THE DELIVERANCE OF BENRIMMON

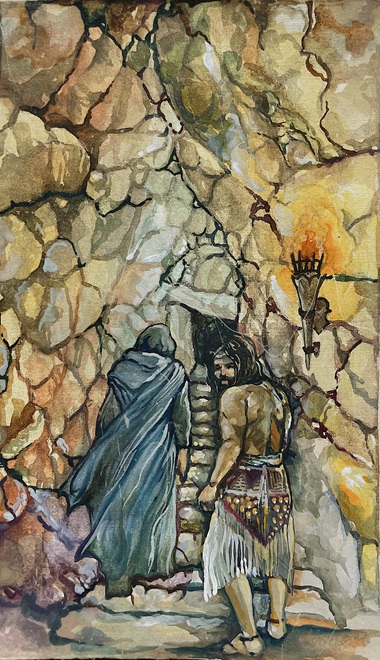

THE DELIVERANCE OF BENRIMMON, by Stephen Coney, art by Simon Walpole and Karolína Wellartová

This is the account of the deeds of Benrimmon, that my name be not forgotten, nor the great deliverance I wrought. It was the eighth year of Benadad, great king of the Well-Watered Land, when the gods set their mark upon me, Benrimmon, son of Shamash-Nuri, and chose me to be their champion. That is the year the earth shook and threw down the Tower of the Bull with the loss of seven stout warriors. A wind came from the direction of the rising sun, a scorching wind in place of the early rains which bring bounteous crops. Fish fell from a sky empty of clouds and rotted in our streets and fields. When we went forth in our chariots, the mighty host of the Well-Watered Land, to smite the Khamati, they were spared our wrath, for the night before battle, a great shadow rose up in the sky and swallowed the moon. Only the foolish would don armor and draw bow on such a day, after such an omen. The Khamati slunk, unsmitten, to their villages and we rode back, unarmored and without glory. It was a time of ill portent.

Ten days from the fall of the Tower of the Bull, I stood with my king in the City of Waters as the soothsayers sought again to discover which god we had angered, and what was the nature of our offense. The omens had been even more unfathomable than is their wont, such that even Shuri-nutal, priest of Attar, could find no clarity. Travelers said that it was the same in all the lands of men. Even the priests of the Gettiti, famed for the depth of their insight into the realm of the divine, could see nothing of sense.

They, too, read the signs as did our soothsayers. All the gods were angry, and that none were. It was a puzzling and dire time. I stood with the king in the company of the mighty, but could see little, for I was far from the places of honor. Though I had smote the Sons of Bit-Omri with a mighty arm, others had stolen my glory. I swear by Rimmon that it was my bow that struck down Naged-Habbayit. and not that of Adad-Yisi, the Foresworn.

We stood together at the place of divination, gathered around the altar under the burning light of the eye of Adad, our great lord and master, who rains down abundance. It stood directly overhead, an auspicious time for the penetration of mysteries, and it was the twelfth day of the month, a day of clarity. The altar of Adad is large, longer than a man, and is glazed the blue of Adad’s sky. It is a wonder to see and must surely be a place of revelation. The priests brought out the sheep, a ram three years old, the largest and the finest ever seen, and laid it on the altar, struggling vainly against its fate. A slash of iron ended the struggles and another opened its inward parts to examine its liver.

There were two livers. The sheep, this, the finest and most noble of rams, had two livers. It was without precedent and, furthermore, the fates they gave were opposite. All the gods were angry; none of the gods were angry. There would be great cataclysm; there would be a great deliverance. The message was chaos, even more chaotic than the arguing between priests, warriors, and counselors I rapidly left behind me as I made my way home. The talk, I knew, would be long, certainly well into the night as each strove to make himself heard. Now was the time for action, the chance for a man, a lone, mortal man, to seize glory. It might be a time for heroic deeds, a great deliverance. Why should it not be my hand to bring it?

My home then was the home of my birth and childhood, a smaller house far from the center of the city. It was a poor place for a woman as magnificent as is my wife and the strong little son and beautiful baby girl she had borne me. The only ones we had to serve the five of us (for my mother still lived), was an old woman and her son, a handsome lad, Temon, whom I love like my brother. I immediately sent him for my chariot, and ordered his mother to pack food, water and wine while I gathered my weapons, armor and a gift.

The Light of my Heart saw that I was determined upon some venture and, knowing from whence I had come, asked for news. I answered her briefly, my mind on other things.

“But where are you going my Husband? Why do you leave us at such a time?”

I heard the fear in her voice, and it pierced my heart. I turned and gathered my precious one in my arms. I would confide in her and her alone, for all know the proverb, “if three know, so does the world.”

“The soothsayers are blind, though no one yet accepts it. Perhaps the Magi, mighty in knowledge, can penetrate this mystery, but they are weeks away and the return journey is longer still. There is only one possibility that is within our grasp. I must seek out the Oracle of Bet-Shahan.”

I could see comprehension and agreement in her eyes, dark as night, deeper than the ocean, beautiful as the moon. She spoke.

“You are right, my Husband, for she is said to penetrate the deepest mysteries, when she can be understood. She is perhaps more famous for the obscurity of her pronouncements.”

“This is why none have thought of her as yet.”

“Yes, but they will.” She looked away and nodded, then whirled back. “But why must you be the one to go? And why right now? Why this day? The way is full of peril! Go back now and insist on this course. The King will send a troop if you but wait.”

“No. I must go. I must have the honor.”

“But you will have the honor of a wise counselor. Surely the King will give you a place in the troop that goes.” I could see fear in her eyes, fear for me.

