DEATH UPON THE TURQUOISE ROAD

DEATH UPON THE TURQUOISE ROAD: A TALE OF THE AZAlTÁN, by Gregory Mele, pending artwork by Justin Pfeil

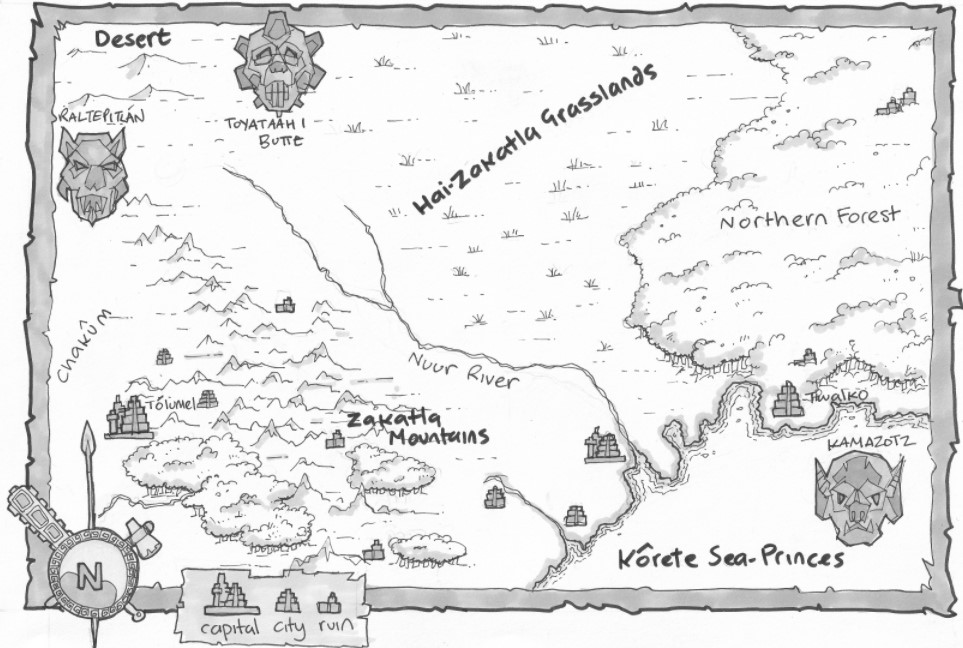

Tehanuwak, the Land of Obsidian and Bronze, is a sweeping vista of ancient city-states in misty highlands and steaming jungles of the deep south to the vast grasslands and burning deserts of unmapped north. At this vast land’s heart lay the Three Empires, proud and ambitious, none more so than that of Azatlán, City of the White Hearth. Ruled by the Naakali, a race of foreign conquerors, Azatlán’s legions push ever outward, seeking to bring more of the world beneath the yoke of the Living Sun.

Years before he’d find himself captain of a corsair pentecoster (see “Kamazotz,” HFQ #40) A young, mixed-race scion of an ancient Naakali family, Sarrumos Koródu answers the call to arms and finds himself captured in battle and offered the glory of an honorable death on a foreign god’s altar. Declining that honor, the exiled nobleman seeks employment and obscurity among the fiercely independent Naakali lords of the Kôrete borderlands, only to run afoul of an ambitious chieftain seeking to unite the clans through a bloody ritual to summon one of the Alien Gods that walked the world long before mankind. (See “The Path of Two Entwined,” HFQ #53)

Thwarting this plan, and saving Ahiga, chieftain of Clan Ma’iitsoh, Sarrumos finds himself in a rare position: an outsider welcomed into a Kwalankku camp. Formally adopted into the People of War under the name Ichtapu (“the Clever”) he spends nearly a year riding with the nomads across the grasslands, learning much wilderness lore, how to shoot the short native bow and hurl javelins while mounted, and even making peace with, if not developing a love for, the ill-tempered camelops. Growing homesick for city life and the company of his own people, he decides to move on, and is accompanied by Atsál, a young Ma’iitsoh brave, who is curious to see the ‘stone camps’ of the great empires. Trapping and hunting for skins to trade, the pair set out for Pàekilâr a caravansary on the so-called Turquoise Road that winds from the Empire, through the Kôrete, to the distant pueblos of the desert tribes. For Sarrumos, the dingy caravansary is a return to both the familiar, and a reminder of all he has lost; for Atsál it is his first glimpse of the wonders—and horrors—of civilization….

1. “SO, THIS IS CIVILIZATION”

They called it the “Turquoise Road,” but having grown up traveling the broad, paved Royal Roads that crisscrossed the Empire, Sarrumos found it hard applying the term to this winding trail of hard-packed clay and gravel that cut through the Hai-Zakatla grasslands then disappeared into the sand-swept deserts beyond.

Here, near the Road’s end, the caravansary of Pàekilâr lay awash in the smells and decadence of civilization, if few of its luxuries. A copper gong set atop the adobe lookout tower clanged, marking the midday hour, as if the flames cast by the Sun God’s burning shield to bake the moisture from a man weren’t sign enough. From within the dirty-white walls came the soft patter of a heavy, snakeskin drum and the hissing of rattles, accompanied by the agitated orgling of a male llama in rut.

“So, this is civilization,” Atsál said dryly from his perch atop his camelops’ tall hump, one leg draped over its neck as if ready to leap down at a moment’s notice.

“This?” Sarrumos snorted. “No, this is just a waystation. Think of it like a rash spreading in civilization’s advance.”

“You make it sound like sickness,” Atsál said, wrinkling his nose at a fly who kept obstinately landing on one of the thick stripes of red and white paint under his eyes: spirit-paint for safely venturing beyond his people’s lands.

“Perhaps it is,” his companion allowed. “All this, many days ride from a city, just so men can travel across a wilderness to trade cotton cloth for pretty blue stone, with a people they’d otherwise scorn.”

“There is strong magic in the stone, Ichtapu,” Atsál chided, using the name Sarrumos had earned among the Kwalankku. “That is the only reason the Anhusachi do not all kneel to the People.”

Sarrumos smiled ruefully to himself, green eyes sparkling. Anhusachi–‘Old Enemies’—the Kwalankku term for the cliff-dwellers. “Perhaps the People of War and we Naakali are not so different at that. Maybe that is what Ahiga-biheke wished you to see when he granted you permission to ride with me.”

The young brave considered that for a moment, eyes still taking in the caravansary’s squat walls. Youthful pride wanted to believe leaving the People’s camp was his idea, not his chief’s. “If this is not one of your great stone camps then why are we here?”

The older man, though he’d barely seen twenty-five summers, shifted in his saddle, and smiled, “We’ll hire on as guards to one of the caravans heading south, and let them pay us for your education in all things Naakali. Come!” Kicking his horse’s striped belly, he nudged it down the road toward Pàekilâr, the longer-legged camelops lazily following.

***

“What the hell is this?”

Rhukos Four-Lizard rose to his feet—six and a half feet and impossibly broad-shouldered in the llama-wool cloak and mantle he wore—his face incredulous. “Sarrumos! Heard you were dead; speared out in the bush by Kwalankku savages on a lion hunt!”

The smaller man shrugged noncommittally. “The rest of Lord Katelos’s party died so. I, however, had chosen just then to be hunkered down in a ditch battling my bowels when the attack came.”

Rhukos’s dark eyes widened, then he burst out laughing, a bellowing guffaw that made the mead-house’s walls reverberate; caravanners, roustabouts and herdsmen alike looking up from patolli-boards in annoyance, but none dared complain. Rhukos and his partner Tlekku were pochekka—caravan merchants who traveled the most dangerous part of the Turquoise Road into the lands of the Cliff Dwellers and then east to the Kôrete free-cities, and south to the imperial frontier province of Chakûm. They were also the last resort for an endless sea of peddlers, trappers, traders and less successful pochekka who needed money more than they needed fair trade. The pair dominated Pàekilâr so thoroughly they were at least, if not more, the authorities as the small, Imperial garrison that maintained the citadel.

“Saved by the shits? Sarrumos, the gods smile on you!”

Rubbing his pointed, auburn chin beard, the younger Naakali scowled as he usually did when the gods and his fortunes were mentioned in the same breath. “Yes, well, since then I’ve been traveling across the grasslands—hunting and trapping with Atsál, here.”

“Living with a Kwalankku? And he hasn’t cut your throat?”

Hearing his name and that of his people, Atsál looked between the two men. He’d learned smatterings of the Low Speech from Sarrumos but could not follow it when spoken at this clipped pace. “Ichtapu, is this the man we seek?”

Rhukos laughed again. “Ichtapu? You have a savage name now? I bet there is a tale there!”

