SUFFER THE WITCH

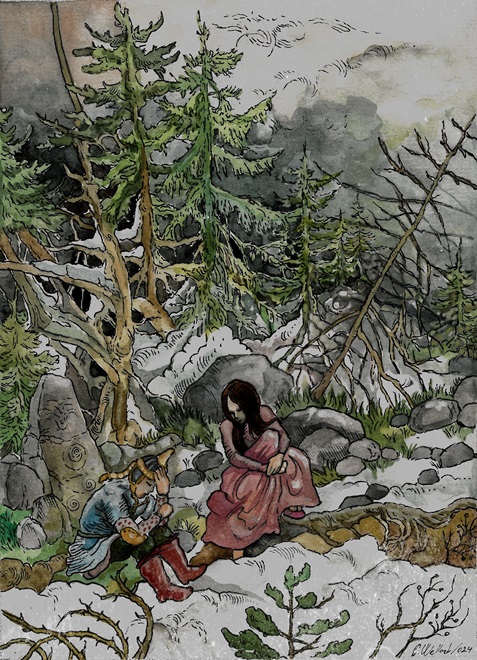

SUFFER THE WITCH, by Joe Kelly, Artwork by Karolína Wellartová

His brother’s blood and brains splashed across the floor as he fell, the short-bladed hacking sword clattering away from the nerveless hand that would wield it no more. Colla gaped in shock and horror, his own gory blade hanging in a limp fist.

He looked up, shaking his head; and all about him the other O’Briens Dubh answered with a stunned silence that swift was fermenting into vengeful hatred. His father Ferghal’s eyes seethed a deadly fury. For Colla should not be alive. That was not how a proper story would have gone. Fair Colla was the younger brother, the weaker: unmanly, cowardly, fearful and jealous of the broad-shouldered, dark-eyed Rónán, the mighty warrior, one worthy of the old Clan epithet of Dubh.

But a single panicked swing at Rónán’s bellow of rage, and Colla’s blade had cleaved Rónán’s skull and sent him crashing dead to the floor of the family house. His arming sword, the one he’d just been gifted, with the O’Brien battle cry inscribed upon the deep, broad fuller, would never know the sweet taste of a foe’s blood.

Colla gabbed silently. He tried to say, it was an accident–I didn’t mean to kill him! Name o’ the Morrígan, ever since they were boys, he’d lost every fight with Rónán, be it with blunt blade or fist and teeth! How was he to know, the one time it mattered, that Rónán would fail to meet his blow?

But the Black O’Briens had no sympathy or pity for him. The wrong brother had died.

Slowly, Ferghal rose, his huge, hairy, rangy bulk filling Colla’s vision. He bared his teeth and hissed, “Kinslayer!” And he gripped the hilt of his giant, broad-bladed sword.

Colla panicked. He didn’t want to fight his family, least of all his father–no matter how much they hated him, Colla still loved them–

He cried in terror, and with the flat of his sword he dashed the hearthfire in the middle of the room. All about men shouted as the sparks and embers flew. Colla whirled and smashed head-first through the closed window. The shutters tore his scalp open; lights danced before his eyes. He hit the frozen ground with a pained gasp and a stumble. Sick and half-blinded by the braining, Colla sprinted, winged by terror and grief, one hand clenched about the searing head wound that soaked his hair with blood, the other still grasping his arming sword.

Behind him the great door was thrown wide, and with bloodcurdling cries of vengeance the O’Briens Dubh followed him. In but fifty strides, Colla reached the dense and unyielding wood that ringed his home. The heathen sons of Black Turlogh were a clan of outcasts and outlaws; their homesteads were all hidden deep in the most savage and ancient wilds of Eire, far from the reach of the Norman interlopers and the prying eyes of the slaves to the Pallid Christ. All the Black O’Briens were at home in those wilds; but Fair Colla, the loner, the little one, was even moreso than his cousins.

Still, it took a very long time to lose them, for they were winged by vengeful bloodlust. Colla never knew when or how he escaped his family. He only knew that, when at last he collapsed, exhausted and half-frozen, it was dark, and he was alone.

He lay there a while; and when at last his legs steadied enough for him to stand, he rose, and made his way still deeper into the winter-rimed wild.

#

Colla was cold. Colder than he’d ever been in his life.

On through that silent wilderness he trudged, no longer knowing or caring where he went. Tangled bare boughs, dead brush, ice-slicked rocks, brown turf, gray skies, cruel biting nights: all blended together with the aching numb, the silence, the winter stillness. All were an endless procession of painful sensations that meant nothing to him anymore.

He fell to his knees, then slumped into a fetal crouch, unable to go any further, and long past caring, for he had no reason to live.

He should have let Rónán kill him.

Blearily he looked up. Something, some blind impulse, had drawn him to this spot over the past few days. The conscious part of him, the man-part, had curled up and shriveled away from the hunger, the weariness, the pain; but the animal in his soul had led him dumb and thoughtless on, seeking only survival. And something had attracted the attention of that scared and savage animal in him.

There, squatting sullen above him: a stone. A dwarfish menhir. A relic of the age when the Aes Sídhe walked the upper earth.