“No. I would only travel with the group, in the back. Those on whose arms the king already leans would do the deed and bring the deliverance. Besides this, if we find the answer, I would be forgotten. Adad-Yisi would find a way to steal my honor yet again. But if nothing comes of the journey, all the shame would be mine. If I go alone, none will know if I fail. I sense that there is a great deed to be done and I must be the one to do it. I shall rise in the King’s favor and you and I shall have what we deserve.” It was an old subject between us, one that came up every time I went to war, and I knew what was coming next. She would tell me that I am enough, that we are not poor, that I need not risk my life. She is a wise woman but does not understand the fire that burns in a man’s heart.

However, my dear one surprised me. She simply looked me in the eye and I saw resignation there, resignation and acceptance. When she spoke, she did not address me by the familiar name used in the family, but the name by which I was spoken of in the city gates and which she used but rarely: “Benrimmon, you are a mighty warrior. Go, and do a mighty deed.” Her voice was steady as she said it, and I know it cost her something. Perhaps she does know the fire of my heart.

She removed her necklace and placed it in my hand, closing my fingers around it. “Wear this, all the blessing I have for you.” At first, I refused, for it was a powerful talisman of the Katiratu, personal goddesses of the women of her family, worn by her mother and grandmother before her. Between them, they had lost only two children in childbirth. But when I saw that she was determined, I steeled my heart, kissed her, and left.

I met Temon outside the gate. We mounted the chariot and were soon on our way, heading towards the mountains where the Oracle was said to live. I needed to move quickly, to go as far as I could before nightfall. For that is the end of the day and tomorrow was the dark of the moon, a day of ill-omen, a day for inactivity, for any task undertaken on such a day would be accompanied by bad fortune, and any deed begun on that day would be doomed to fail. This would serve to keep the king from dispatching his embassy to the Oracle, but it would not truly benefit us, for we, too, could not travel.

Consequently, we spent that night and day in the shadow of a rock, doing nothing, awaiting the blessed fall of night when we could act again. As soon as nightfall came and the unfortunate day ended, I was tempted to press on for a time, chafing at the delay. But Temon reminded me that we had not eaten, and it would be better for me to remain at my full strength, besides, it was a moonless night. How far would we get on such a black night? Surely the king’s men would not travel on such a dark night either.

We set out again as soon as it was light. I set a fast pace, for who knew if someone, perhaps even Adad-Yisi, had noticed my absence and divined my intentions? Perhaps he was trying pass me. I might have a rival even now. However, we saw no one from our city, only the occasional merchant or local. We wound our way out of the rich plains into the hills, buying food from villages, avoiding their settlements in the evenings, for, though we would be well-fed as honored guests, I did not have time for the hours of leisurely conversation it would require.

Finally, we were in the mountains, a place of rocks and trees. It made the warrior in me nervous to have my vision blocked to the right and to the left. We of the Well-watered Land fight on the plains, large fields of battle for large armies and great contests of kings. It is said that even before our fathers came to this land, mighty in deed, seized the City of Waters and slew its king, we had been men of the steppes.

Before we entered the mountains, I donned my armor, knowing that I had checked each strip of leather holding the metal in place, and that Temon kept the iron well-oiled. I did nor fear an attack from neck to knee for the strongest man cannot drive a spear through such plates. My helmet I also donned, tall, pointed, cheek-plates secure. I wore my sword, iron as long as my forearm, and sharp. My unstrung bow and spear I left in the chariot.

In this mountainous forest the road had turned into a track that was hard for wheeled vehicles. We were forced to walk, guiding the horses by hand. When the trail reached the crest of the mountain, Temon grasped my arm to stop me.

He whispered, “You should string your bow, my Father.” He always addressed me as father, since I am his master, though all knew that, in fact, he is my half-brother.

“Why? It is level and open here, finally.”

“But look ahead, my Father. On the way down, the trail skirts the side of the mountain. There is a cliff to the right and to the left rises steeply. If there is any place that is good for banditry, this is it.”

“They would be pretty poor bandits, in this country. Travelers are few.”

“But they need not be bandits, merely locals who care more for your goods than for your status as a potential guest. These mountains a poor source of food.”

He was right, of course, though I did not string my bow, at least not yet. Once we crossed the summit, the track quickly narrowed as it descended the other side, a cliff on the right and a steep slope up on the left. There was enough cover from shrubs and trees growing on the leftward slope to conceal a small party.

I scouted ahead alone. Waiting, as it were, to prove Temon right were indeed some bandits, four of them. They shot an arrow and charged. I care nothing for the arrows of such dogs. Its stone head shattered on my iron. As for the bandits themselves, they learned what it is to strive with a warrior of the Well-Watered Land, though I left them with scant time in which to apply their hard-won lesson. My shield shattered teeth; my sword severed limbs and exposed entrails to the light of the sun. One of them charged me with the courage and determination of a boar. He also shared that animal’s intelligence, for I am mighty not only in thew, but also in craft. I stepped aside. The sight of his wide eyes, flailing limbs and mouth open in a soundless scream as he plunged over the cliff lifted my spirits. At least his fellows perished to the sound of laughter. I could not have stopped myself if I had wanted to. What an oaf.

Soon, those who remained lay choking on blood or gaping at the ruin that remained of their bodies. I showed them that my blade is also one of mercy. Their spoil was poor, clubs, badly-made bows and arrows. One even carried a knife of bronze! The one item that was not like the others was a bronze helmet of ancient design. It resembled those I had seen on the walls of old temples of the Luvians, those peoples whom my fathers had subjugated. It had an uncanny feel to it, and I did not wish to touch it, for it was a holy thing. Its presence roused my curiosity about these bandits.