“Not one you’ll be hearing,” Sarrumos said testily. He caught the eye of a stooped Chakumi playing patolli with a drunken caravanner and recognized the aging man as Tizoc, the caravansary’s mead-house owner, brothel-keeper, pawnbroker, and petty-trader for those who fell beneath the pochekkas’ notice. Tizoc sat with a long, clay pipe in one hand, the other placidly sorting out the dried beans used to play the game. He acknowledged the much younger man by lifting one side of a graying monobrow as if to say, You wish to trade with Rhukos? You take what comes with it.

Still chuckling, the big pochekka wiped away tears. “Well, whate’er the case, you need work now, eh? Fortunately, Tlekku and I have some for you. Sit down and hear it.”

Sarrumos nodded and took a seat, gesturing for Atsál to join them on the thickly woven mats. The young Kwalankku sat slowly, legs folded, back to the wall, eyes scanning the smoky mead-house with a combination of wonder and revulsion, nose wrinkled at the scent of so many human bodies kept from the open air.

The merchant waived over one of Tizoc’s near-naked serving girls, ordering mescal for them all.

“Rhukos, I have business for you, as well. Atsál and I have skins, good ones: four hipparion, a pair of lions and a toxodon that damn near killed us both in the taking.”

“Meh,” Rhukos said, waving his hand disinterestedly, “poor trading on hides right now. Besides, Wet Season’s coming to the coastlands; when the Nuur floods, we’ll be shut off from the south for a month or two.”

The mescal arrived and the men drank. Unused to alcohol, Atsál gagged, eyes bulging, as he tried to mimic the other men by downing it in one gulp. Rhukos laughed and called for another. Sarrumos used the distraction to think. It was true about the river floods; why were two wealthy merchants content to hibernate in Pàekilâr for months, rather than return to a city and make plans for the next season’s trading?

“Coming back to your skins,” Rhukos said, finishing his second mescal. “I’ll give you twelve bar-weights of copper, a third of that in silver. Mind, you don’t tell Tlekku. He’d have my hide. Hah!”

Sarrumos frowned. Three hundred taakin’s worth for two moons of hunting? “Leather workers in the bazaar would give as much.”

“In trade, maybe. Not in metal. Anyway, best I can do,” Rhukos shrugged impatiently. “Look Sarrumos: skin gathering is work for slaves and savages. Why don’t you take real work?” He leaned forward, his voice lowered. “I’m planning something out of the ordinary, something that could use a man with warcraft.”

“Why me?”

“You’re strangely scrupulous. You can shoot a bow, you can fight, and you’ve your pet there, whose kind raid along the river, and sometimes push north to hunt bison; he likely knows the country where we’re headed. Most of all,” Rhukos said with a wide smile, “you’re here.”

Sarrumos sat back, thoughtful, hand stroking the trimmed, auburn beard that hugged close to his jaw and came to a point over his chin. “And the task?”

“Not here. I explain in private.”

“How much is it worth?”

“Twenty copper bar-weights a month—at a guarantee of two months’ pay—and a share of what’s found.”

Sarrumos considered, spoke briefly to Atsál in his own tongue, who turned from his wide-eyed observations of the mead-house to answer in clear shock and no little anger. Sarrumos nodded. Turning back to Rhukos, he rose and put a battered taakin down on the table.

“No.”

Mouth dropping in shock, Rhukos half rose to catch the smaller man’s. “Wha—why?”

“Atsál says you offer nearly four times what you just promised for skins far finer than anything you’ll find in a land of broken stones and endless sand. Something’s not being said, and what isn’t said is usually deadly. So, our answer is no.”

He noted Tizoc looking at him over his pipe, making a small nod of approval.

“The pay is fair,” the merchant said harshly, “but what I’m after is my affair.”

“And keeping my skin whole is mine.”

“Come along and see Tlekku if you’d know more. It’s his scheme, after all.”

Sarrumos considered, nodded, and the three rose. Atsál knew Sarrumos was counted short and dark among the Naakali, but since he seemed tall and fair by Kwalankku standards, he hadn’t given that much mind. Now, seeing him walk beside olive-skinned Rhukos, his head barely at the man’s jaw, he looked like a stripling. If the Naakali were all like this, then he understood why the People named the invaders the Tall Men.

As he slipped his scabbarded sword’s baldric back over his neck, Sarrumo’s attention was not on Atsál’s gaze, but Tizoc’s. Those glittering, obsidian-dark eyes looked less pleased than before. Rhukos noted and turned.

“You see something important, old man?” he snarled. In two strides he crossed the mead-house’s dirt floor and slapped Tizoc across the face. The old Chakumi was light as a crane and the pochekka built like a bison; the blow sent him crashing to the ground. All fell silent as Tizoc turned from the earthen floor to stare up wrathfully at the Naakali.

“Chakumi scum, always nosing into better men’s business!” Rhukos said haughtily as they headed out the door. He looked back and spat.

Sarrumos was silent, but Atsál was appalled. “Ichtapu,” he asked in Tekwapu, the common language of the Grasslands tribes, “what manner of man treats elders so?”

“What is he saying?” Rhukos demanded.

Looking to the big man, Sarrumos shrugged, “He says among the People, an old man knows when it is time to wander into the desert without water, rather than make trouble for healthy men.”

Rhukos guffawed as he directed them around a corner. “The wisdom of savages!”

“He also says our help won’t come cheap. The only thing worth hunting for out there are camelops, and Atsál’s folk are closer to camelops than they are their wives.”

“They eat them and make leather from their skins!”

“They are the People of War—you have never met their wives.”

* * *

The hostel door barred, and window-flap laced tightly closed, the pochekka Tlekku smoked a long sikkar of fine southern tobacco, idly watching the smoke drift, before looking at the men and speaking a single word.

“Raltepitlán.”

Sarrumos shrugged indifferently.

“Long before Pàekilâr was built, and the land hereabout was grass, a city stood four or so days to the west. Perhaps the Cliff Dwellers’ ancestors built it, perhaps some folk now forgotten. Whomever, they were the workers of turquoise and had a chain of silver mines along this river.

“Where do you think old Tizoc’s trinkets come from?” Rhukos interrupted. “That crow says they come from pochekka returning from the Turquoise Cities—but no one ever sees those trades being made; and I’ve seen not a sign of such craft among the Nenlakati.”

Nenlakati— ‘Useless’—the Naakali’s dismissive term for any barbarians who dwelt beyond the Three Empires. Sarrumos bit his tongue and listened. Tlekku scowled at being interrupted by his partner and spoke over him.

“Pàekilâr is where the literal ‘Turquoise Road’ ends—from here it is trails and landmarks to find one’s way to the Cliff Dweller’s cities. But there is another highway, ye’ve seen it, no doubt.”

Sarrumos thought of the rotting cedarwood mileposts and the gravel highway that ran northwest until swallowed by the shifting sands. He nodded.

“The locals call it the ‘King’s Highway,’ but it runs nowhere.”

“Every road,” objected Tlekku, punctuating his words with his sikkar, “goes some place. The Highway of the King. What king? Of what kingdom? Retalpewa, the locals say. Well, look at this: Re— “king,” altepe—city or “citadel,” itlán—”place.” Well, Raltepitlán means ‘City of Kings’ in Classical Naakali.”

“Maybe there was a city out in the desert at one time,” Sarrumos conceded. “But if we agree it’s buried deep under the sand, how will you know where to dig?”

Tlekku smiled in self-satisfaction and puffed his sikkar before explaining what he and Rhukos planned. During a trade, they had come across a map of Raltepitlán folded into the journals of a long-dead pochekka-merchant of an equally long-dead clan. The chart derived from a manuscript of the even elder Tehanu civilization and was more accurate, Tlekku claimed, because the Godborn took minute care in filling their charts with precise distances and listed natural features that even desert sands would be hard-pressed to swallow. Yes, Raltepitlán was buried, but all they had to do was to follow the course of the Pàekilâr River until they found a set of rock features corresponding to those noted in the charts.

“And then?”

Tlekku shrugged and glanced at Rhukos.

“We uncover as much of it as we can,” the big merchant said promptly. “Not just ruins with trinkets, but the silver mines besides.”

“I see,” Sarrumos nodded. They knew more than they were telling him, of course. Moreover, Sarrumos was certain that something of immediate value was to be found in Raltepitlán, otherwise Tlekku and Rhukos would not be willing to wait out the southern Wet Season in Pàekilâr.

As a further enticement, Rhukos added that already he already had enough supplies and men to serve their needs, so they could set out almost at once. A short journey of four or five days, no more, so long as this first expedition was small and thus not hampered by too many beasts and men. Tlekku would remain in Pàekilâr should anything go wrong, or they needed more supplies.