He peered closer at it; and what he saw, would have made him shudder, were he not frozen beyond even shivering. It was no relic of the Aes Sídhe, after all. It was a thing of their ancient enemies, the children of the Fomóire: the Cruima Sídhe. The Children of the Grave. Its unclean lines squirmed wormlike over the worn and lichen-encrusted surface. Its form was vaguely manlike; but it had no face–or nothing he recognized as such.

He stared at it a while; and in his delirium he thought he could feel it speaking to him. Of a time before time. Of a race that was never human, yet once had almost been; a race that was raised up to replace the dying embers of the ape-people when that foul race was almost driven to extinction. But then the ape-people had returned, and they had taken from the Children the new land they had been given by the Gods. They had driven them underground, to hide in the shadows and the dark places.

He blinked dumbly. A bleary shadow was approaching him, through the dead winter woods… one of the Children. Its boneless body moved like a man; but it was no human. A strange blood flowed in its veins; a dark and alien soul burned in its breast. A soul for dark times, a soul to live on when the Old Gods departed the Earth, and the light of life and magic died, and the cold wind of the void swept over all the land–

A cold hand touched his shoulder.

Colla leaped from delirium back to wakefulness. He flailed about, grasping for his sword with numb and useless hands.

The girl jerked back in fright. “I thought you were dead! You did not answer when I called…”

Colla looked blankly at her. He sagged back down again. He muttered something; he knew not what. The girl’s words, he had barely understood.

Her expression turned to alarm. “You’re dying! Come–my home is near.” Futilely she tried to lift him; but Colla could not rise. His will was gone.

Desperately she shook his shoulders. “You’ve got to move!” she said, “the blood is freezing in your veins!”

He looked up at her; and at last his vision seemed to clear. By the Morrígan… she was beautiful. Weakly, he nodded, and whispered “Aye.”

Somehow, he staggered to his feet; and, leaning upon the girl who grunted and strained beneath his weight, he began to walk.

#

Her face haunted his fevered dreams. Sometimes it was beautiful; sometimes hideous. Atimes, it was not human.

When at last he fully woke, he was glad to see it was beautiful after all. He smiled feebly.

She saw his eyes, clear at last, and she smiled back, and brought him warm broth. When his throat was wetted, he asked, “Did I thank you yet?”

She sniffed a little laugh. “You hardly knew where you were. You were lucid enough to talk at times, but it was like talking to a man in a dream.”

“Well, then.” He took another deep sip of the broth; he felt weak, but awake, and hungry. It meant he was healing swiftly, blessed be the Gods. “I’d like to thank you. And to ask your name.”

“Sadb.” She was of the kind who is beautiful even without perfume and jewelry. Dark hair, shaggy but clean, like her hut, which was well-kept for all its rudeness. Her livid brown eyes seemed to read Colla’s soul.

Colla lifted himself with an effort. The windows were shut against the cold, but just without he could hear the subtle sounds of the deep wild, the crackling of the icy branches, the occasional shuffle or thump of falling snow, or a half-frozen creature seeking winter sustenance.

“Why live so far out here?” At once he regretted the blunt question. He lay back down, and smiled his apology. “Or if you’d rather not say…”

“I don’t mind.” Sadb was still smiling. It was enchanting, that smile. “I’m unwelcome among my people. The feeling is mutual, believe me.”

He looked about the hut. Dried herbs, mortar-and-pestles, grotesque things floating in pickling jars. He nodded. “You’re a Christian? And your family didn’t like you being a cunning-woman–am I right?”

Sadb hesitated; a darkness dampened her smile. “You’re half right. I’m a Christian, but my folk didn’t object to my craft. Everyone has need of a healer atimes. But I had not enough hatred for our enemies, and so I was mistrusted, and cast out.”

Colla snorted; his smile grew rueful. “The Irish have enough enemies already. Clan brawls with clan, Christian and Pagan cut each other’s throats. And now the damned Normans come to reive and plunder, and seize what of Eire’s not already been burned or slaughtered or stolen by the cursed Norse… I’m sick to death of killing.”

Sadb bit her lip, considering him with those piercing brown eyes. “Well,” she said at last, “you may stay here, if you wish. Not much company,” she added with a smile, “but no fighting or killing either.”

Colla looked back into her eyes. Somehow, he felt he could trust her. Wishful thinking, perhaps, but the feeling was strong, and good. He nodded. “I wouldn’t mind sleeping on your floor atime.”

Sadb replied with an honest surprise in her eyes: “You don’t want the company of my bed?”

Colla gaped at her. “Your bed!”

Hastily, she added, “That is, if you’re more comfortable–”

“No!” His laugh was awkward. “Oh, I’d be glad to take up your offer! Only, you hardly know me–I hardly know you. We’ve only now just talked.”

“You forget, Colla–we talked aplenty when you were still half-awake. I already know your name, you see? I know a few things about you. Enough to trust you, I think.”

Colla tried to smile back; but he felt his face turning red. “To be honest… I’m surprised you’d take to one like me.”

Her smile fell, and her eyes grew yet more piercing. “Like you, how?”

“Weak. Unmanly.” Colla snorted ruefully. “I’m a whelp. The runt of my family.”