I knew they must have a lair and went looking for it. I soon found it, a smallish cave they had expanded and tried to make comfortable. The poverty of their goods rendered them even more pathetic. They clearly slept together for warmth, sharing two blankets, one threadbare, which would hardly have covered them all. There were some embers in a broken pot which they nursed through the day until cooking time, probably so as not to give away their location with smoke. Wood for the fire was the one good they had in plenty. They had some stale bread, which I took, but most of their bread they had soaking in a small vat of water, trying to make beer. It wasn’t yet ready and I left it.

Overall, the cave appeared as unrewarding as were the bandits themselves, but the presence of the helmet prompted me to persevere and it paid off. In a dark back corner, some cut reeds and staves were leaning against the wall. Behind them was an arrow unlike any I had ever seen. It looked to be made of a single, scarlet feather, though what bird could have produced such a feather I fear to think. It was longer than my arm, and had clearly been cut down to that size. The feathery parts had been carefully trimmed from the shaft for most of the length, leaving some at the end like normal fletching. The head appeared to be made of black stone but was unlike any I’d ever seen. The whole arrow, save the fletching, was covered in tiny writing. What’s more, when I was examining the writing, I brought it near my armor and the head leapt to my iron and clung there. It was obviously an article of great mystical power. I had never heard of its like in tale or song.

I would have spent my life wondering as to how such men had such an article, but there was also a clay tablet in Luvic, which my father had insisted I learn, gods bless him. It had been taken from a messenger from the temple of Runtiya in Adana. He carried an unnamed artifact which had been saved from the ruin of the great Empire, fallen in the far north long before my people had come to the Well-Watered Land. Their god had ordered it dispatched to the Oracle for no specified reason. That was all.

It was fairly clear that this messenger had fallen afoul of these bandits, poor fools. Normally, the gods protect such holy messengers from all threats, and even if the god is distracted, as Runtiya clearly had been, the status of holy messenger, which I presume the helmet proclaimed, should have saved him from importunity. No wonder the bandits were so poor at their trade. Not only were they fools, they were fools cursed by a god. My hewing had been holy work.

Temon and I laid the three out on the open area at the summit where he had been waiting. Stones were there to build a cairn and protect them from beasts. It would not do for their kin to find their bodies mauled and dishonored. Though clumsy and cursed by a god, they are nonetheless men, and were possessed of a foolishness which at least resembled courage. As for the other, if his kin find him not at the base of the cliff, he will be the food of vultures. No doubt such a one has an equally stupid wife somewhere who will remember to mourn him for a week before she begins making eyes at other men. I left the spoil, save the arrow and helmet, to be found as well. The helmet I did not wish to touch, so Temon wrapped it in a cloth and laid it in the chariot. The arrow I did not fear, for I had already touched it without consequence.

We continued on, having lost precious time ridding the world of idiots. I had hoped to arrive at the Oracle before nightfall, but it was not to be, thanks to the bumpkins. It was the next day when we finally saw a trail leading off from the main path. Next to it was a stone carved with a single, large eye, the sign we sought. Unfortunately, the trail was too steep for the chariot and horses, so I had to leave Temon behind with them. Divested of armor and weapons, I went up barefoot, carrying only my gift as a supplicant and the red arrow. It was an urn of the beautiful kind that comes from over the sea, filled with my best olive oil. I had received it as a prize from the king and it was the finest thing I owned. The whiteness was so white, the black so black; the secret of its making is not known to our potters. Ours are not so smooth, nor gleam as do these. As for the helmet, I wore it, wrapped in the cloth, for I could not carry both it and the urn.

The way was arduous, mainly because I was barefoot and didn’t have the use of my hands since I was carrying my offering and the arrow. It was also a serious time. At the top, I would discover if my mission was a vain waste of our most precious possession, or if a great deed awaited me. On top of all this, the helmet made me nervous.

The trail led to a cluster of buildings around a cave. Save for one fine house, the buildings were small and poor, the cave dark and ominous. A trickle of smoke was rising out of it. The place was shaded and silent; there were no sounds of birds or even insects. The only sound came from an old woman who was poking at a fire and looked my way as I approached.

She spoke in the croaking voice of the old. “Ah, another who seeks to know something best left unknown.”

“Surely you have seen the dire portents,” I replied, “And would know the cause of such things yourself.”

“I always find out whether I wish to or not, and have already heard,” she answered. “For I hear all the oracle says. Still, most of what I’ve heard through my long years I wish I did not know, and so do most who have come here.”

I didn’t like this kind of talk, but I expected it. Holy men are always vague and speak in circles when answering queries. But if there was ever a time when I needed clear direction, it was now. I wanted to move past her as quickly as possible, both to hear the Oracle and to rid myself of the helmet, but I didn’t like this statement that she had already heard the Oracle speak on this question.

“Have others come before me?” I asked, “Have they sought to know the cause of these happenings?”

“You think you are the first? Ha!” Normally, such a laugh would provoke my anger, but hers did not feel directed at me, rather at something else, perhaps life or the world. So, I waited and she continued, “Men of the Khamati have already come as well as some from the houses of Agusi and Adini.” She looked me over, “You, I believe, are from the Well-Watered Land?”

“Yes,” my voice shook, for I was dismayed to hear that I was not the first.

She saw what was in my heart and snorted, “So, if there is a deed to be done, you wish to be the one to do it? This deed is one that is perhaps better for another to do. The cost will be heavy.”