Sarrumos finally consented on two further conditions: He must be his own master, and Atsál must accompany him.

“You two are partners. So are we. Anything we get out of Raltepitlán we split three ways; you and Rhukos each taking one, and Atsál and I splitting the third. Agreed?”

The merchants exchanged silent glances.

“We agree,” Tlekku said.

II. EYES IN THE NIGHT

Guided by the ancient, cedar mileposts lining the highway, the caravan dropped steadily down into the bowl-shaped valley that marked the edge of Otalwapán—the Burning Lands—while the snowy summits of distant mountain peaks mocked them with their promise of cool air and fresh water. Alas, their own path led down into a wide basin of grainy sand and ubiquitous red clay. By midday the air was so thick with dust that even the Sun God’s burning shield was reduced to a dim lantern hanging limply overhead, too weak to even form shadows.

On the fourth day, the highway ended. It had steadily decayed from hard beaten red clay and gravel, to scattered stones half-buried in sand, but their way northwest was guided by the cedar pillars thrusting stubbornly out of the drifting dunes. Now even they were gone, and the lonely caravan made camp for the night on the barren, basin floor as the scorching sun was replaced by a cold, uncaring moon.

“’Barely passed the half-way mark,” Rhukos explained, irritably. “Damned if I hadn’t thought we’d be here now.”

“The more fools we, for going someplace others have had the wisdom to leave be for a thousand years,” Sarrumos muttered in Tekwapu, as he and Atsál sat smoking an evening pipe beside a small fire. Rhukos was busy arguing with Meskli, the cook, over how much ground maize should still be left, while Meskli appealed to Jokopilko, the overseer, for support. The overseer shrugged and squatted down by the cookfire; his cloak drawn over his shoulders to block out the night breeze as he returned to lighting his own clay pipe.

Beyond the fact that Jokopilko was Chakumi, taciturn and efficient, and seemed less likely to draw Rhukos’s annoyed petulance than the rest of the crew, Sarrumos knew nothing of the man. The six other caravanners were mixed bloods from the Empire, lean and tough as wind-dried leather, but nothing to look upon. Their numbers seemed too few, six men, a small train of pack llamas, and only he, Atsál and Rhukos with mounts, though Rhukos had brought a second horse, should his or Sarrumos’s lame. The pochekka insisted the small party best to maintain the story they were on a hunt.

“Ichtapu,” Atsál said, fighting to be heard over the pochekka’s angry belittling of the cook, “there is still time to be away from this. Where we go….is not a good place.” He’d been silent for most of the journey, always seeming as if he wished to broach something, and had now determined to speak all at once. “There is a reason the People do not ride here. The sky is wrong, Wind and Sun do not favor the land. And the night…the night has eyes.”

In the year he’d lived among them, Sarrumos had learned that the Kwalankku might name a place ‘evil’ or ‘of no merit’ but would never admit they avoided it from fear. Still, Atsál spoke true—the clans always either kept to the northern foothills when venturing west into the desert, or looped south, to follow the distant Nuur River; they did not set out into the shimmering waste of this red-gold basin that held no regard for human life, even when it might cut a long journey short.

“Eyes in the night, Atsál? Are you an old woman telling tales to frighten children now? If the wastes have no life, then what is there to watch in the darkness?”

“I did not say the eyes belonged to the living,” the young brave said with dour seriousness. “It is said –”

At the same moment a strange, low moan echoed through the camp. It sounded something like a frog, something like a bleating llama calf, yet altogether like neither, nor anything else the two men recognized. The sound held on the air, then was silent, then rejoined, accompanied by a second voice, and then a third.

Rhukos was on his feet, back to the fire, staring out into the night. When only silence greeted him, he shrugged, laughed nervously, and turned back to berating his cook. Not long after, the weary men made for their bedrolls…only for the strange croaking-moan to call out once more. Sarrumos came to his feet, and saw an uneven line of amber lights, always in pairs, glinted and moving beyond the circle of firelights.

“Wolves,” he decided.

“Not wolves, Ichtapu,” his young friend whispered, eyes wide, scanning the darkness.

Rhukos gave orders to better secure the llamas so they could not break loose, to post a guard, and to build up the central fire and keep it going throughout the night. This done, they turned in, all but Atsál, who slept little and badly.

Sarrumos could see the youth’s shadow sitting upright, javelins in his lap, chanting a Kwalankku song to the ancestors for protection against the unquiet dead, the gentle burble of the Pàekilâr River mingling, almost keeping rhythm, as he sang.

***

“Gods Below!” Sarrumos leapt up from his blankets with a start, reaching for his sword as a hideous yelping and whining filled the camp.

The dusty air was orange with early-morning light, but not a caravanner was to be seen. Atsál was already on his feet, javelins, and small shield in hand as the demoniac whining echoed again from beyond the camp.

Moving stealthily forward, they came upon the caravanners on one of the dunes, watching as two men held a long pole with a hempen loop from which dangled a struggling, whimpering, near man-sized mass of blood and fur. Rhukos held an obsidian knife that dripped blood in a fist nearly as red. As the thing thrashed, a long coil of intestine writhed and wriggled serpentine-like between the furiously flailing legs to dangle and drag in the sand.

Sarrumos gasped in understanding. “He’s disemboweled a wolf.”

Releasing the lasso, they let the tortured animal collapse to the sand. Howling in agony, the fatally maimed creature stumbled to its feet and staggered away from the camp, its voice a sound of unspeakable torment.

“Caught it just before dawn,” explained the merchant, noting the two men’s arrival. He wiped off the knife, obsidian glinting a dark garnet with blood. “Should scare off its pack when they see—Hatûm’s swollen cock, boy, what are you doing?”

Atsál’s arm had drawn back and sent a javelin hurling after the maimed creature. The long flint tip caught it just behind the ear, and the wolf fell, its moans silenced. The young brave trotted towards it, his own knife already in hand, and finished the work. When he rose, his face was as dark as the blood covering his blade.

“Brother Wolf is a hunter! When he and Man make war, they do so under the Law!”

His voice was thick both with his accent and his anger, but his Low Naakal words were clear enough.

Rhukos let his knife fall, and his hand reached for the narrow-bladed bronze hatchet he wore at his side.

“I’ll handle any cur I catch in my camp as I wish,” the big man snarled, “and if a mangy pup forgets its place, I’ll slit his belly and pull his guts. You understand me, you Nenlakati filth?”

The camp was quiet, the caravanners watching the drama unfold, unwilling to intervene. Sarrumos caught Rhukos’s arm, speaking swiftly in the High Speech, which Atsál didn’t understand. He let his lips snarl in disgust.

“I came here for silver and turquoise, not a flea-riddled wolf pelt. Let’s eat and be on our way.”

Rhukos’s eyes turned to the smaller man half-mad with rage. Sarrumos hastily judged if he could draw his sword faster than the man did his axe, but then the madness passed and the pochekka chuckled.

“Such work does make a man,” he looked back to Atsál, “a real man—hungry. Meskli! Be about it!”

The tension broke, and the caravanners rose and made their way back to camp, Rhukos leading the way. Atsál remained where he was and would not move until he and Sarrumos had laid the poor creature out properly for Brother Vulture. They worked in silence, but when it was done, Atsál looked at his companion, his face sorrowful.

“I told you this is a sick land—and these are sick men.”

Sarrumos did not disagree, even if Atsál’s outrage surprised him. In the Kwalankku’s sacred Seven Caves he had seen their holiest wise woman skin a Naakali lord alive, and the memory still haunted his dreams. He knew his young friend would say that was an offering to the gods, whereas this was the work of wanton cruelty, but to Sarrumos, who’d fled a ‘noble’ death upon a foreign altar, the gods were no less capricious or cruel in Their sanguine lusts than Rhukos. But this was something Atsál would never understand, so he sighed, and chose his words carefully.

“You wished to see the lands of the Tall Men? To learn of our ways? Sadly, this is a part of them.” He put a hand on the youth’s shoulders. “At least we know now that it was wolves last night. Come, we should eat.”

Atsál watched him turn back to the camp but did not follow. He looked down to the slaughtered animal, cleaned his knife in the sand, and sheathed it, then looked back to Sarrumos’s retreating form.

“Not wolves,” he said softly to no one in particular.

