in recent generations.”

“A goddess of doom? I wonder whyever for,” Sarrumos said drolly, as he slipped the torch from its bracket. “There is an exit back here, into a tunnel of sorts…and steady drips of blood. Someone is wounded; badly, I’d say.”

The vizier nodded and gestured for the younger man to lead on. The passage was another cave, seemingly one unworked by human hands, and as it stretched away under the hill, they found themselves circling back on themselves until they settled upon a careful search for blood spatters, made elusive in in the flickering, crackling torchlight.

Eventually the cave settled into a single, winding “passage,” which in turn widened into a cylindrical chamber. The men no longer had to duck under stalactites, and Sarrumos was enjoying the freedom of walking normally when something crunched under his boot. Dreading what he would see, the young man looked down to find he had trod on a human skull. Holding his torch out before him, he scanned across the chamber, making out more skulls and neatly organized piles of human bones.

“Listen!” a guardsman whispered excitedly, “that’s the sound of rushing water. Aranaro-tzin, this race is yet to be lost!”

“It sounds like a waterfall,” Ollad said.

“Or a fountain,” the vizier added, barely controlling the excitement in his voice. They pressed forward, tracing a path carefully through the human bones, towards the noise of the water. Sarrumos stopped to examine the bodies. While some of the bones were rat-chewed or broken, and a few showed clear damage from weapons, their one defining trait was that they were burnt, scorched black where they were not merely yellowed with age, and laying in piles of greyish-white ash. Imagining the stink of using an underground chamber as a crematorium made his stomach convulse. He tried expressing his misgivings to the vizier, but Aranaro was impatient to press on, so Sarrumos abandoned the strange graveyard with a last glance back and took the lead, torch brandished high.

They entered a massive chamber, whose magnificence took their breath away. Daylight streamed in through two natural apertures, one high on the wall straight ahead, another in the rough-formed ceiling high above; together they provided enough illumination to reveal a circle of carefully worked and carved limestone cenotaphs that stood like silent sentries around—

“The Fountain of Hatteos!” Aranaro cried in wonderment and glee.

“The Spring of Eternity,” Sarrumos said more softly, overcome by the sounds and sights before him.

It was a natural pool, the water flowing up from some underground source; bubbling and jetting, sometimes spurting half again the height of a man, pushing upward from a central, raised cone of smooth limestone that pushed out of the pool’s center. The air was moist with water vapor, and had a feint, mineral scent.

“We are not alone, look!” Ollad hissed in warning, pointing towards a bent figure kneeling on the far side of the monolith-circle, head lowered, as if in prayer. A man’s body lay face down beside it, unmoving, three arrow shafts protruding from its torso.

Sarrumos might have mistaken the kneeling figure for one of the desiccated mummies found from time to time in Tehanuwak’s driest deserts and high mountain places, but peering more closely at the dead man, he recognized his stocky body and balding head: Surem, Kouras’s charioteer. Looking at the ‘mummy’ once more, he realized the truth and gasped in shock.

It was Prince Kouras; only a desiccated, horrifically aged version of the man. Hunched and shriveled in clothes that seemed far too large for his frail form, his long hair—what little remained of it—was as silvery-white as starlight, as was the thin beard that sprouted wispily from his chin. Hearing them speak, the prince’s haggard face looked up to regard the newcomers with hollowed, red-rimmed eyes. The pale cracked lips twisted into something that might have been meant as a smile but seemed more of a grimace.

“Aranaro! How kind of you to join me…but I could have used you sooner. As you see,” he gestured with a clawed hand to indicate his body, “my trip was not as simple as I had hoped. The savages who protect this place—the decayed descendants of fabled Khalkûm, if you can believe it!—were loath to let anyone in. They pursued us relentlessly, whittling my men down. Poor Surem here came so close, only to succumb at the end. You may thank me for clearing your way, even if the magical effort required has nearly killed me.”

“Consider your labors repayment for our bargaining with the olobit to find the path here,” Sarrumos said grimly.

The prince laughed; an ugly, rattling cackle that ended when he was forced to wipe away a bit of drool with one hand. “Ah, the Mongrel! I see you live, more’s the pity. You have repeatedly complicated my plans. I promise you an exquisitely awful death when I come into my kingdom. But first—”