“I will pay any cost.”

“Really? Before you know it?”

I thought of my wife and her contentment with our lot. “I would not pay with my life or that of any member of my family.”

“That, at least, shows some wisdom, though why a man with such insight would go on such a foolish venture as this is not clear to me. You do not look to be a stupid man.”

My anger flared and I didn’t know what to say so I asked, “Are you a priestess?” Just in case she was.

She grunted and said, “I am the lowest of the low, a drudge.” She suddenly looked up and pointed an arthritic finger, “But still holy and sacrosanct!” I think she feared I would beat her for her insult, but that is not the kind of man I am. Besides, she reminded me of my grandmother. Still, I did not wish to lose any more time.

“Then how may I speak to the Oracle?”

She simply pointed at the cave and said, “Stand outside and call.” She turned back to the fire and added, “leave the helmet here, and the other.”

I did as I was told, leaving both helmet and arrow. Standing as a supplicant, I called a query into the cave. To my surprise the answer came from behind me. A man in fine new robes was coming out of one of the houses, a priest. He was businesslike and simply took my offering from my hand. He examined it with a critical eye, grunted, opened it, tasted the oil, and grunted again. Without a word he returned to his house with the urn. A moment later he came back and gestured me into the cave.

It was a foul place, not very deep, but black with the smoke of years. Lit by a small fire, it reeked of smoke, urine and dung. In the back was the Oracle, a small, skinny figure, squatting against the wall, tearing some cloth that appeared to be the scraps of a blanket. The ground was strewn with other bits of cloth as well as old reeds, rotting food and human waste. When we drew near, she whirled and eyed us suspiciously from under her tangled mass of filthy hair as she struggled to tear her blanket into smaller pieces. I could see that she was a teenage girl, chained to the wall with iron. She was completely naked, but was so filthy and streaked with excrement she could never be an object of desire. She was repulsive, but I sensed that she was just the vessel for something larger and greater. Obviously, the Knowing One which lives within her does not permit her any comforts. The honor of being the vessel for the divine would seem to outweigh any outward suffering, at least that is the idea if anyone thinks to care about her.

I will not describe the ceremony the priest performed when he asked my questions. It was all of a piece with what I’d seen countless times at home. When he had asked what must be done to appease the gods, the girl hurled herself on the ground and raved, thrashing around and babbling nonsense. I was stunned, though I had heard of this kind of prophecy, of course. The priest had been watching me with a bemused expression. If he expected dismay or surprise from me, he was disappointed. It does not do for a mighty warrior to show such weakness.

He began his interpretation, which I knew would be a riddle of great difficulty, “Sun rises; sun sets…” Then he froze, for a chill had entered the room, had entered and seized our hearts, our souls.

The girl stopped raving and thrashing. She stood and seemed to grow, though her body remained the same. It was as if I shrunk in her presence until I was but a worm. The priest was on the ground next to me, groveling and banging his forehead on the stone floor. I found I had knelt, head bowed to the ground.

The Oracle now spoke in a clear voice. “That is enough of toying with people using riddles and games. Three have already sought direction, that they might bring deliverance, and been sent away in darkness and ignorance, only one able even to discern the correct direction to travel. This is a time of portent, a dire time and now one for amusement. Listen well. There has come into the world a mighty worm from the chaos beyond creation. It is even now destroying all order and stability. A champion may slay it, if he wields a spear whose iron head has been soaked in the blood of a laasa. Travel one day towards the rising sun until you come to a cave on your left. There you will encounter a laasa to slay. Do so and soak your spearhead in its blood. Not far from there, in the direction of the rising sun, is a pillar and a larger cave. Before you enter and battle the worm, bathe in the spring, then go slay the leviathan. He who does so will be blessed by all the gods, beloved. Now go!”

She turned to the priest, “Give this message to all who come, lest this one should fail. Your mouthpiece will not speak for a time, while we decide in council what to do with this spirit who used such a time for its own pleasure.” With that, the girl collapsed, whether in a faint or in death, I do not know, for I raced from the cave.

Outside, the old lady cackled when I emerged. “Another who is swifter to leave than to enter.”

“Make no sport of me, Crone.”

“I do make sport, I admit. It is the last pleasure left to me, since I lost my last pair of teeth.” She opened her mouth to display gums, bare of teeth save a few nubs, none of which were close enough to work together. “No toothsome meat for me. But wait!” she held up a finger, “You will be glad you listened.” I could not afford to reject any knowledge, so I grunted and remained.

“Long have I been here, since before I had even fifteen years. Much have I seen; much have I heard. I have heard the gods promise much. I have sometimes seen them give. I have often seen them take. I have never seen them give without taking still more. They are not generous; they do not love us. They need us, you see, these petty gods, and they hate it.”

At my look, she laughed again, “What? You are offended at my impiety? I am forbidden to them. Soon, I will be out of their grasp anyway, in that place where they will all one day go.” Clearly, she was wanting to shock me. I resented her because it worked, and I could not keep the surprise from my face. Who wishes to be the butt of a joke, especially that of an old woman and a stranger? “Yes, the gods, too, will go the way of all flesh. It has been decreed. They did not make this world; they found it. To discover its origins, you must look deeper.” She paused, squinting at me speculatively. “I sense that you will penetrate these mysteries one day, but not today. I’ve said enough.” She returned to poking the fire as if I were not there at all.

“That’s it?” I asked, incredulous. “You said I would be glad I listened!”