III. A SHRINE UNDER THE EARTH

Life flourished in the desert by not making a nuisance of itself, whereas the caravan, with their bleating llamas, stomping horses, and sullen-voiced men, was a perpetual disturbance to the Burning Lands’ tranquility. As if to punish them for this disturbance, the Pàekilâr River ended as abruptly as had the King’s Road before it; the current growing stagnant, the waters shallower, until there was just cracked, red clay, and then, just sand and stone as far as the eye could see. Rhukos swore, scanning the horizon line for whatever mysterious landmarks he was expecting, clearly confused. Sarrumos looked at him in a combination of anger and disgust.

“I don’t suppose your ‘meticulous Godborn charts’ allow for the sands drinking the river dry?”

Atsál surveyed their surroundings with a keen eye, “Ichtapu, there are rocks here, worn smooth, probably by water, and the soil is packed hard,” he pointed out. “The waters are gone, but their spoor is not.”

“Wait, what’s that? You are sure?” Rhukos demanded—the first words he had spoken to the young Kwalankku since their standoff over the skinned wolf three days earlier.

Atsál nodded slowly. “The river’s corpse continues towards that wide flat space—perhaps it was once a lake.”

Rhukos rode his horse to where the young brave and indicated. He rode back and forth, clearly looking at something on the ground, then cantered back towards them, letting out a whoop of delight.

“Behold Raltepitlán, City of the King!” he cried; dark eyes gleaming. “The map told the truth, to the last word.” He reigned beside them. “According to the ancient pochekka’s notes, Raltepitlán stood at the edge of a cedar grove, by the shores of a small lake. Obviously, the trees perished long ago, but the mileposts came from somewhere. But the lake—as my favorite Nenlakati has seen—is still here, after a fashion.”

“So where is Raltepitlán?” one of the men asked.

“Why right beneath us!” the pochekka exclaimed, throwing wide an arm to encompass the depression they stood in. “Or, rather, right beneath that ridge of dunes beside this ‘lake’. And tomorrow we start unearthing it. For now, we camp. Meskli, get that cookfire started! Meskli!”

But Meskli, the cook, was nowhere to be found.

* * *

Jokopilko confirmed that the cook had been a few spear-throws behind when they came to the river’s end, but although there were rocks and dunes and ravines enough that one might run afoul of, doing so without being heard—and dragging the pack-animal with him—seemed unlikely. Rhukos demanded that Sarrumos and Atsál, the only others with mounts, ride back to see if the cook had fallen or come to some harm, but they found neither man, beast, nor footprints headed back east, to suggest he had abandoned them. Even if he had: alone, on foot, without supplies?

Night was falling, and they made an indifferent meal of Jokopilko’s cooking, made worse when the moon hid Her face, leaving them camped alone in a night as dark as a cenote, and a desert as still as the grave.

“We’ll look about after breakfast,” Rhukos told them over a tasteless but warm willow-bark tea that Jokopilko said would strengthen the tonalli-soul against the spirits of disease that haunted desolate places. “My intent is to have the men digging before tomorrow’s dark.”

“It’s a lot of land to search. Do your charts show the mine’s location?”

“No, but the barbarians dwelling near Pàekilâr have a legend that a road under the earth began from within a temple at Raltepitlán’s center, and the mine itself was considered sacred. Sacred usually means ‘wealthy’ where priests are concerned. Turquoise and silver, no doubt, perhaps jade, gold, mica—maybe even tin!”

“And you think the Anhusachi just left?” Atsál asked. “If they had such treasure, why not take it with them when the sands came to swallow their homes?”

Rhukos sipped his tea, licked a bit from his mustache, and shrugged, “Perhaps it was something they were afraid to move—or could not. Legend says that Raltepitlán was part of an ancient trade route, connecting the cities of the cliff dwellers’ ancestors to those of the Godborn, and half a dozen forgotten cities now turned to dust. This made them fabulously wealthy, but with that wealth came overweening pride and covetousness,” he smiled at that and gestured with his drinking bowl. “Note how these taletellers forever begrudge better men their wealth.”

Sarrumos, born to station and wealth and now a poor exile shrugged, “Or they begrudge them their contempt for those who have less.”

“Pah! The gods weave as They will; some are meant to prosper, while others serve! And that brings us back to the syndics of Raltepitlán! The legend says that, in punishment for their pride and failure in sufficiently honoring the Gods Below for the wealth of their mines a tempest of sand buried the city and all in it, none escaping save a single visitor who crawled from the sands and fled, to tell of its divine scouring.”

He finished his tea and sat back, then laughed hard. “I once thought it all just another pack of Nenlakati lies, but now we have both the charts and descriptions by traders who visited the living city. If it is real,” he smiled toothily, “then so, too, is the treasure.”

* * *

Meskli the cook never reappeared.

Four days passed, and the five remaining men had settled into the hard work of digging, their blunt, wooden shovels driving again and again into the concealing sand. Early the second day, they found pieces of broken post shafts, that perhaps had been markers, denoting a roadway or creating a gate-arch before some administrative complex. After this initial excitement, the rest of that day, and most of the next was nothing but moving sand and stone. Soon the prospect of half a dozen men trying to excavate an entire city became clear: it was madness.

Sarrumos spent a morning pacing out the area, then trotted back to where the pochekka-merchant stood, barking orders to his men, seemingly just to have something to do, and crouched down at his feet. As Rhukos watched quizzically, the shorter Naakali used his dagger to trace a long, irregular circle in the sand.

“If there was a lake, and this basin was its bottom, then it would be narrow and deep. Those cedar posts the men found here look to me like a city gate. And because they sit on higher ground…a land gate, one away from the lake, and any water-trade. If this was the gate nearest Pàekilâr, it must be the city’s eastern edge.”

Rhukos nodded slowly in understanding. “The chart notes say that the temple-mine lay at the city’s center, ‘between water and road,’ and its roof was high and domed.”

“Making the city long and narrow, like this lake, which would put its center here,” he cast about with his eyes, chewing his lower lip thoughtfully, thrusting down with his dagger into the makeshift map, then looking up to find its equivalent in the real world, “but that seems too close to the lakeshore to dig a mineshaft—”

“No! That’s it!” Rhukos said excitedly.

“How are you sure?” Atsál asked.

Ignoring the question, Rhukos pronounced they’d resume work at the new location tomorrow.

But nothing, even dying, is easy in a desert, and the workers’ renewed efforts were rewarded with a blustering wind that threw grit in their eyes and returned half a shovel of sand for each they hurled aside. Sometimes, they would strike a massive rock and need to split them with one of their basalt wedges and mallets; brutal work under a brutal sun, whose only reward for completion was a sip of warm water and a return to shoveling. They woke to find the wind had undone more than half a day’s labor, and as the sun rose, a new round of howling blasts swept through the camp, toppling a firepit stand, extinguishing the cook fire, and sending one of the workmen’s tents billowing down the ridge, like a rogue sail.

Dispirited, they abandoned work for the day, and hunkered down in camp. The workers muttered prayers, a few making offerings of blood and tobacco to propitiate the desert gods.

Perhaps in the odd, callous way of gods, They heard and were pleased, for the winds calmed and with dawn of the sixth day, the excavation began again. Just past midday, the sandy earth began vibrating under their feet, and Jokopilko, hurled down his shovel and shouted for the men to flee their excavation.

Unfortunately, the foreman was at the center of the works, and not a fast runner. He was the first to disappear as the ground imploded, an amber cloud of dust belched up, as sand, clots of red clay and fragments of rock were suddenly sucked down into the new crater.

When the debris had settled, Jokopilko and one of the workmen were gone. The remaining diggers would not go close, one announcing loudly that he would walk back to Pàekilâr alone, rather than further anger the dead city’s gods. Once the cloud had fully settled, Sarrumos and Rhukos cautiously picked their way forward, to gaze over the edge of the fissure.

The crater was about four man-lengths across, extended down easily half that, but as the sand continued running down the rupture, they could see at its center a smooth halfsphere of what looked like granite plates, cunningly shaped, and fitted together into a seamless dome. The foreman and his workers were nowhere to be seen, presumably lost in the loose sand still seeping around the revealed building.

“It is round as the moon!” one of the surviving men gasped in awe.

“Fickle Gods Above be damned, but we’ve lost our men, and found your temple,” Sarrumos said dryly, eyes staring, scanning for any sign of survivors. “I’ll have a look at what lies below—see if perhaps they are trapped in the sand along the edges, unless you’d rather be first?”

A rope was fetched and spiked with a precious bronze piton to a piece of limestone. Atsál and Rhukos steadied the end of the thick, hempen cord as Sarrumos looped it about his waist. Edging to the pit’s lip, the young Naakali exile checked his descent, then leaped boldly onto the sunken roof. When the dome did not instantly collapse beneath him, Sarrumos looked up, smiled, and waved—

—then plunged from view as a barrel-sized black hole appeared in the dome’s center when part of the tiling gave way.