“And you think I care?” Sadb’s smile returned. “You think I’ll be dreaming of some mighty-thewed Pagan warrior to sweep me from my feet, and save me from your unworthy embrace? Come now, Colla. We’re alone out here, and you’re man enough for me. And we both desire peace. Why not find peace together?”

And Colla smiled broadly; and he answered, “Why not?”

#

They spent a time together, that winter, and they found peace.

Came a day, when Colla returned from a foraging, singing as he tramped through the still frozen forest. Sadb peeked from the hut, smiling at him, asking with her piercing eyes, what are you up to?

By way of an answer he held up the two big rabbits. “Stringy bastards,” he said, “But meat’s meat, eh?” He laughed giddily as he swept into the hut and thumped the dead rabbits upon the table. Ah, he could already taste the rabbit in the stew. So happy was he, that he said without thinking: “I praise ye, Morrígan, oh mother of my clan!”

He grabbed a butchering knife–but he stopped at the shadowed look in Sadb’s eyes. “What?” he asked.

She shook her head; but her reassuring smile was false. As were the little words with which she tried to soothe things: “’Tis nothing. Come, let’s clean those rabbits.”

“Sadb.” He stopped her with the name. She did not meet his eyes. “What’s wrong?”

“All’s well, Colla.”

But Colla shook his head. “I won’t let it fester.”

She nodded, and sighed; and the words tumbled out of her in a rush: “I wish you wouldn’t cling to the Morrígan.”

Colla murmured, “I thought we agreed to let that be.”

When Sadb looked up, the intensity in her eyes took him aback a little. “Colla, what if the Morrígan isn’t what you think her to be? What if she’s not the kind and benevolent goddess you believe?”

Colla felt a rush of anger. He snapped, “And what the hell has your kind and benevolent Pallid Christ done for you lately?”

There was a silence in the hut, chill as the winter without.

Colla’s surge of anger ebbed to shame at his harshness. More gently now, he said, “Look, we’re both outcasts; we’re both ill marked by fate. But that doesn’t mean we have to blame each other’s Gods, call them demons or some such.”

Sadb began, “I’m not blaming your Morrígan–”

“Well, then, what? Why be so upset over an oath that means nothing to you?”

Again, that intense look crept into her eyes–desperation, Colla realized. “I’m worried for you, Colla,” she answered. “I’m thinking of your soul.”

“Oh, come now.”

“I’m serious! Colla, it’s worse than you realize! The Morrígan–”

“That’s enough.” Colla did not raise his voice; but its flinty quiet made her fall silent at once. “Sadb,” he said, “leave it be. I stayed with you because I sought peace. I don’t want us to start fighting over our Gods.”

Sadb’s eyes grew tender; and that struck him deeper by far than her look of worry. “I’m sorry, Colla. I’m trying to leave it…”

A pained silence settled again within the hut.

And then a sound without broke it: the sharp crack of a dry and frozen branch beneath a foot-tread.

Their eyes flashed to the door, then to each other. The sound could mean only one thing; for the deep woods where Sadb made her home were accursed, haunted by malevolent spirits and bogies. Not even the Norman lords, with their retainers armored as glittering beetles, dared them–least of all, in the dead of winter.

Colla grabbed a boar spear, and gingerly he cracked the door and peered out.

Six men they were. Bandits. Shaggy, filthy, heavily built, faces made ugly from the scars of fisticuffs and knives. Two of them supported one who could not walk by himself; his head hung limp and he wheezed with a terrific and crippling agony.

The one who led them was a great, shaggy bear of a man. Colla grimaced; for he reminded him of the worst parts of his father. Big, brawny, hairy, brutish. Only the outlaw captain had not Ferghal’s sharp, clever eyes; and he was shorter, hairier, much fatter: a dimwitted bully who threw his weight around.

With one thick hand the big outlaw leaned heavily upon a stout walking shillelagh; his breath came in great panting gusts of steam. His other hand rested upon the crudely whittled hilt of a long-bladed fighting knife. He took a deep breath, and bellowed, “We seek the witch of these woods!”

Sadb was at Colla’s shoulder before he could warn her to keep out of sight. The big man spied her. “Witch!” The shout fell dead amid the still winter wood. “I need your help. Heal my brother here!”

The two brought the staggering one forth. Sadb hissed in sharp horror; for his stomach was wrapped in blood-drenched rags.

She shook her head emphatically. “I can’t heal such a wound!” she said, “I’m just a cunning woman. He needs a surgeon, or a priest!”

But the shaggy bear of a bandit growled, “You’ll heal my brother, or you and that scrawny boy of yours will know ten times his pain. Understand?” He grinned a rictus grin of menace. “Now you save him!”

Colla wrung his hands about the haft of the boar spear, uncertain. He could hold them at the door atime. But they would hack their way through the thatch roof. And once inside, these vicious wolves of men would have no mercy.

Sadb’s gentle hand upon his shoulder decided for him. She needed not say a word. He nodded, and set the spear aside.