She looked up in surprise. “That wasn’t enough? You want instruction like a child? The point is to be wary of gifts from the gods. If you are their blessed and beloved, you will pay your share for it. Few find their way out of such ‘blessings.’ Whether you will or not is clouded to me. I would council you to leave this deed to another.” She returned to the fire.

My heart felt a soothing presence as she spoke and some part of me recognized it as divine, though very different from what I’d felt in the cave, so I asked, “Are you a mouthpiece for the gods?”

She didn’t look up. “That was my sister, long ago. We were given as an offering to the Oracle together and they chose her to be the mouthpiece when next one was needed. I was to follow her, for the time such girls live is short. In the scant year before she died, I found a way to be disqualified, and to be a mouthpiece for another.” After this riddle, she refused to say any more until I turned to go, when she said, “Take the arrow. It is meant for you, I think.” The arrow remained where I had lain it. The helmet was gone. I took it and left for Temon and my chariot.

Temon was dismayed when I reported the deed I must do, especially that I must slay a laasa, one of the man-headed, winged lions that guard us from demons and evil. “If slaying a laasa is but a small part of this task, how great is this worm?” he wondered, and I secretly agreed, but said nothing. “And laasa are the servants of the gods. Why would they send one of their faithful servants to be killed?”

“Gods always demand sacrifice; this is but a piece with it.”

“And why must a man fight this thing? Surely this is a task for a god. Does not Adad boast that he is the slayer of such enemies?”

“Be quiet, Temon!”

“I only wish to ask, my Father, how the gods can aid you if they are powerless to fight such a beast?”

That was enough impious talk, and I told him so.

Temon and I took that path toward the rising sun, as the gods instructed. It was indeed a day’s travel when the narrow track opened out to a grassy, open space. To the left, the mountains rose and there was a cave. I knew it was the correct cave because in the open ground before it were the bodies of three warriors, smashed, bloody and unspoiled. It was the work of a beast, not a man, for what man would leave such rich prizes? Even rent and bloody, the armor and weapons were worth much. At least one of the three groups must have puzzled out the Oracle’s riddle, at least enough to come to the cave. These, then, must be either men of the Khamati, the Agusi, or the Adini. From what I could see of their gear, I would guess them to be of the Agusi.

This was not a sight to give a man’s heart courage, for the Agusi are not weak men, but what could a warrior do? I donned my own armor and weapons and went forth to face a dire foe. Temon urged me to bring my bow. I pointed out that the instruction had been to bathe my spear in the blood of the laasa, but he insisted. His advice is often good, so I carried the bow and arrows and left them just outside what I considered to be the battleground, the place of the contest.

Shield on my left, spear in my right, I advanced on the cave, shouting a challenge in the name of Adad, the benevolent and mighty, god of my people. My steps brought me closer and closer until finally a form emerged from the mouth of the cave.

It was the laasa. Its face, noble and bearded, looked down at me without expression. Its lion’s body was the height of a large man, such as myself. It rustled its great wings. It was magnificent. It was immense. It was terrifying, and I must slay it.

Accordingly, I leapt forward, thrusting at its breast, hoping for a quick injury to tip the scales. It was ready and danced aside, nimble as a colt. It launched itself at me just as fast, but hadn’t gathered itself, so it was not hard to dodge aside.

When it landed, I immediately thrust at its side with my spear, but it sidestepped and I dealt it only a glancing blow which did no injury. It swatted at me while I was overbalanced, but it was also in an awkward position and did me little hurt. Thus, the battle raged between us, back and forth, neither able to get the upper hand until, through clever footwork, I positioned myself for the blink of an eye at its forequarters, and, both feet planted, perfectly balanced, I thrust behind its foreleg with all my strength.

Nothing happened. The spear didn’t even prick the skin. Not a drop of blood was spilled. The laasa grunted and whirled again, knocking me sprawling on my back, something under me, my spear lost. I was stunned in both mind and body. With skin impervious to my weapons, how could I defeat this beast and complete my mighty deed?

Even now the mighty being rushed upon me to end my life before it ever mattered. I rolled and saw that I had fallen onto my bow and arrows. There, perfectly to hand, was the red arrow that I had taken from the bandit. I grasped, turned and thrust upward. The laasa, pouncing at me, hurled itself upon the point. The arrow was indeed an uncanny thing, a transcendent thing. It pierced the hide of the laasa like papyrus and continued into the body. My enemy froze and threw its head back. A wail tore from its throat, piercing and human, as I thrust the arrow deeper. I thrust until only the fletching showed. I scrambled to get up and away as it collapsed. It lay there, living but breathing heavily and seeming unable to move. It was not what I expected. A creature of that size should have had a lot of fight left in it after only a single wound. However, I was not about to question a gift from the gods.

I found my spear and tried to thrust it into the wound, but it would not enter. In any case, it turned out not to be necessary. Blood issued from the wound and bathed the sharp iron of the head. Instead of running onto the ground, it disappeared as if it were entering the metal, like water pouring onto dry cloth. As I watched, the head grew in size, extending. I held it in place until the head was as long as my forearm, then the blood started to run off it onto the ground. Three drops fell off the blade and the flow of blood stopped.

I grasped the end of the arrow to retrieve it, but this elicited a growl from the laasa, which, alarmingly, was still alive. Gone the high-pitched wail, this was the growl of a lion. Deciding that such a creature could keep the arrow if it so wished, I turned and ran.

Temon had been watching with the horses ready. I leapt to the back of the chariot and we flew together from the field of my triumph. I did not look back at the body of the magnificent foe I had perhaps slain.