Pochekka and Kwalankku ran to the edge of the pit, gaping in horror, the younger man calling out in his native tongue. For a long moment there was silence, then a tug on the rope.

“That. Fucking. Hurt,” came a pained voice. “But a pile of sand broke the fall, and I found a plinth to tie off the rope. Slide down.”

Atsál immediately went over the edge, letting himself descend on the taut rope, then dropped through the opening to land on a pile of sand taller than him, slipping and rolling in the loose grains until he rolled onto a hard stone floor. He heard Sarrumos chuckle but could see nothing but flashing purple splotches in the surrounding darkness, contrasted by the blazing summer sun peering down through the ruptured roof.

The sunlight faded for a moment as something filled the hole, then there was a heavy ‘thump,’ and Rhukos landed with even less decorum into the sand. He rose, sputtering, and looked about him, licking his lips thoughtfully. “Gods…there’s no supports, no pillars, the roof just…stands.”

“Mostly,” Sarrumos grumbled, still checking himself from broken ribs, and making certain his ankle would hold his weight.

“Where are we? It is a cavern?” Atsál asked, incapable of grasping so vast a space might be built by men.

“It’s a sunken chamber of some sort,” Sarrumos said, “look above, the railing.” The fractured dome was nearly four man-heights distant, and that span was split by a circular walkway, its railing of dark stone still intact, leaving the central, circular space of the great chamber open to the—presumably—subterranean chamber, where they now stood.

“Torches!” Rhukos shouted to the workmen above. In short order they held lit blazons and saw that while the upper floor was of finely joined stone, the walls about them were irregularly molded, and looked to be ancient, packed clay, and the floor of rounded river stones, set in a matrix of clay, and worn smooth from regular traversing.

“Alright, so what is this—gods!” Rhukos almost hurled the torch away as a hideous face, neither man nor lizard nor rodent, but something comprising all three appeared out of the darkness, its scales scintillating blue and gold, fangs blazing white.

Fortunately, it was made of stone.

“A temple, or a shrine, albeit to some strange gods,” Sarrumos said, gesturing about them. Along the circular clay wall was carved a series of niches, each filled with a simulacrum of things neither solely beast nor man, fashioned of stone, though painted in a cacophony of alabaster whites, scarlet reds, and bright yellows, rendering in the torchlight a momentary illusion of living flesh, snapping teeth, and gleaming eyes their ancient polychrome brilliance unfaded–hidden from the scouring abrasion of wind and sand that had turned the world above them to a perpetual beige.

“Oh, don’t worry, Rhukos, They don’t bite.”

The big Naakali pochekka glared at him and straightened his spine. “Well, the mine was said to be under a temple—so this is a good sign.”

“Better than you know,” put in Sarrumos. “While you and Atsál were rolling around in the sand, I explored that opening there, where there is no statue. It’s a corridor, and it immediately begins a gradual slope down into the earth. I think our path is clear.”

Eyes glittering with eagerness, Rhukos strode toward the opening, torch held before him, all fear of the idols forgotten. The passage was rough cut, but generally round, and its roof stretched a full arm-span about their heads.

“Hold,” Atsál said, reaching forward to grasp Rhukos’ shoulder. “Lying there—what is that?”

The big pochekka pulled free of the young brave with a snarl, but held his torch forward, its flickering light revealing the white and red of a corpse now more skeleton than flesh, but only recently become so. The bones had been snapped and ground so thoroughly that Sarrumos had some trouble in identifying the original animal, but Atsál pronounced it a wolf.

“What? Don’t be daft—wolves feast where they kill, not in their dens, and they don’t live so far under the earth,” sneered the merchant. “We made the hole down here. Or have you both already forgotten?”

Sarrumos shrugged. “We made one hole. Perhaps there is another.”

They moved on, Sarrumos walking behind Rhukos, thinking of the wolf, and wondering if the wolf pack were driven by sandstorms to take refuge in such a place, when he grasped Atsál’s arm and whispered to the merchant to draw his weapon.

IV. NEGOTIATIONS BENEATH THE EARTH

The two men heard the sound that had attracted the young Naakali’s attention, a light padding coming from a side tunnel. For a moment it paused, then it came on, and Sarrumos saw that the sides and roof of the cavern were tinged with a red glow—torches!

The glow neared them, until the red illumination rounded the bend, and they saw Tizoc, Pàekilâr’s mead-house owner limping toward them, a torch of twisted branches in his hand. Behind Tizoc appeared the lean form of Meskli, the cook, and behind Meskli four other men. Tizoc’s eyes widened as he sighted them.

“Tizoc,” Sarrumos said, his arm-length bronze sword already in hand, any relief at their missing cook’s reappearance fading at seeing the cook looked none-the-worse for a week lost in the desert and the four men were all armed. “What are you doing here?”

Tizoc laughed, or perhaps it was a cough, shaking his head. “Great One,” he said with feigned respect, “I might ask the same. But let us speak directly. I have long lived off the treasures found along the ancient highway, as did my father before me. From my father, who heard the tale from his father, I knew of Raltepitlán, the City of the King. I knew there was something of great price buried beneath the sand, in the sacred place of the elder people. I moved to Pàekilâr to be near the ruins, and for years have come to this dead lake, digging up relics of the city that was.

“Eventually, I grew bold enough to try finding this place, the heart of the forgotten kingdom, ignoring a lifetime of warnings by my father. A wind came up, blowing all I had done to waste, even though it was not the time of the winds, so I knew the Namorotl were angry.”

“Narmorotl?” Sarrumos inquired.

“Yes, Great One. The Dwellers Below the Sands; the demons of this place—my father said they were Raltepitlán’s descendants, twisted and cursed by their gods into monstrous form, but who is to know? They come on the wind and move in the night, and they feast on the dead and living alike. Now, I knew my father had been right—one might take from the sands what they spit up, but to try and compel them to reveal the city? Such was to invite disaster.”

“There are no secrets in Pàekilâr, Great One,” Tizoc looked to Rhukos, and his voice took on a hissing note, “so I knew your destination long before your caravan left for the desert. But how could you possibly know about Raltepitlán and its location? Fortunately, mescal—and a slave’s caresses—is a powerful incentive. I plied one of Tlekku’s men, and when he was drunk, he said that it was revealed by one of my women, whom I believe you favored a time or two when visiting Pàekilâr. Riiaya, you remember her, yes? So odd that she disappeared from my household almost ten moons ago, which was when last you left to return south.”

“Then tell me the man’s name,” Rhukos growled, “for he is a liar and I’ll see him horse whipped. As to Riiaya—I’ve bedded all your women over the years, old man, who can remember one, flat-faced barbarian from another?”

“There are those who suspect that this young woman,” Tizoc continued as if the pochekka had never spoken, “had fled from my service, hidden in the goods your porters carried forth. I wonder what you promised her. A place in your household? Freedom? Something that made her flee Pàekilâr, and quick to tell you where her master found the many ‘trinkets’ he offered for sale. And so, I offered Meskli here all you were paying him, and more, to report back to me when you drew near the lakebed.”

Dark eyes glittered in the torchlight and narrowed in anger, and he looked to Sarrumos like a magistrate. “And when Riiaya knew no more, he and that wretched Tlekku likely left her lying in a shallow roadside grave.”

“Liar!” Rhukos snarled, “I don’t leave girls dead by roadsides! And you, you Chakumi whoremonger, don’t care one whit what happens to your harem so long as the coffers fill.”

“No, a man who tortures animals and beats his men would never murder a harmless woman,” Tizoc hissed. “You see whom you have taken with Sarrumos?”

“Enough!” the young Naakali pinched the bridge of his nose between thumb and forefinger. “You both lie as easily as you breathe. Is there even a Riiaya?”

“Yes!” both said, then Rhukos frowned, having revealed he remembered the girl indeed.

“Well, there’s something. Tizoc, do you know Riiaya to be dead?”

His question was met with silence.

“Tizoc,” Rhukos said angrily, “my man lied.” His eyes shifted as he said it. “But you are not here to avenge a slave; you are here because we have done what you feared to do—and you wish to stake your claim. Fine—I will give you half of all we find in these tunnels.”

For a moment the Chakumi’s black eyes glazed with envisioned wealth, pondered. “And in return I and my men will not harm you, nor you and yours us?”

“Just so. But you must lead the way.”

The old man considered, then slowly nodded, and stepped ahead into the main tunnel. As his men followed, Rhukos hung back and whispered to Sarrumos. “They will try treachery; be ready to act swiftly.”

The young Naakali grunted noncommittally, remembering the disemboweled wolf and thinking Tizoc’s tale did not ring wholly false.