“Good lad.” The beefy outlaw took his hand from the knife hilt, and he started for the hut. “You’ve nothing to fear from us, as long as my brother lives.” He gave Colla and Sadb his ugly mirthless grin once more as he trudged into the hut. The other bandits followed in his wake, the big man’s brother whimpering and wheezing still, the rest glaring–but not at Colla. Him, they spared only contemptuous glances. Their nervous and dangerous glares were for Sadb.

She cleared the table hastily and threw a hide over it, and gestured to the two carrying the dying brother. Gingerly they laid him upon the crude surgery table as she hurried about the now-crowded hut, fetching a bag of herbs here, a bottle of some strange distilled stuff there. As she set the things on the table by the dying bandit, she told them: “I’ll do what I can. But as I said, I’m but a cunning woman. I can’t do much more than ease his suffering a time. His only hope is a surgeon, and soon–and a lot of luck.”

The bearish bandit sneered, baring miscolored and decaying teeth. He shook his head as she went to work. “Nay, witch. You’ll not see us off so easily. We know damn well who you are, what you can do. You’ve power in your blood–you consort with demons by moonlight!”

Colla growled, “Watch your mouth.” The big bandit turned menacing eyes on him, and Colla quailed, but somehow the anger kept the tremor of fear from his voice: “Whatever you may think of her, Sadb’s a good woman, and a good Christian.”

The bandit’s menace turned to disbelief. With a cackling laugh, incongruously high-pitched for his size, he said, “What lies has the witch been filling your ears with, boy? Her name’s not Sadb–it’s Scáthach! And she’s no more a Christian than I’m an honest man!”

Colla’s stomach sank of a sudden. He wanted to tell the big ugly bastard off. But it was as though the rosy veils of hot love were suddenly lifted. By Lugh’s long arm–when had he ever seen her pray? He’d thought she was being understanding, not forcing the nailed god of Rome upon him… but had he ever even seen a cross in her home?

He opened his mouth to ask, who is Sadb–Scáthach? What do you know of her?

He never got the chance.

With a bloodcurdling scream the stricken bandit leaped up from the table. Every muscle in his body bulged and knotted. His eyes were swollen to bursting with blood, popping out of the sockets. There was an insane, an animal, fury in them.

The others turned to him in wordless shock, even as he yanked a dagger from one of his companions and plunged it to the hilt in the man’s heart. Colla gaped as the other bandits screamed in horror.

Sadb grabbed him and shoved against the wall of the hut, shouting in his ear, “Keep away from him! Don’t look at him!” She buried her face in his chest, and with one flailing hand she tried to turn his eyes. But Colla could not look away. He stared on, sickened with the gore and the horror, as the crazed bandit ripped the dagger through the stricken man’s belly and, blood and entrails flying in an arc, he swung round and slashed another bandit’s throat to the bone.

The bearish leader howled his own wordless agony. He threw one huge arm round his own brother and, as the other fought bestial against him, he drew his own dagger and began plunging it into his beloved brother’s side. The remaining two stabbed his gut and slashed at his face and neck with their own crude blades; and the three of them butchered their own friend and brother who was turned into a mad animal before their very eyes.

It was over in moments. It seemed a gory eternity. The hut was splashed sanguine and stank of hot blood and ruptured innards. Abruptly, the shapeless, bloody travesty stopped fighting back, and slumped lifeless in his brother’s arms. The hairy brute of a man sobbed openly and crumpled to the floor with the corpse. The other two stared with stupid horror at the dead man in his arms.

In another moment, they would realize what happened. They would be mad with fury; their vengeance would be awful. Colla had no choice.

He threw Sadb off him and leaped to the door, to the boar spear still leaning by it. One of the bandits’ eyes lit afresh as he saw was Colla was doing. With a cry he tried to bat the spear aside, but Colla’s thrust was true. He caught the man in the stomach, and with a horrible wheezing gasp he collapsed.

With a fresh cry of pain and fury the sobbing leader leaped up and threw his thick arms round Colla. The spear was pinned to Colla’s side, the tip still stuck in the other man. They thrashed about the hut, the big bandit roaring insanely as he tried to crush the life out of Colla, the other man gasping and wailing as he clawed at the spear being yanked about in his mortal wound. The spear haft crushed Colla’s ribs, threatened to break them, but it was all that kept the brute from fully wrapping his strength round Colla and squeezing the life out of him. The remaining bandit stood stupid with horror, his quivering mouth agape, his dagger forgotten in a hand nerveless with paralytic fear.

At last the big bandit threw Colla with a roar. He smashed into the table and fell prone to the floor. His head swam; he was half-blinded by the rush of blood. Something thudded by his head–the butchering knife, its point a finger’s length from impaling him.

He grabbed it without thinking, even as the big bandit dropped down and straddled him, vengeance and murder in his eyes. His thick hands went to Colla’s throat, and he squeezed and squeezed, and the blood swelled within Colla’s brain. Colla fought back, wild and blind, without thought, without reason, driven only by the basal desperation to live. Time and sense disappeared beneath those killing paws. There was only the maddening helplessness, the animal instinct to escape. He felt his skull would burst. His throat would break and collapse any moment. All that remained was the dying pain, rising to a breaking crescendo.