The god had spoken truly, for it was not far before we came to the cave of the leviathan. The greenery had disappeared and what little had ever lived in the place was dead. The trees were desiccated and shrunken, also mostly fallen. Where there should have been scrubby bushes, there were only dead tufts, the grass, like the leaves, had disappeared entirely. The area outside the cave looked to never have had much life anyway. It was rocky, with a huge outcropping of stone in the middle of the open space in front of the cave, the pillar, I suppose. The cave entrance itself was immense, higher than a tree.

The area in front of the cave was uncanny, strange, unholy. Nothing was as it should be. Rain fell, then it was so hot the air shimmered, then it snowed, there were gusts of wind, blasts of water, and pebbles falling upward. Plants shot up, changed shape, emerged from thin air, disappeared, changed into animals who melted into cold, dancing fire. Then it would stop for a time, then resume. Nothing was stable. Nothing was orderly. I can see why the gods were sparing in what they said. Temon pointed out that since the gods owe their power to their ability to understand and manipulate reality and fate, something purely chaotic would be outside their control. He often spends too much time thinking about impractical matters beyond his ken. He reasoned that the gods can do nothing against such a thing. The most they could do is to send one of their angels to be slain by their champion. We would see if said champion would share the angel’s fate.

As the god had also said, there was indeed a spring right as the trail reached the area of the cave. It was not what I expected, for it was not a spring of water, but bitumen. It oozed out of a rock in an undulating rivulet, filling a small pool. I stripped out of my armor, for it would avail me nothing against such as beast as I was to face. I laid aside everything and entered the pool mother-naked. The bitumen was slippery and treacherous, but I immersed myself in it completely and arose, dripping with the favor of the gods. After cleaning my palms thoroughly, I donned my loincloth and my talisman, took up my spear and advanced on my destiny. I did not look back.

The chaos emerged rhythmically. Temon guessed that it was the breath of the beast, poisonous to the very fabric of the world. I waited for a break when the thing inhaled and rushed forward. If I was caught by the breath, the divine ointment I wore protected me and I made it through into the cave and saw the beast. I froze, for it was a serpent, fortunately sleeping, and one so large that every man and beast I will ever see in my whole life would, together, weigh less than this vile thing. It was not quite large enough to encircle the City of Waters, but it was longer than it and it weighed more than all the buildings and walls combined. The chaos faded away in a small zone around it. It is understandable that the beast would not inflict its chaos on itself, for then it would not be able to maintain a form that could engender the chaos. I moved into the stable zone and took stock.

Against such a beast, my great king and all his armies and all the armies of his vassal kings and allied kings would have no hope. Indeed, we, along with all the foes we have ever faced, would simply perish as the great serpent rolled over us. What was a single man to do? I could but try.

Accordingly, I advanced and began my climb to the obvious target, an eye. The scales were rough and enormous, two arm spans, and they provided an easy climb. My spear had a leather loop at the end so I could sling it and reduce it to a minor irritation rather than the major impediment it would have been otherwise.

It felt like a day, but it was probably not really very long before I came up to the eye. It was the size of a house and covered by an imposing lid. Seeing no reason for preliminaries, I braced my feet, put the tip of my spear at the line where the eyelid met the face, tried to wiggle it into the crack and then I thrust will all my weight.

It had no effect. It was like the laasa’s hide again. Not even a spearhead soaked in angel blood did anything. I pressed and strained, but still nothing. In frustration, I pulled the spear back and thrust it at the eyelid, over and over. It bounced off, skidded off, and bounced off again. This, at least, appeared to have some effect, for the serpent huffed in its sleep. Encouraged, I tried to pry the lid open again. Still nothing, still nothing…then it opened, revealing an immense, vile eye, an eye larger than a city gate. I lost not a moment and thrust with all my strength, but again my spear bounced off. The creature had a second eyelid that it could see through. The eye looked around, having felt something, but not much. However, I was so small and so far on the side, it didn’t see me. It closed the eye and shifted a little as it went back to sleep.

What was for it a small movement was, for me, an earthquake. It’s fortunate that I still wore the spear’s loop, or I would have lost it. I flailed and slid down the shifting surface. Being certain that I was about to fall from a great height, I was gratified to feel my foot find purchase. Blindly, I clung until the tremor passed and took stock. I was now in the serpent’s ear, large as a cave. Spear close to my side, I stepped in.

It was not a cave, of course. It was roughly round and the floor and walls were smooth. There was no wax such as we have in our ears. Instead, there were insects the size of my hand, round, many-legged, vile. They mostly ignored me, but one bit my foot. It was painful and I crushed it under my heel. It took a surprising amount of my weight before the body collapsed into a sticky mass.

I tried to ignore these disgusting things as I made my way through the darkness, one hand against the wall to steady myself. The beast started shifting again. No doubt its ear tickled. I came to hairs, some thick as my finger, others fine like spider webs, sticky and coated with dust and pebbles. I slashed them and they fell before my iron like wheat. I pressed on, deeper, until I came to the end. There was a skin stretched from floor to ceiling. I could not go around it and so I slashed it, too. The ground shook and I lost my footing. This time I was not wearing the loop and so I dropped my spear. Fortunately, the passage was small, so it was not hard to find. I stepped through the shredded skin and into the chamber beyond. Here it became very small and I crouched and crawled forward like a child, my speak beneath me. The shaking continued.