“Tizoc, one last thing: you must have seen that animal corpse we passed? It’s near fresh. What do you make of it?”

The mead-house proprietor shivered. “I told you, the Namorotl are not quiescent.” But he said no more, just turned back to the tunnel.

After some minutes, Tizoc halted and, lighting a fresh torch from the old one, pointed to

one of the walls. A couple of feet above the floor were carved words that neither Tizoc nor the two Naakali could read.

“The script must be as old as the Godborn’s glyphs,” Sarrumos observed.

“Pah, none of Tehanuwak’s savages knew how to write before our ancestors came,” Rhukos said dismissively, clearly disinterested.

Sarrumos was quite certain that was not true, but he hadn’t heard of any scripts used north of the Three Empires. Other than speaking to both the antiquity and obscurity of whomever had built the city, he wasn’t sure what to make of this, however, so he kept his own counsel and let Tizoc lead them on.

At the next turn in the corridor the Chakumi let out a gasp, the torch falling from his hands in his hurry to prostrate himself on the stone floor. His men swiftly followed suit and began murmuring prayers or supplications in their own language. To Sarrumos’s surprise, Atsál had stopped dead, mouth agape, then lowered his eyes, arms flung wide, hands palm up, as close to kneeling as a Kwalankku would come.

“What is it?” Rhukos demanded and was ignored.

The corridor ended in an octagonal chamber, whose walls were coated in a strange black lacquer, forming a kind of grout into which were set octagonal, turquoise plates; an unfathomable fortune spent as a kind of brickwork. The floor here was not rock, but a black obsidian that glittered as it reflected its torchlight, as did the large pedestal, as tall as a man’s waist and equally broad, made of that same glittering glass.

But it was what lay on the pedestal that held the men’s eyes: an ebon figure, carved from some unknown blue-black stone, depicting the most hideous deity Sarrumos had ever seen. Seated cross-legged, it was as tall as a man, a bulbous, batrachian thing, whose paunch draped over its folded legs and was supported by a pair of sloth-like arms ending in long claws. The wide face was something akin to both toad and sloth, but the wide smile and unseeing, silver eyes suggested a terrible, human sentience. Looking into that strange, smug countenance, Sarrumos, who’d had little good come from either the world’s multitude of gods or their mortal priests, shuddered and looked away.

Regaining his composure, Atsál whispered in Tekwapu, “Ichtapu, this is one of the Alien Gods who ruled the earth before Killer-of-Monsters made it safe for the People to walk beneath the sun.”

“It is just a cunningly wrought piece of stone,” Sarrumos reassured him, and hoped he was right.

The only one who seemed unimpressed by the hideous idol was Rhukos, who was shining his torch over the turquoise walls, running his finger along the strange, lacquered grout. Using the hem of his sleeveless tunic, he rubbed it briskly against the grout, then stepped back with a gasp.

“Silver! This is no grout; the plates are set in a wall of silver! Gods Above and Below, what wealth this city had!”

“And yet the gods swept them away,” Atsál murmured.

The words had barely passed his lips when Rhukos’s torch went flying, catching one of Tizoc’s men in the side of the head as the pochekka’s broad dagger plunged deep into a second man’s flank, up under the ribs. Shouts of surprise and anger; a spurt of arterial blood from a sliced throat; Tizoc’s own torch shattering into a bundle of flickering branches against the silver and turquoise wall, falling into dying embers.

Sword leaping to hand, Sarrumos searched for the sudden attack’s cause, but only Atsál’s torch remained illuminated, and all was madness. Something clanged against the wall; black obsidian flickered and flashed. The Naakali exile parried reflexively, cutting the attack aside with his sword, bright bronze snapping free a shard of black glass that cut a thin line across his cheek; weapon and weapon hand appearing again from the murk as his blade flashed, severing two fingers; a scream of pain, a gout of blood, black as the obsidian in the dim light. Shouts in a sing-sing tongue—Chakumi?—a shadowy form darting past him; a clang, a grunt; Atsál’s short exclamation of pain, followed by shuffling footsteps fading away into silence, as the groaning rising from the floor turned into a wet cough then silence.

Flint sparked and Rhukos’s torch flared back into life, revealing the smirking face of the batrachian deity, blood-spattered silver eyes twinkling. At its base lay Meskli, his face thrust straight through by a broad dagger blade, blood running freely down over his slack jaw to drip on his tunic. A second man, face scorched from the hurled torch, had stumbled no more than a stride before falling, while another of Tizoc’s men lay face down at his feet, blood running freely from a pierced kidney. Of Tizoc and his remaining men, there was no sign.

“Atsál,” Sarrumos called, “Where—?”

“Here, Ichtapu,” muttered the brave. “One of Tizoc’s men knifed me in passing. A scratch, no more.”

At Sarrumos’s feet lay a long knife, the blade broken in half. One of the natives must have cast it at him, the obsidian shattering against the wall.

“You lying whoreson!” he roared, rounding on Rhukos. “You gave your word to Tizoc he would not be harmed. Then you ambushed his men, for no reason—they’d not so much as moved!”

“I saw Tizoc nod, and his scum reaching for their knives. They were about to slit us open; no doubt as offerings to that,” Rhukos snarled, gesturing deeper into the shrine, where the grotesque idol lay. “And I did not lie; Tizoc lives, does he not?”

Sarrumos’s sword hand clenched whitely on his hilt.

“You and Tlekku lied about everything, Rhukos. There was never a set of ancient charts and journals; one of Tizoc’s girls told you where her master’s silver and turquoise trinkets came from. And you never saw Tizoc gesture to his men. How could you when you were busy drooling over that wall?”

It was Atsál who intervened, grasping his friend’s sword arm. “Ichtapu, this does not matter now. The Chakumi-man is loose and knows these tunnels, we must get above and find he and his. This will take us all, cousin. Do you understand?”

Still enraged, Sarrumos wanted to argue the point, but saw the wisdom in his young friend’s words. He also had heard Atsál emphasize the word ‘cousin’ and understood his meaning. The Kwalankku were scrupulous in giving and keeping their word to other men. But as only the nine Kwalankku clans were ‘the People,’ those scruples only extended to those outsiders they named family. In his way, the brave was telling him that once they were free of here, they owed the big merchant nothing. The Naakali let his sword hand fall.

“He’s right. We have no idea how many others Tizoc has with him, and our diggers come from Pàekilâr. Considering what a miserable bastard you are, Rhukos, it might not take much incentive to buy their loyalty. Back to the temple!”

They raced through the tunnel, passing the mangled wolf corpse, and soon saw the single beam of sunlight that streamed in from the broken dome. Hurrying towards the sand mound, they slowed as they spied the rope…or rather, didn’t.

Sarrumos swore. Rhukos called up to his men, but there was no reply to his repeated calls.

“Well, the hole is still open,” Rhukos reasoned.

“Of course, you idiot,” Sarrumos snarled. “Why go to the effort of burying us when we have no way to climb out? They just need to wait for thirst to get us.”

“Well, then we must call up to them and come to terms.”

“Terms?” Atsál asked. “You said Tizoc meant us murder. You hurled a torch into his man and gutted another. The only ‘terms’ we will be offered is to die, either in this hole or by their knives.”

“We have the turquoise and silver,” Rhukos argued feebly.

“Have? We are with it—and will die with it,” Sarrumos said, sitting down heavily against one of the demonic figurines ringing the walls. “All Tizoc needs to do is wait. And there is nothing you can offer equal to the wealth waiting down here. He clearly has control of our camp, and there he can sit, eating our food and drinking our water, until he is certain we are either dead or too feeble to offer resistance.”

Realizing the truth of this, Rhukos groaned. “What are we to do?”

“I’m thinking.” After a few moments, Sarrumos rose, glancing about the rock walls, the packed clay floor, the carcass that lay just beyond. “Perhaps we can escape the same way the wolves entered. A wolf is not much smaller than a man; there may just be a big enough opening we can find to squeeze free. But we should start searching while our light is good; I’ll take the second torch, Rhukos.”

“I think I’ll hold on to it,” the pochekka said, drawing back the brand he’d relit from Atsál’s. “Perhaps you and the savage can crawl out some den-hole scraped by a wolf, but I’m too big by far. I will wait in the silver room, where the savages up above cannot mock me, and wait for you to return.”

“Are you daft? I have no idea where we’ll come out, or how many men Tizoc has waiting above. There’s no guarantee I will be able to win through to you, nor—”

“Well, better that than stuck head down and arse up in an oversized rabbit warren. This, Sarrumos” the merchant said angrily, punctuating each word, “is why Tlekku and I hired you. Earn your keep.”

