JACK O’WRAITHS: BELLS BEYOND THE SHORE

JACK O’ WRAITHS: BELLS BEYOND THE SHORE, by Phil Emery, Audio by the author and pending artwork by Andrea Alemanno

It was a bright, saltfresh sort’ve afternoon when Jack made his way into the little costal town. No one greeted him with word or smile, but perhaps that was the way with sea neighboured folk. He didn’t know, being a country lad. Mind you, he soon heard cheery singing and around one of the steep winding little lanes he saw a group of children circling in some sort’ve game. It was plainly an old game and an even older song. Jack thought he sniffed an old god or two hovering around it. As he ambled nearer, possessions sack slung over his shoulder and grinning, he was more sure. As he passed, the children had stopped singing and were merrily yelling questions at a girl in the middle of the circle, but the gods were still hanging around. Bull deities most likely. Jack might not know sea town ways but he did know about other things.

As was his habit he sought out a tavern. The landlord was gruff but professionally hospitable, particularly as his only other customers were a few old fishermen, supping grudgingly in miserly corners. As Jack began his second pint his host began conversation with the stranger.

“There’s a ship due in the harbour tomorrow, I’m told,” Jack explained.

“Mebbe,” replied the landlord, “but you don’t have the look of a sailor lad.”

A phlegmy agreement coughed from one of the corners.

There being no hurry in the heavy dinginess of the room, it was some time later when the landlord muttered a second question, like a coin being slid casually over the tacky bar counter.

“Perhaps you’ve heard,” said Jack pleasantly, “that there’s a war brewing.”

“Mebbe,” replied the landlord, “but you don’t have the look of a warrior either.”

Several phelgmy chuckles concurred.

Jack looked down at the straw flooring and considered. “But this war don’t have the look of that kind of war.” He smiled and nudged his head seaward. “It’s to be fought out there. It’s to be a war of storms and magic.”

An aged shoulder appeared beside Jack’s, the wiff of herring and mackerel and tobacco also coming alongside. “I spent longer than you’ve been alive, lad, tussling out there with the fish and the waves. You think you know about storms?”

“No,” Jack admitted to the fisherman. “but I know about magic.”

The fisherman cocked an eye. He sounded curious but not in a friendly way. “You’re some sort of magician, then?”

“Of a sort,” he admitted.

It was then that the bells started to toll, and he wasn’t entirely sure if it was that or his admission or just that evening was coming on that set the other customers drinking up and sloping off to the door. The landlord began to turn chairs and collect tankards as the last one left. It was when he picked up the bracket bar to slip across the door that Jack asked if he might have a room for the night.

#

Outside, the thud of the bar dropping into place was just as abrupt as the landlord’s refusal. But a wanderer was forever a stranger, and Jack had met that kind of hospitality in other places and never gave it much thought. Still, at least the bells had stopped, he noticed. He looked about for the church steeple but couldn’t spot it. Just as well. As a rule he avoided churches – troublesome places – just one god laid upon another upon yet another, he tended to find. And those bells had sounded queer to him, the tolling swaying and soft and muffled. The evening was quiet now. He looked down the steep cobbled lane toward the sea. He might as well bed down on the beach, and make his way to the quay in the morning to wait for the ship amidst the nets and lobster pots.

He found a sheltered cove. Even so the year was turning colder and unlike the country where the night closed in, the evening seemed to open up here on the shore. It made him uneasy. The sea was like some vast darkling field, endlessly furrowing itself. Its restless breath was coming at him, musing his fallow shock of hair. Nevertheless… He pulled a blanket from his sack and settled himself on the sand. The ship would be here soon enough. There were any number moving up and down the coast, he’d heard tell, looking to press or coax men into the realm’s navy for the coming war. As Jack had admitted, he had no particular skills of sword or seamanship, but his old man had always said that it was important to have a trade and he did have a trade of sorts that might be useful. Jack was a diviner. The world was ancient and full of old forgotten gods. They left lingerings of themselves like the dewy spiderwebs strung across meadows at dawn, and Jack knew how to make use of them. Magic would be needed as well as muscle in the battle ahead. Not that he was any great patriot, but most wars afforded opportunities for gain.

He pulled the blanket tight and closed his eyes, but he was used to nightingales and robins in his nights, and there was only wind and wave in his ears here. Sleep came hard. Though come it did. Only for the bells to start up again.

He yawned and pushed away his blanket and walked to the edge of the shore. Bells rang for all manner of reason. Births, marriages, deaths, even the beginnings and endings of wars, all summonings of one kind or another. There was something in them that called. They were calling Jack now, calling him into the water, for that’s where they were coming from. The sound of a bell on a crisp spring morning carried in one way, the sound of the same bell on a misted autumn evening in another. But these bells, coming from under the sea as they did, they carried in yet another.