I made my way as deep as I could into the beast on the assumption that the deeper I went, the closer I was to the vitals. When I could crawl no further, I placed the tip of the spear against the side of the passage and pressed. With a crack the blade pierced the skin and entered the serpent. The ground shook more violently, though in a passage so small, it was impossible to fall. I pressed on, feeding the spear deeper and deeper into the beast’s head. The motions changed, I could sense that the serpent was moving, probably leaving the cave. The spear met resistance; I braced both hands and pressed. It suddenly yielded. The motion was more violent now. I was bucking up and down, like in a chariot over rough ground, but, of course, I was encased in the tube on the vile ear, and so suffered no bruising.

I fed the spear deeper and deeper until I came to the end, the rest having passed into the beast. I grasped the rounded back of the shaft, braced my back against the passage and pushed further. It slid deeper. My arm passed out of the ear canal and into the beast’s flesh. When I was almost at my arm’s full extension inside the serpent, I hit another obstruction and something else happened at the same time.

I felt something I have not since I was a small boy and my father would toss me up as a game. I could sense that I was rising in the air, rapidly. I could not see it, but one’s body knows when it is flying upward, higher than I had ever been. The leviathan must be raising its head into the sky. Certain I was going to die when we returned to earth, I used the last of my strength to push against the obstruction before death claimed me. It yielded to the laasa-infused iron, my arm thrust into the beast up to my shoulder, and the spear left my grasp. There was a torrent of hot, burning liquid. It welled up my arm and burst out into the ear, bathing my side where I lay. It was a burning agony everywhere it touched my body. The agony was to be short lived for, at the same time we began our descent. Faster and faster, I felt us plunge and then I knew nothing.

I awoke in a dark, unfamiliar place. I struggled, confined, and then it all came back to me. I must get out of the vile tunnel. I wormed my way back, panicking. Something was different. Something was wrong. There was no air. The only air was that which was trapped in a pocket around my head, arms and chest. I crawled backwards as best I could, but the walls of the tunnel pressed against me, impeding me. I passed the shredded skin and my worst fears were realized. The ear canal had lost its rigidity and collapsed. If I didn’t get out quickly the little air I had would grow stale and I would die.

I fought my way out, battling against the walls that sought to keep me in, the bitumen eased my passage for a time, but then it was gone, left behind. I fought on. Insects bit me. It mattered not. My loincloth untied and came free. I felt it against my back, my neck, my head, and it was gone. I cared not. In fact, it gave me some assurance that I was indeed making progress. It was taking too long. I was panting, the little of pocket of air I was bringing with me no longer fresh. My head felt light and I started to see lights. I was certain that I was soon to meet my father in the grey, dusty land of Mot when my feet broke free into cool air. With renewed strength I used the last of my energy to wriggle until I got a knee out, then it was a simple matter to pull myself free.

I fell, for the beast was large. Fortuitously, the head had rolled such that the ear was not far from the ground, no more than the height of my house, else I would have broken bones. As it was, I lay on my back gasping in wonderful, sweet, cool air. When my lightheadedness was just beginning to pass, I laughed. I laughed and laughed like a madman. This made he lightheaded again which brought it to a stop. I arose and saw that I was outside the cave, as I had surmised. I strode back to Temon, mother-naked save for the talisman my dear wife had given me

Temon was waiting and helped me to the gods’ spring. The bitumen had disappeared. Now it flowed with clear, wonderful water. I plunged in, knowing it would not remove the bitumen, but it would at least clean off the beast’s blood. As I cleaned myself Temon told me that the serpent had come out of its lair shaking its head and then it began to hammer the side of its head against the great outcropping of rock we had seen. It grew more frantic and finally had lifted itself up to an astounding height and plunged down, smashing itself against the stone. There was a tremendous crack and it moved never again.

This certainly explained what I had felt from the inside. When Temon finished, I told him what I had done and experienced inside the beast. He was amazed, and when I spoke of my battle to get out, he pointed out that had my wife not given me her talisman, I would not have lived. The Katiratu being goddesses of safe birth.

The water, miraculous as it was, cleaned the bitumen, which was itself also of divine origin, so I need not have been surprised. Bruised and battered, we turned to home.

Before we had gone far there was an itching in my arm and side, deep in, like the sensation was coming from my bones. I tried to scratch, which availed me nothing, but then it subsided and was replaced by pain, slowly rising from my bone through my muscle. It was unwelcome, but I could do nothing about it. It kept getting closer and closer to the surface until, like bubbles bursting, a flakey whiteness broke out on my skin. My whole arm and part of my side became crusty and white. Temon was a picture of alarm for my sake and a suppressed fear. Should he flee this disease? I knew he did not wish to leave me, and would not. However, I knew what this was.

“Fear not, Temon,” I assured him. “This marks the places where I touched the gore of the serpent. No one will catch this.” For I knew this to be true. “Perhaps a god will cure it, since I am their champion.” I certainly hoped so.

Temon was silent for a time before he said, reluctantly, “The gods could do nothing against this beast…I fear…”

“You fear that this is beyond their power.”

Even more reluctantly he answered, “Yes. Yes, I do.”

I thought on this and concluded that he was right. “Then it is a mark of my victory.” I straightened up. “Yes, yes, it is. It is the mark of my victory, of the gods’ favor.” I looked again at my arm and its hideous affliction and wondered if some oil would lessen the intensity of the gods’ favor.

We did not return to the Oracle. I wanted nothing of the crone and her haunting words. In fact, we took a more direct route home, travelling in settled lands. That we we could avail ourselves of hospitality on our victorious return trip. Though I wished to be home quickly, we were out of supplies. The hospitality was good, as expected, save for two things. First, three villages refused us hospitality on account of my affliction. I cursed them, their crops, their cattle and their offspring in the name of the gods for rejecting their deliverer because of the mark of divine favor. One of the three repented at my words and gave us a grudging meal and place to sleep. The second fact that marred our return was that even in those places which offered hospitality, none wished to eat of a loaf that I had touched. Even having heard our tale, they feared the mark.