The younger, smaller Naakali bit off his retort and shaking his head, turned and took Atsál’s torch. They left Rhukos sitting by the entrance to the shrine.

“He stays to horde silver that is not his, believing that if we find a way back beneath the sky you’ll return for him.”

“I will,” Sarrumos said through clenched teeth. “I gave my word. Then, when our contract is discharged, I’ll strangle that miserable bastard myself.”

V. DEATH BY FIRELIGHT

Their travel through the caves was grueling, as they crawled, mole-like, through the dark places of the earth: they twisted and squeezed through narrow tunnels, climbed over tumbled stones, and more than once, were forced to double back on themselves. The experience eerily reminded Sarrumos of the first night he’d met his young companion; a grueling night of combat and horror in the Kwalankku’s sacred caves. Sarrumos had failed in his task to rescue his employer that night, but had saved Ahiga, Atsál’s chieftain, and been named a friend of their clan.

He hoped tonight’s outcome would be less ambiguously successful.

The air was stale, tainted with a pungent odor that reminded him of both dog and the ammoniac scent of bird droppings, though none were in evidence. Following deep claw gouges on the soft stone, the men were at times forced to choose between more than one course and settled upon always choosing whichever seemed to climb towards the surface. A few times, this proved misleading, and Sarrumos continued to nervously watch the guttering flame of their lone torch, realized they must find a way out to the surface before it died, for they had made so many twists and turns it would likely be impossible to double back to where Rhukos waited.

The trail was again climbing—and narrowing. Not a tall man, Sarrumos was forced to stoop, and finally to crawl on hands and knees. By the time he was worried they might have to wriggle on their belly like serpents, he saw his flame flicker and waver, and felt cool air blowing on his face.

“We’re almost out!” he called back to his young companion.

“What do you see?”

“Nothing! But darkness and cold air means it must be night in the desert.”

Fortunately, a glimpse of the stars provided just enough light before he crawled right out of the opening and tumbled to his death down the steep ridge. There was loose sand and stone all about the narrow opening, as if something had recently either tunneled out, or dug in, and with a little twisting, the young Naakali pushed through. Rising cautiously to his feet, he stood beneath a star-strewn sky. The dead lake basin lay directly below, and he could see in the distance campfires glowing like warm, earthly imitations of the gibbous moon that was rising now over the eastern horizon.

Legs trembling, struggling to stand straight after the long crawl, Sarrumos turned and helped Atsál out of the tunnel. The youth gasped as his companion pulled, and for the first time, Sarrumos saw the long, bloody streak running from under his buckskin vest, and dripping along his leg.

“You’re hurt!”

Atsál shrugged nonchalantly, but his seeming indifference was belied by his swaying. “A knife-bite along my ribs. Fear not, Ichtapu, I will not go to the Sky Father this night, only offer Him a bit of my life-waters.”

Sarrumos was less sure; the boy’s face was pale as the rising moon, and some of the blood still looked wet. There was nothing with which to clean the wound, and no real way to bind it here atop the small, clay butte, so he’d have to either leave the young brave here by the wolf tunnel, which seemed a poor idea, or hope Atsál’s bravado was matched by enough fortitude to follow and fight, if necessary.

Even as he debated, he heard a high-pitched howl in the distance, and decided.

“Well, if it’s but a scratch, Atsál, quit crying about it like a child, and let’s go.”

The boy stiffened, eyes flashing, and fetched up his weapons, before limping down the butte after Sarrumos toward the camp, whose fires gleamed brightly in the distance.

Sarrumos smiled to himself coldly: the last thing Tizoc’s men would expect was an attack from the rear; certainly not by a single Naakali warrior and his exhausted Kwalankku companion.

Presently, it seemed the least dangerous thing he’d done all day.

* * *

A wind had begun to rise, as, wriggling on their bellies, the two men climbed a ridge to look down onto the camp. Lit by a needlessly large campfire and the risen moon, they could easily make out the horses, llamas and camelops, penned just where they’d been that morning, and the small cluster of tents beyond.

“The beasts are restless; they keep looking back this way. Something spooks them.”

“The wind, perhaps.”

Atsál frowned and opened his mouth to speak, but fell silent, unconsciously clutching his wounded ribs.

The crater was outlined in the moonlight. No men were to be seen, but the reason for the large fire was apparent in the shadows that slipped here and there in the dunes—shadows that turned lambent eyes toward the frightened pack animals.

“Wolves!” Sarrumos began, then fell short as he peered deeper into the gloom, a hideous howling piercing the air. As he watched, the wind picked up, a low moaning sound that cast a spiral of sand before it as more than a dozen shadowy figures began converging on the camp.

“I told you, Ichtapu, my cousin, they are not wolves,” Atsál whispered, voice trembling.

Much as he might wish it, Sarrumos could no longer disagree. Wolves did not walk about on two legs, nor stand the height of a man. Nor did their howls contain the horrible cacophony of yips, grunts and meeping that filled the air now, making the animals pull at their tethers, bleating in fear.

“The Namorotl!” Tizoc’s voice screeched into the night. “Take up torches! Namorotl hate the light!”

Intent on Tizoc’s cries, Sarrumos barely heard heavy feet shuffling through the sand behind him, rolling over just in time to find a monstrosity charging, no, loping, at him out of the night.

Massive in shoulders and long-armed, its limbs and naked body were attenuated, almost desiccated, wiry muscles twisting sinuously under scabrous, sand-colored flesh. The creature’s spring covered twice the stride of a man, and Sarrumos only nearly avoided its leap, watching in horror as hands half-again the size of his own gouged the granite ridge upon which he’d lain.

He had barely drawn his sword when the crouching creature had spun about and sprung again. Bronze flashed in the moonlight, struck hard against a long, wiry forearm. Black blood—less than there should be—flowed, and the monstrosity howled, tossing its head in rage, long white hair thrashing about its face. Sarrumos did not hesitate but struck again, slashing at its gleaming, amber eyes. The monster drew its head back, and he attacked the eyes again, a thrust this time, that he turned into a backhanded slash into the arm it lifted to defend itself.

Atsál sprang at the fiend from behind, driving his hatchet into its neck. Sarrumos drove forward, thrusting the creature through the throat. While wrenching the blade free, the dying creature caught him with a back-handed blow that sent him sprawling to his belly.

Rolling over, the Naakali expected to find the Namorotl lying dead in the sand, but instead saw their monstrous foe leaping at a now prostrate Atsál. Sarrumos did not hesitate, simply drew his arm back and hurled the sword straight at the attacker, catching the strangely shaped beast through the thick muscles of its over-developed shoulders. Drawing his dagger, the Naakali exile sprang on the monster’s humped back, throwing his left arm about its neck, plunging his dagger again and again into the strange, papery hide of its flank.

Each time the blade came free that strange hide tore, then flowed—like sand—back into place, with only small traces of black ichor left to mark where there’d been a wound at all.

Widely splayed fingers grasped the choking arm, bending the bronze vambrace, one horn-thick nail tearing through the metal to rake the skin below. Adrenaline driving away any notion of pain, Sarrumos kept thrusting. The dagger buried itself to the hilt in an armpit. A spurt this time of the strange dark blood—whatever monstrous anatomy Namorotl possessed, they apparently still had hearts—and the creature swayed forward, thin lips drawing back from pointed teeth in a snarl, as it tugged weakly at the dagger’s hilt. Then it dropped to its knees and fell to one side, unmoving. Pulling free his sword, Sarrumos struck hacked savagely at the corded neck until the over-sized head came free. Only then did he reclaim his dagger.

Atsál had regained his feet and met his companion’s eyes accusatorily.

“Alright, they are not wolves,” Sarrumos allowed. “But they can be slain. Come.”

Cautiously they moved forward, Sarrumos limping a little, the torn skin over Atsál’s ribs bleeding freely now, the sounds of meeping and howls and the grunts and cries of men filling the night.

At least half a dozen of the strange shapes moved through the camp, joined in battle with the men. Loping shadows moved among the animals, snapping and growling, or engaging Tizoc’s men in combat. One had driven a spear clear through his ghoulish adversary, and it merely grasped the shaft and pulled itself to him.

Sarrumos began to go to the men’s aid, but Atsál checked him. “These men are not of the People and meant us death, cousin. But the animals are our escape from this madness.”

Hesitating, Sarrumos took a last look back at the demoniac battle occurring in the camp’s center, then followed his young friend towards the makeshift corral, where a pair of creatures was attacking the pack animals with teeth and claws. One of the horses had torn free and bolted, several of the llama were bucking and striking out at their attackers, their desperate cries enough to occupy the monsters’ attention as the two men charged in under the cover of Atsál’s hurled javelins.