And then, the hold loosened. Colla’s vision returned, and with it a semblance of human thought. He saw the eyes of the big man glazing with mortal agony. Only the dying glow of the murderous hate kept them open. And he saw, too, he was stabbing with the butchering knife–had been stabbing it, the whole time, again and again into the big belly, until the whole lower half of the bandit’s trunk was a gore-spilling mass of torn flesh.

He kept stabbing. The blood and bile splashed and flowed down his arm and over his chest; the hilt of the knife grew slick in his hand, threatened to slide down and slice his fingers off. But he kept stabbing.

With a final gurgle the huge bandit’s eyes went blank, and he slumped dead atop Colla.

He struggled beneath the lifeless weight. Feet and palms slipping on the blood and the bile, he gasped and hissed as he pulled himself slowly from under the bulky corpse. He looked up–the last bandit was staring at him with the stupid and terrified eyes of a deer caught in a meadow.

Colla thrashed his legs from beneath the corpse and staggered to his feet. The whole time, he was thinking, the man will wake from his stupor, he’ll fall upon me with a cry and cut me before I can defend myself. But the bandit stood still, shaking a little, his eyes blank.

So, with a grim look in his eyes, Colla advanced on him with the butchering knife.

And, like the deer in the meadow, the man abruptly turned and ran.

Colla staggered after him. He slipped on the gore and fell sprawling in the threshold. Awkwardly, painfully, he staggered back up, groped for the long knife in the snow with numbing hands slicked by gore and bile. By the time he was back on his feet, the bandit had a bad head start. Colla rasped a curse, and followed.

He followed, through rime-brittle woods that cracked beneath his feet and his thrashing limbs. The bandit was no stranger to the wilds himself–it was a struggle, and Colla could hear him gasping and wheezing with desperate fear as he thrashed through the wood; but somehow, for the better part of an hour, the bastard stayed ahead of him.

Colla kept thinking, I’ve got to catch him. He can’t keep it up. Even a whelp of his clan, Colla was a Black O’Brien, a master of the wilds, a hunter and a killer at heart. This Christian bandit, this cur, didn’t stand a chance.

But then, the bandit crested a ridge ahead of him; and he stopped, just for a moment, and screamed “HEEELP!”

Colla froze a moment himself. The bandit scrambled over the ridge, and Colla shook off his paralysis and followed. As he reached the ridge, the bandit was half-running, half-falling down the far side of the ridge, waving frantically and hollering so that his cries echoed off the far side of the nameless wild valley.

And in the hollow of the valley, Colla saw smoke. And by the campfire, the figures of men, half-screened by the brush. They were standing, peering into the woods–calling back now, waving.

Colla swore again; and, panting and half-frozen, he turned back.

#

Colla swayed on his feet as he stumbled back into the hut. For all Sadb’s efforts to clean them, the smell of the bodily fluids still spun his head. His whole body, everything around him, was drenched in an stomach-churning slurry of sweat and hot blood and stomach bile and death-piss. It was the smell of a battle, a smell Colla had never wanted burning his nostrils again.

Abruptly fury welled up within him. He whirled on Sadb–no. On Scáthach. She was looking at him expectantly–had he killed the last man?

Instead, Colla shouted, “What the fuck was that?! What happened to that man?!”

“Colla…” She shook her head, her creased with strain. “What happened? Did you kill him?”

“Damn it, Sadb!” Silently he begged the Gods for the patience to keep him from strangling her. “Scáthach. The big bastard called you Scáthach. Why?”

“Colla, please! Did you–”

He waved her off furiously. “He got away! Found some woodsmen and called for help.”

Sadb’s eyes bulged with terror. Without another word she began dashing about the hut, grabbing things and throwing them into a satchel.

Colla shook his head. “Have you gone mad? Sadb…” No response. She just kept up her frantic packing. Colla hissed through clenched teeth. “Scáthach. Is that your name? Answer me!”

“Damn you, Colla!” She turned on him with the desperate fury of a cornered animal in her eyes. “We haven’t time for this! I promise, I’ll explain all, but now we’ve got to run. We’ve got to flee, because you let that man go, and he’ll tell those woodsman, he’ll tell everyone he can, what he saw! People will hear his story–they’ll seek us out! They’ll come to kill us!”

Colla nodded. “So you’re not an innocent cunning woman. You are a fell witch. A consort of the dark powers–”

“Colla, listen to me!” But he answered her pleading eyes with silence, anger and mistrust; and so her expression grew cold and closed as well. “Fine,” she said. “You can be angry with me. You deserve to be. But we’ve got to run, both of us. Because they’ll hunt you down and kill you, just as surely as they will me. And I can’t watch you hung because of…”

Her face cracked. She turned away abruptly, tried to hide her eyes; but he could see the tears in them.

He nodded. Fine, then. The cold anger did not leave his eyes; but he began to pack, as she had asked. He would follow her a little while longer, if only because he had nowhere else to turn.

But, he told himself, he would not forget her lies. And he had to wonder, now, just what it was she had said to him–done to him–in his fever; and why it was, that he had felt so sure, upon awakening, that he could trust her.

#

The deep winter woods were deathly cold and silent. In the darkness of night, in the frigid quiet, one could believe there were no living thing for miles.