I arrived at the City of Waters at midday and went directly to the king, though it pained me to not see my wife. It was she with whom I most wished to share the victory, but to go home first would be an insult to my monarch. Kings are kings. The reception I received was great, everything a man can hope for from his king.

The soothsayers and priests had foretold my coming and the success of my deed was already known, though the tale was not. The great king Benadad, my king, awaited me along with the noblest of the land. He clothed me with purple and put a crown on my head. He wrapped my hand and arm with the finest linen, to hide my affliction, for the gods had spoken of that as well. I rode with my king in his own chariot. Knowing how Adad-Yisi had been yapping at the heels of my fame, he had that foresworn cur lead us on a circuit within the city. Thrice did we circle from the Palace, to the House of Attar, to the Gate of the Sun, and back. The people thronged the streets, showering us with glory, the king and Benrimmon, on whose arm he leaned. I, I Benrimmon received this glory, for it was I who had done this deed.

After the third circuit, we repaired to the banquet hall where the feast appropriate to a deliverance such as mine was laid out. There, at last, I saw the Light of my Heart. She was dressed in purple, and heavy gold encircled her throat. She reclined with the queen. They laughed and shared dainties together.

I reclined at the high table with the highest in the land among whose company I now numbered. With the king I shared meat and we drank from the same cup. From that day the king leaned on my arm and when the armies of the Well-Watered Land went forth to conquer, Benrimmon led them. Adad-Yisi ate at the lowest place for a short time. I did not see him slink away, but he was soon gone. Neither he nor his sons attained to glory in my day. Had he not lied and stolen my fame I would not have begrudged him a place of honor in our hosts, though his father and mine had been bitter rivals, but what he did, he did.

It was long before we returned home, but return we did. The family had heard the news from Temon. They waited for me, save the children, for it was late. I kissed the sleeping treasures, my dear mother, and finally my precious wife, though in different manners. In all this I was eager to be alone with my dear wife. As I sat with the king, heavy with honor, all of my ambitions realized, I had not eyes for them. But my eyes often drifted across to the most beautiful woman in the room, save, of course, the queen, the flower among thorns, grace in human form, my heart. I longed to share this moment with she who is half my soul.

When I finally stood alone before the Light of my Heart, I removed the talisman and placed it back around her neck. “Your blessing saved my life. Without it, I would surely have perished. This great deliverance for our people is your victory as much as mine. You are the root of my strength. From now, I will stand at the king’s right hand and you will live in a house worthy of you and will have a girl to comb your beautiful hair.” With my wrapped hand I reached up and stroked it. She took that hand, kissed it and gently unwrapped the linen, exposing my affliction. I flinched back, but my strength, though mighty enough to strike down the enemies of the gods, was as nothing in her soft hands. She gently kissed each of my fingers and placed my hand on the smooth skin of her neck. I longed to pull her to me and kiss her, but the sight of my horrible skin against her perfection paralyzed me.

She saw my hesitation and said, “It’s fine, my love. I’m proud of you and am glad you have achieved your ambition. I love you no matter what you do or what you look like.” She reached up and stroked my hand.

“It is the sign of my victory.” I said it with a bit too much force, for I wanted her to see it as an honor, as I strove to do.

“Oh, Naaman, don’t hide behind bravado with me. It bothers you; I know it does. Together we will seek a deliverance for you from this, but until then, and always, I love you.”

She melted my heart, this lovely little woman. I gathered her in my arms and we kissed. I remembered again that she was why I had sought this honor in the first place.

“Well, perhaps you are right, but it will not change the fact that we will live in a magnificent house and you will have a girl to comb your magnificent hair.”

She smiled up at me and said with a grin, “Well, even though I didn’t want you to go, I won’t complain to have a girl to do my hair.”

I laughed and stroked her hair myself, though my hand itched.

This concludes the story of the Deliverance of Benrimmon, son of Shamash-Nuri. As for the rest of the rest of his great deeds, how he rode his chariot over the corpses of the sons of Bit-Omri and how he seized the crown of the king of Amat and placed it on his king’s head, and how he was delivered from his leprosy, are they not written in the chronicles of the Kings of the Well-Watered Land?

________________________________________

Though Stephen Coney has lived in Croatia, England and the Russian Far East, and has spent most of the twenty-first century outside the United States, he now lives, reads and writes in Dayton, Ohio.

Simon Walpole has been drawing for as long as he can remember and is fortunate to spend his freetime working as an illustrator. He primarily use pencils, pens and markers and use a bit of digital for tweaking. As well as doing interior illustrations for various publishing formats he has also drawn a lot of maps for novels. his work can be found at his website HandDrawnHeroes.

Karolína Wellartová is a Czech artist, painter creating images predominantly with the wildlife themes, nature studies and the literary characters. She’s mostly inspired by the curious shapes and a materials from the nature, but the main source still comes from literature.

From a young age she tried to express herself and her observations on paper. Painting and drawing were always the most important thing for her and visiting the local art school helped her understand the new techniques and the science of the colour mediums. She’s the award winning artist for “Best Book Cover in 2015” in Czechia.

Her work has been published in American magazines such as Spirituality Health Magazine, International Wolf, Metaphorosis, Orion, and Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. Check out more of her work at her website.