The tolls were muffled and swaying as Jack remembered noticing before in the tavern, but still they called. Perhaps that was why the landlord had barred his door. Perhaps all the town did the same. Because the call was a strong one. Jack had no door. He looked down and sure enough he was already knee-deep in waves. And then waist-deep. And then the waters had enfolded him.

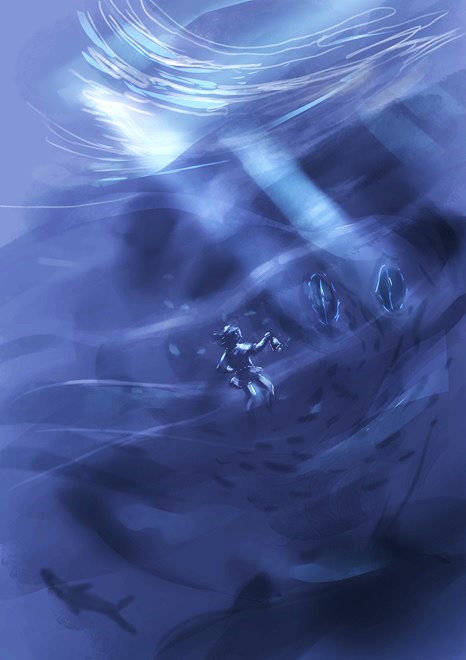

It was true that Jack was no great swimmer – but he’d contact with water gods before, and something of the skill lingered. Even so it was an uneasy passage. His usual dealings were with gods of hill and vale, of moor and fell, but the sea was vast and alien. Its gods equally so, it followed. The closest he’d come to such were lingerings in weirs and waterfalls and in the slanted shade between willow bough and brook. Perhaps he should turn back? But could he? The tug of the sobbing bells was getting stronger as he undulated deeper. And underwater or not, it was still a church they were tolling from, no doubt crowded with the remains of gods. Jack could take on one or two, but he knew not to tangle with more. Besides, he couldn’t shake the thought – a church under the water. He’d heard tales of the sea nibbling away at the edges of the land, wondered sometimes if eventually it’ll claim all… all his beloved dales and woods and fields, all drowned… The notion frightened him.

He tried to turn, to kick away, but he could feel the pull of ancient beliefs hauling him on, like a ghostly undertow. Then he realized how far he’d come from shore, and how long his head had been under water. The swimming he knew was left over from an encounter with a lake god some time ago, but to breathe salt sea instead of air, that was something out of dreams, and part of the summoning that had him. He put his hands over his ears but he could still hear the bells, or at least feel the sound pushing into his skull. Whereas the lost gods of land spread their echoes thinly over fen and farmland and heath, to be happened upon only from time to time, the sea, the great endless sea rolled its lingerings of past worshipped things in a ceaseless ponderous current. And what things they were… It occurred to Jack that if man prayed, why not fish and crab and seal? Were some of the ghosts he felt, the smells and glimpses and whispers of shoals and beards-like-seawrack and fins and tentacles and maelstroms and wrecks, were some of them the gods of other creatures, even of the sea itself? In the blue darkness Jack’s heart raced along with his fancy. Until the idea came to him…

These lingerings, whatever their nature, weren’t they still lingerings? And didn’t Jack know of such things better than anyone? So well that he’d been given the nickname Jack o’ Wraiths?

He began to swim differently. If he didn’t so much accept the pull of the bells he no longer exactly fought it. He began to stroke and twist craftily. Now he was squirming between the lingerings rather than into them. He grinned and bubbles trickled from his mouth. The tolls were louder than ever, but he felt their summons weakening.

Too late.

He could see them now, though see wasn’t perhaps the right word, looming out of the gloom.

The church had crumbled to little more than a lump on the seabed, but the bell-tower still rose out of it, stubbornly holding on to a crotchety ruin of its original shape. Turned out there was only the one bell, sending out its rippling demand through the water. But it wasn’t the common kind of bell. For a moment Jack forgot to defend himself from its pull and it enveloped him full force again. He floundered. Gawped.

Jack had heard about drowned churches with restless sea currents lolling bronze bell against tongue to send out a weird knell. But this bell had no tongue. Not all the tides and turmoils in all the seas could sound this bell. So it seemed that it was the strikings of tridents that was doing the trick here. Not that the mer-things squirming in and about the belfry had three-pronged polearms in their grasps – it was their three-fluked tails that were the culprits. Jack was pretty certain that they were just monsters rather than demons. But surely if they were just natural monsters of the deep their tails slapping against the bell wouldn’t have the same effect as a plain man-made clapper, even though their tail points seemed to end in shell-like hardnesses – like toe-nails. No, it would be the gods pealing the bell. One church with its god laid upon an earlier church with its own god, that one laid upon a still older. That was the way of places of worship, brick or henge or grove, they tended to plant themselves in the same spot time and again, and their abandoned prayerless gods would leave their lingerings, one atop the last. It would be the remnants of the gods who were sending out a summons – to the people of the town, to Jack, to these mer-beings with their toe-tails.