Colla watched over Scáthach as she slept. He watched, he tried to tell himself, to keep them safe; but he fooled himself not. Of course there was nothing to fear out here. He stared at her, because his anger with her smoldered still. And it smoldered because… the Morrígan deliver him from it, he still loved her. Be he bewitched or no, he couldn’t deny she had treated him with kindness, with tenderness. Nor could he deny her beauty, or the way in which her look entranced him still.

Damn her, he thought.

Her eyes snapped open. She drew breath with a hiss. Another moment, and she was sitting up, fear in her eyes as she looked at him. “We’ve got to run. They’ve found our trail–they’ll find us!”

More questions. How could she know? He glared silently at her a moment, then rose to swiftly pack their kit.

As he stamped out the smoldering coals, he muttered, “Not even my clan would try tracking the deep wood at night. And the O’Briens Black are the best woodsmen in all of Eire.”

Scáthach hefted her pack. “Trust me, they’re coming.” And she was off, agile as a deer amid the dark wood, so that even Colla struggled to keep up.

He glanced back when he could, tried to listen. Nothing. Not a sign of anyone or anything else. Which didn’t mean they were not followed: his clansmen might have come within three strides of their camp before Colla had the barest chance of knowing they were there. But in the middle of winter, in the dead of night? Even they couldn’t track and sneak so swift. Not at the rate Scáthach was going.

Loud as he dared, Colla hissed, “Scáthach?” She jerked back at the sound, and glared at him reproachfully. But he asked on: “Where are we headed? You might tell me that, at least.”

Her eyes flickered away from his. She whispered, “You’ll see when we get there.” And she made to march on.

But Colla was having none of it. With a quick stride he grabbed her arm and pulled her to a halt, and he said, “No. No more lies. No more putting it off. You’ll tell me now, who you are.”

She gasped, “Colla, you’re hurting me!”

“Tell me!” There was menace in his eyes; but it was born of fear, of frustration. Of the grinding gears of painful love.

Still, though he hurt her, though he frightened her as he never had before, she did not speak.

And he felt the pain of what he did, reflected in her eyes. He released her. She did not start off right away. He could see she wanted to tell him things. Things he already guessed. But she feared what would happen when she did.

Instead, she could only say, “Just… trust me a little longer, Colla. Please. Once we’re free of our pursuers, I’ll tell you all. But not yet.”

He sighed. “Will you swear it? Will you swear on your God, your Gods, whatever the hell it is you hold holy… to be true to me?”

She looked deep into his eyes. Even in the cold gloom, her eyes were piercing. “I swear upon our love, never to break your trust again.”

Colla smiled mirthlessly. “No Gods sacred to you then, eh?”

A dark look crossed her eyes, darker by far than any Colla had yet seen. It took him aback a little, so intense it was. She said only, “None.” And she turned, and led him on; and, watching her now with a curiosity cutting the smoldering mistrust, he followed.

And she led him on, into the untrod and primal wilds. For hours she led him, upon a path unerring, though he could see no track or trail which she followed; until at last they came upon a thicket-tangled hillock.

A circle of menhirs squatted upon its flat cap, barely visible against the stars. Colla smiled grimly. But she led the way up to the top, by a path he would have never found on his own. And, though the grim smile stayed upon his lips, he followed.

When Scáthach reached the top, she did not hesitate at the circle, as any child of Eire, no matter their faith, should have. Instead, she strode in with a purpose.

Colla did not follow. He stood at the edge, and peered closely at one of the stones, his nose almost pressed to the lichen-crusted and ages-worn surface; but he was wary not to touch the foul thing, not even to brush it with his clothing.

Aye. It was as bad as he’d thought. The lines were not the entrancing spirals of power that the Aes Sídhe had left behind. They were the unclean lines, squiggling, radiating, crushing into one another as they formed their madness-inducing shapes that were almost a pattern, almost a sign-language of witchery; but the meaning seemed to collapse in the mind even as the eye sought it out. As though mortal eyes could not see all that was etched upon the surface.

He turned to Scáthach; she was busy drawing signs in the frozen soil. She looked up at him, and called, “Come within, Colla. You’re safe here. None shall harm you.”

His smile was grim and fatal. “I’ll be safe? In a circle of the Cruima Sídhe? No mortal man is safe there, Scáthach.”

She stopped what she was doing. Emotion tugged at the corners of her eyes and mouth; but she managed to remain stony-eyed. “You have to trust me. I will keep you safe. I swore it, Colla–”

“You’re a slave of the Fomóire.”

“No.”

“Blood-sister to the Worms of the Earth.”

“Colla–”

“The Children of the Grave.” He shook his head. “Did you choose to mingle your blood with theirs? Or were you born of one of their corrupted wombs?”

Grief cracked her stony mask. “It’s not what you think, Colla. I’m not their sister anymore. I’m an outcast–”

“You’re not human!” Colla’s shout rang out through the chill air.

“I AM human, Colla!” Scáthach grasped at her breast, wrung her tunic between her fists. “I am human–that’s what I’m trying to tell you! I was a changeling–my mother, she…” Emotion choked her a moment. Her voice quavered: “I was bought and sold, even before I was born.”