Even with the advantage of surprise, and knowing now how the creatures moved and fought, it was a hard, desperate fight. The seemingly desiccated flesh had a strange, rubbery resistance to sword and hatchet, and while the creatures clearly felt pain, the organs inside their wizened bodies were either misplaced or slow to succumb to sword thrusts.

“Don’t thrust; edge and axe blows,” Sarrumos shouted to his young companion, as he hacked at back of a knobby knee. The creature hopped over the cut with a strangely lupine grace and raked with both claws as it landed. The smaller man leapt out to one side and his bronze blade sent a wide-splayed hand sailing into the darkness. The Namorotl looked at its stump in surprise and howled, then tumbled forward as Atsál, slammed into it from behind, bowling it over, and slammed his hatched repeatedly into a bony ankle until the foot came free.

Behind the Kwalankku brave, his last adversary, still transfixed by javelins, was rising unsteadily to its feet. Nor had their fight go unnoticed—two more of the creatures saw their fellow being overwhelmed and began loping towards them, nearly running on all fours.

“Quickly, while they skirt the fire!”

Grasping his horse about the neck, only its lead for reins and not so much as a blanket for a saddle, Sarrumos grasped the animal’s striped flanks tightly with his legs and let it do exactly what its nature desired: flee. Soon Atsál, mounted on his towering camelops, was racing after him.

With a last glance back, he saw more of the creatures bearing men away into the night, slung over one shoulder as one might a sack of maize. Remembering the devoured wolf in the mine shaft, Sarrumos shuddered and leaned lower over his horse’s neck. It needed no urging to flee.

***

The campfire’s blaze had died to little more than a cook fire’s embers, the moon fallen beneath the horizon as the rising sun cast orange and red streaks across a cloudless sky and tinging the granite ridges about the dry lake basin with fire. The two men heard the flapping of wings and saw vultures taking to the sky as they approached, but the ghoulish Namorotl had long since slipped away.

Not all the animals had escaped their corral, nor been brought down for good. The remaining llamas stood quietly watching the two men as they rode through the ruined camp. Atsál turned his own mount toward them to investigate, while Sarrumos dismounted and began picking about the destruction.

“Three of the llamas are dead, Ichtapu,” he announced, and “Rhukos’s horse is hamstrung; I’ll make a clean end of it.”

When he returned, wiping the blood from his knife, Sarrumos was stepping out of Rhukos’s tent, its flaps fluttering in the morning breeze.

“I can’t say how many men Tizoc came with, but I see no signs any fled and made it far before those things brought them down. The only prints leading away are…theirs.”

“And the old one?”

“No sign of him. But Tizoc’s a willey old thing. Let’s have a look at the crater. Perhaps he hid below when the fighting began.”

They walked down to the excavation, keeping a close watch on the nearby dunes, though Sarrumos suspected any creature that hated firelight would avoid the morning sun.

Sure enough, Tizoc sat on the upper ledge of the buried temple, back braced against the stone rail, puffing on his pipe as calmly as if he’d woken from a fine night’s rest.

“Good morning, Great Ones,” he called up to them. “The sun shines upon your glorious victory! Your defeat of the Namorotl will be remembered for—”

“As long as it takes me to ram a sword through that lying mouth. We defeated nothing. Where is Rhukos?”

“Where should he be? With his silver, and the Sleeping One.” He drew on his pipe and let the smoke out slowly. “Perhaps the Namorotl have taught him their means of worship?”

Sighing, Sarrumos found the rope Tizoc had used to flee, and lowered himself back over the crater’s edge for the second time in as many days. He stopped at the street-level ledge, bracing his feet against the rail, and met the eyes of the old Chakumi, who shrugged. “There is nothing worth seeing down there, Great One.”

“Atsál,” the Naakali called up to his companion, “I am going below to fetch Rhukos. If our friend so much as starts packing another pipe, put a javelin through him.” Then he lowered himself to the floor of the shrine and headed past the circle of forgotten deities, down the mine shaft.

They heard him moving about, then a long silence, before he emerged—alone—once more.

“Rhukos?” Atsál asked.

“There’s precious little to bring back up.”

* * *

When they had removed what remained of the merchant, and buried it in the sand, Sarrumos sat down and fumbled with his empty pipe, his fingers quivering as his mind and body processed all that had happened. He hid this by turning on Tizoc.

“So, you have Rhukos’s death on your head, old man, the death of our caravan, and your own men besides. Quite a day’s work!”

“It was the Namorotl who did the killing. I merely heard Rhukos screaming and knew that the demons had come. Did he not break open a place the gods had sealed against men?

“What are they?”

“Who is to say? The damned people of a damned city? Demons set by vengeful gods to see a dead kingdom remains forgotten? Does it matter?” As Tizoc spoke, his eyes glittered with a dark glee. “So arrogant, so sure—forever mocking Tizoc and the folk of Pàekilâr. I heard him die, Sarrumos, heard the Eaters of the Dead devouring him, taking in pieces the life I would have taken all at once. And I thought ‘this is good. This is right.’ Then I heard combat and knew that my men were overcome. So here I sat, waiting; a lame-legged old man. For if it were more Namorotl how could I flee? And if it were you, then I must hope you would see fit to let an old man live.”

Sarrumos’s voice was hard. “And if not?”

The old Chakumi shrugged wearily. “Is this place not proof none outruns the fate the gods have set them? If I am to die here, better by your blade, Sarrumos Koródu, than by the Easters of the Dead. But if it is to be so, Great One, then I beg you, do not bury me here as you did Rhukos, for this is an evil place, and I do not wish my flesh to feed those who haunt it still.”

* * *

Nearly half a month later, Tlekku opened his door to find a road-tired, and heavily armed man standing there. He quickly regained his composure.

“Ah, Sarrumos, at last! I’d almost despaired of your and Rhukos returning.”

In truth, Tlekku had been mad with anxiety since Tizoc returned alone, not a word about where he had gone nor what had become of his servants. Considering the old man’s prominence in Pàekilâr, and Tlekku’s likelihood of being trapped here through the Wet Season, the pochekka had held his tongue, even as his anxiety grew daily.

“Rhukos is dead; killed by wolves,” Sarrumos said bluntly. “I thought you might wish to know. I’m for the Road to Chakûm before the rains come. I’d advise you do the same—Pàekilâr seems a miserable place to be trapped for an entire Wet Season.”

He turned to go. The pochekka lunged forward, catching the younger man’s left arm, just above the dented bronze vambrace. “But the silver! The turquoise! If Rhukos is dead, then two thirds of all you found is mine!”

“Let go of my arm.” Something teased Tlekku’s belly, just above the belt. Glancing down, he saw the narrow point of a dagger poised to thrust. The merchant snatched his hand back as if burned.

“Your share of the silver,” Sarrumos said softly through clenched teeth, “lies where it has always been—in Raltepitlán, on the road beneath the earth. Tizoc knows the way; perhaps if you ask nicely, he’ll tell you. But I doubt you will find any in Pàekilâr fool enough to attend you. May the Gods Above smile on you, Tlekku at least as much as They ever have me—for the Gods Below surely do not.”

Turning on his heel, Tlekku’s curses ringing in his ears, he slipped into the street, a small smile curling the corner of his lips.

***

Atsál was waiting, already mounted on his camelops, holding the reins to Sarrumos’s horse. Passing through the caravansary towards the gate, they spied Tizoc’s small, unprepossessing home, slung aside the mead-house like a bad afterthought. The crook legged Chakumi sat outside; his long fingers dancing along the holes of a reed flute like the legs of a spider spinning its web. He looked up. Black eyes met green, and the old man nodded his head in acknowledgment.

“The rains come soon, Great One.”

“We are leaving now, before the storm arrives.”

Tizoc nodded, “It is wise; my bones say they will be sudden and fierce.”

“Alas, that we will not be here to see it. Life to you, Tizoc.”

Nudging his horse forward, Sarrumos rode on without looking back. Behind him the flute called on the breeze, as if whistling up a storm at the behest of Pàekilâr’s true master.

________________________________________

Gregory D. Mele has had a passion for sword & sorcery and historical fiction for most of his life. An early love of dinosaurs led him to dragons, and from dragons…well, the rest should be obvious. From Robin Hood to Conan, Elric to Aragorn, Captain Blood to King Arthur, if there were swords being swung, he was probably reading it.

His previous work for Heroic Fantasy Quarterly set in Azatlán includes: Servant of the Black Wind (#39), Kamazotz (#41), Heart of Vengeance (#44), Old Ghosts (#48), Father of Rivers (#50) and the Path of Two-Entwined (#53).