Toe-nails Jack repeated to himself, and huffed a grim watery chuckle.

He was close enough for them to notice him now though. One of them swam toward him curiously and he tried to turn away. But the pull of the tolling meant that for all his twisting about he hardly made any distance. The mer-thing grabbed for his arm and Jack caught it a slap in the face which had eyes and snout more fish-like than folk-like. More of them saw him now, began to come toward him. Jack squirmed against the summoning more than ever, and then he saw it as he kicked and a yelp bubbled from his mouth. They weren’t legs he was kicking with. Jack had a tail. He fought for breath he didn’t need, but kept the horror firm in his chest, not letting it spread. He thrashed with the tail but it was no more use than his legs against the pull. Another toll went out, shuddering him as it passed. It passed slowly. The water was like a sapphire soup of drenched mist – the tolls dragged themselves through it. Jack let his body dangle loose in the deeps and jammed his palms against his ears again.

The gods moaned their lost forgotten sadness through his hands nevertheless…

There were deities of fishing, of journey, of the sky, of the sea, of storm, of homecoming, of shipwreck, of loss, of grieving, of shanties, of little homely comforts and fearblown terrors. All worshiped in their time, all neglected as that time passed as time does. All that remained of them was bound up in that bell and the sombre beckoning it sent out. And Jack was being beckoned all right, just as he’d often beckoned the phantom leavings of the gods he’d encountered over hill and vale, field and forest, moor and fell above.

Just as he’d…

Now then, Jack. You’ve tried weaving between those lingerings to fox the summons. What if you gave off trying to defy that call altogether? What if you added your own beckoning to the bell’s? How would it like that, Jack o’ Wraiths? And he swished his tail and darted for the church.

In an instant he had his answer. The call didn’t like it – or at least didn’t know what to make of the change. Faces came at him as he swam, faces made of inky flappings like affronted sails, menacing spectral scrimshaw skulls, some manlike and some fishlike, not all possessed of noses and ears, but most with at least one eye and a mouth. Some of the mer-things tried to wrestle him as he sped, but Jack was fast as them or faster. Their webbed hands slipped off his tail, their scaled bodies shouldered aside as he made for the biggest of the faces, the one right in front of the belfry. Should he go for its eye? No. Not the eye. Jack struck it full in the mouth, the open, tolling mouth, and corkscrewed through.

He thrashed around in the cavernous colourless echoing dark, blindly butting himself into reefs of timber or shell or kraken tusk. And still he kept the horror down, and did what Jack did. He listened to the echoes. Drank them in. They were so loud and so ancient that they almost overwhelmed him, but he rolled them around his senses, savoured them. And then he knew what this god was. There were traces of spume and flotsam in the echoes, yes, but first and foremost of depths and swells, of salty vastnesses – this was a long-forsaken god of tide, of the unalterable, enduring, ebb and surge of the world. And now Jack spat it out. Now he was the tide. The power was bursting his lungs, his soul, each spew an ocean, an epoch of knells. But Jack had turned the tide and the knells no longer summoned but expelled. He rode the tide, the resound, out of the mouth of the god and up through the sapphire-blue mist-mire water, tolling the bell again and again, floating up, almost dying.

He crawled onto the shore almost dead. His knees ploughed through the sand, his trident of a fishtail gone. He ran his sopping head aground on shingle, still hearing the bell calling, banishing, calling, banishing…

#

The next morning was as bright as the day before, and Jack sat on the quay with back against a pile of lobster pots and tilted his face at the warm sun. Thinking. He was still weary. His thoughts were part cogitation, part dream. Fisherman chatted and whistled. Now and then a raucous patch of gulls scratched the air. Now and then Jack lowered his face and opened his eyes and squinted out to sea. He thought about the coming war. Second thoughts. He felt as if he’d just fought one. Certainly there’d be opportunities for a likely man like himself, but…

Eventually a sail appeared on the horizon.

…but there’d be death too if he weren’t careful.

So he watched the sail moving closer, as slowly but as surely as a tide, and turned over gods and storms and deaths in his head. And somewhere among all of them, beyond all of them, there might’ve been a deep distant toll of a bell.

________________________________________

Phil Emery’s work has been published in the UK, USA, Europe and Canada since the 70s. The novel “Necromantra”, was published in 2005 by Immanion Press, and reissued in a revised second edition in 2015. Various stories have been published in US and UK fantasy anthologies. Another fantasy, “The Shadow Cycles” was published in 2011. Besides two collections of short stories and verse, ‘The Celt in the Machine’ and ‘Arabesques from the Edge of Time’, and a collection of gothic monologues, Recent publications include tales in four Parallel Universes’ S&S anthologies. Another S&S piece is included in the Rogue Blades Anthology ‘Neither Beg Nor Yield’ and the absurdist cyberpunk graphic novel with artist Toe Keen, ‘Razor’s Edge’, was recently published by Android Press.