But her eyes grew fierce once more, and Colla could not fully resist their piercing intensity. “Red blood flows still in my veins,” she said, and her voice was steady again. “Even if their damned ichor mingles with it, there is human in me–and that’s the part that matters! That’s the part of me that I chose, Colla. We all choose our family. And I chose solitude, rather than follow the ways of my kin.”

Colla felt his anger, his mistrust, waver. His gaze fell away from her.

And Scáthach spoke on: “Please, Colla, let me protect you. If you wish to leave afterwards, I’ll understand, but please believe me–I love you, I care for you. I follow not the fell ways of the Cruima Sídhe. I deal with the Fomóire, but I do not bow to them! Now, please… please, come within.”

Every instinct bred into Colla was holding him back. Every growled curse against the Worms of the Earth, every firelight tale of their horrors, told him not to trust one of their half-human witches.

But Scáthach had been kind to him. She had lied–by omission. She had lied out of kindness, had she not? She had lied to give them both peace.

Colla shook his head. The Morrígan protect him… he stepped into the circle.

Scáthach breathed a sigh of relief. With a fever fury she returned to the evil markings.

Colla strode up to her, and grabbed her arm. She jerked up, nervous and angry at his interruption. Colla’s own eyes were cold as he stared into hers. “I’ll trust you,” he said. “For now. But know, Scáthach, you can’t deal with the Fomóire, not without bowing to those monsters–not without giving your soul to them.”

Again, that dark and terrible look crossed her face. It was as though she aged a hundred years in the blink of an eye, and every moment of them a naked horror. She hissed, “I could tell you things about your Morrígan that would shiver your soul to a thousand pieces!”

She jerked her arm free, and reached into her bag to grab a bundle of herbs and a jar that contained a nauseous-smelling tarry liquid. She muttered, “There is much you do not know, Colla,” and, with one hand, she rubbed the herbs about along the marks, as with the other she began smearing the sickening ichor all over her body.

Again, the fear, the mistrust, returned. He backed away from her, keeping both eyes on her. Sure, she had been kind. Sure, she she had treated him well, with warmth and tenderness, when he had been helpless as a babe–and probably had bewitched him as well. What did he really know about her? She was a witch–a sister of the Cruima Sídhe… what else had she kept from him?

Those bandits had ascribed to her awful powers…

From the woods came the shout: “COLLA!”

He jerked round, one hand on the hilt of his sword. Past the opaque shadow of the ice-rimed scrub, he could see nothing. But he knew they were there. It had been his father’s shout.

And then they emerged. As shadow-men from the night, they materialized in an instant. His cousins, his uncles. Eight hardened warriors armed with axe and spear; and Ferghal at their head, spear in one hand, long, broad-bladed arming sword in the other.

But they made no move to enter the circle. They were nine against two, a weakling whelp and a woman in a witch-trance, muttering evil syllables to herself. But the O’Briens Dubh knew, even better than their fellow Irishmen, the dangers of the fairy-circles, and those of the fell Cruima Sídhe above all.

Ferghal handed his spear to the man by him, and with the free hand he beckoned to Colla. “Come out of there, boy.”

Colla stood still.

With a clumsy sort of gentleness, Ferghal spoke: “All is forgiven, boy. Come back, now. Come back to your family.”

But Colla did not move.

There was a silence, broken only by Scáthach’s fevered mutterings. Colla’s family glared at her, ranged about the circle like vicious wolves.

Like the bandits. Stronger, harder, meaner–it didn’t matter. Colla saw no difference in them, just then.

And as he looked at his father, at his cousins and uncles, hardened killers every one, he felt no love for them. He felt no leap of joy at Ferghal’s forgiveness, no desperate desire to run into their welcoming arms–into their cold and loveless embrace.

Grimly, he shook his head. “You tried to kill me when I ran.”

Ferghal gritted his teeth. “It was a moment of mad grief! It’s past, boy, I forgive you–Rónán attacked you without provocation, I see that now! Come back to us…”

But Colla shook his head again. “I saw it in your eyes, Pa. I saw how you hated me then. There was no love. The wrong boy died. Aye, you say you’ll forgive me now–but what of when you’re deep in your cups, and you begin to reminisce over Rónán, and grow angry again?” Colla’s grip tightened upon the hilt of his sword. “Shall I live my life with one fearful eye upon you, never knowing when you’ll decide to avenge the good son?”

Already the fury was mounting in Ferghal’s eyes. As Colla knew it would. The great, rangy old man growled, “You forget yourself. I’m your father, boy. We’re you’re family–you belong with us! Enough whining! Come back to us–I tell you, you’re forgiven!”

Colla said nothing. He watched Ferghal, tightened his grip on his arming sword, and waited.

The old man bared big, yellow teeth behind his beard. “You’d choose this gibbering witch, this foul child of the Fomóire, over your own blood? Is that what you want, boy?”

Colla smiled grimly. “We make our own family,” he said; like a clean bell Scáthach’s words rang in his head. He understood them now. “I’d rather have no family at all than the cursed pack that spawned me.”

He drew his arming sword, and stepped to the edge of the circle. “I don’t fear you anymore, father. You want me?” He raised the blade in challenge. “Come and take me, then.”

Ferghal’s face grew livid with the terrible fury of the sons of Black Turlogh. With an animal roar he advanced upon Colla. Colla involuntarily stepped back, his limbs now shaking with the cold terror of a coming fight, as Ferghal followed him into the circle.

The others made to follow Ferghal, but he waved them back. “He’s mine!” he bellowed, “I spawned the wretch–it’s my job to end his miserable, kin-slaying, worm-loving life!” And he swung his huge blade at Colla’s head.

Just in time Colla smashed the blow aside. The force of it numbed his arm to the elbow. The rangy old warrior was as swift as he was huge, and his blows rained down upon Colla, fast as he could deflect them. The great sword whooshed and whistled in Ferghal’s hand, a thing of battle-magic, a ribbon of steel all but invisible in the moonlight.

Colla was driven back like a sheep before the rod. He had no chance. There was no time to get his balance, no opening in Ferghal’s lighting-quick strikes.

The outcome was inevitable.

He felt the sword wrenched from his hand, before he could even see the bind and twist of Ferghal’s blade. He reached for his dagger, but Ferghal was too quick: the pommel of his sword smashed into Colla’s face and laid him out gasping upon the clammy and frozen ground.

The old warrior loomed above him, the corded muscles of his limbs bulging with fury. “You spoke true,” he growled, his face black with rage; “the wrong boy died.” And with a roar he lifted the blade to smite Colla.

The bloodcurdling scream froze him before he could strike.

Ferghal whirled about, the furious fear of dark magic in his eyes. Scáthach was bent double, shrieking like her soul was escaping. In her hand was embedded a grotesque, snake-shaped sacrificial dagger, the blood running down the dull blade.

Ferghal screamed, “Kill her! Kill the witch!”

With a cry the O’Briens Dubh surged forth. Ferghal leaped over Colla’s body, his sword raised to slay the witch before her dread magic could be brought to fruition.

But Colla threw himself about Ferghal’s legs, and with a cry of rage the old man fell in a heap a stride’s distance short of Scáthach. He snarled and smashed Colla’s nose with his boot. The boy fell dazed back, and Ferghal started to scramble to his feet–

But he could not rise. He gasped in pain and confusion as his limbs were jerked back to the ground.

The other Black O’Briens were stopped just as suddenly, in mid-stride so that they fell in cursing, shouting heaps. The shouts of anger abruptly turned to terror as they saw what held them fast. And Colla saw too, and what he saw made his very soul sick. The frozen earth all about them was churning, heaving; and from it emerged a swarm of huge worms. Boneless demons with frond-like heads that held black beaks that glinted in the dim moonlight as they squelched forth from jawless mouths.

They wrapped themselves about Colla’s family, and with those vicious beaks they lacerated their flesh and gorged themselves upon the flowing blood.

Ferghal roared with fury. His muscles bulged as he fought against the worms, struggled, with all the strength of his thews and the Black O’Brien fury, to break free. But all that strength availed him nothing, no more than the fly thrashing in the web.

Colla scrambled back, retching at the sight that refused to leave his mind’s eye. He turned away, squeezed his eyes shut, and stopped his ears as the screams of his former family reached a ghastly pitch.

There was the soft sound of the tearing of flesh. There was the dull thudding and shifting of earth cast about in huge quantities.

And then, there was silence.

Gingerly, Colla opened his eyes, and looked back. They were vanished. All nine men: Ferghal, mighty old war-hound, and all of his family, among the most formidable warriors in all of Eire. Only their abandoned weapons, and the freshly turned earth, dark and soaked with blood, told that they had been there but moments before.

Colla rose unsteadily. Dread horror left his limbs shaking and half-nerveless. It was with difficulty that he picked up his sword.

He looked up at the center; and there, regarded Scáthach. She lay in a shivering heap, her breathing ragged, her free hand clutching the one with the dagger through it.

Colla snarled, and turned to go.

But something stopped him.

He closed his eyes. With a steadying hand he cleaned and resheathed his sword, and turned back to her. She was so helpless…

Wearily, he strode over to her. A moment, he regarded her; and then, he shook his head, and muttered, “Damn you.” Very gingerly, he lifted her. Her hair was matted with sweat that was already turning frosty and frigid.

Holding her tight, so that his own warmth seeped into her, he turned about, and carried her back down the hillock.

________________________________________

Rev. Joe Kelly is a connoisseur of cheap beer, good metal, and quality fantasy. He has been published in Heroic Fantasy Quarterly and Wyldblood Magazine. He can be occasionally contacted on twitter at @reverendjoefake when he bothers to check it.

Karolína Wellartová is a Czech artist, painter creating images predominantly with the wildlife themes, nature studies and the literary characters. She’s mostly inspired by the curious shapes and a materials from the nature, but the main source still comes from literature.

From a young age she tried to express herself and her observations on paper. Painting and drawing were always the most important thing for her and visiting the local art school helped her understand the new techniques and the science of the colour mediums. She’s the award winning artist for “Best Book Cover in 2015” in Czechia.

Her work has been published in American magazines such as Spirituality Health Magazine, International Wolf, Metaphorosis, Orion, and Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. Check out more of her work at her website.