ISLE OF THE THOUSAND-EYED STRANGLER

ISLE OF THE THOUSAND-EYED STRANGLER, by Dariel R. A. Quiogue

Set in a fantastical version of the South China Sea and the Indian

Ocean, the Perfumed Isles are home to prince-turned-reiver, Pandara,

who has set himself the task of vengeance against the might of the

Wulongan Empire for ravaging his homeland of Zambail. But the Perfumed

Isles are home to more than imperial navies and princelings, for the

vanished gods of the ancient drowned world of Sundramala lurk behind

legends and beneath the waves.

________________________________________

The ecstatic pounding of drums and gongs echoed across the torchlit beach. Hearts thudded and feet stamped in time to the joyous beat, firelight flickering on sweat-slicked, tattooed bodies as men postured in a victory dance.

The revelers’ raucous laughter echoed against the star-shot evening sky as both players and dancers missed beats, for all were sloshing with arrack. Men bellowed incomprehensible snatches of song at each other in a dozen island tongues, pausing in their unmelodious efforts only to guzzle more palm wine from jugs. Now and again a man would suddenly drag the maiden serving him close for a slobbery kiss, then they would run laughing together, hand in hand, either for the line of beached galleys lining the shore, ducking under their naga or crocodile-head prows, or to the warren of thatched huts beyond the beach.

Pandara slapped his ink-patterned thighs at the ribald shouts following each such pairing, between bites of the roasted wild pig’s leg he held in one fist and gulps from the cup he held in the other. It was good to laugh again, to see the warriors of lost Zambail celebrating so for the third night in a row, years after the destruction of their home.

They had good reason to celebrate. The season’s raiding had been good, and other islands were echoing with the lamentation of Zambail’s enemies, for they had sacked no less than three towns and taken the same number of heavily laden junks. Pandara’s growing pirate fleet was cursed and dreaded across the Perfumed Isles, but they were safe and welcome here on remote Luok Pisang.

Luok Pisang’s chieftains had good cause to hate the Wulongan tribute fleets and the datus and rajas who bent the knee to their admirals, as Pandara did. For the sake of those tribute ships Luok Pisang’s powerful neighbors had impoverished the place, forcing the Pisangnun fisherfolk to strip their reefs bare to fill the Wulongan junks with live sea turtles, giant clams, and gem coral. The very gods and ancestors had turned their faces away at this abuse of their bounty, and now Pisangnun nets came up empty more often than not.

Pandara’s pirate fleet was like the scourge of the gods upon these common enemies, and the treasure the pirates were spending for their revelries would go far to keep the Pisangnun from hunger for a year or more.

So Pandara thought to himself, smiling, as he chewed the smoky meat. He sat alone, for he had sent the chiefs and boon companions who always ate with him to join the dancing. His thoughts ever haunted by the shadows of the past, he wanted time to think and consider his next move. How long dared they rest here, before word got out and his enemies gathered a fleet to catch him ashore? And where to next? And always, a red-hot coal that would never go out in his breast, how to make the Wulongans and their allies pay yet more for the destruction of Zambail?

A yelp of surprise, then a shout of “Hey! Stop! Catch her, you fools!” broke his train of thought.

He turned. Two of his men, among the sober few who’d drawn the lots to be his guards for the day, were restraining a wild-haired woman between them, while she struggled to reach him. Pandara’s eyes widened in appreciation. The woman was a fiery beauty, with smoldering, smoky eyes and pouting lips the color of coral, and a trim frame of a daily swimmer. He burned for her embrace — but then his gaze fell upon the array of talismans and amulets hanging around her neck, ornaments allowed only to a single profession, and he hurriedly signed for his men to let go then made a courtly bow.

She turned a withering glance at him. “Good, I see you still remember how to properly treat a baylan,” she mocked. “I need to speak with you alone, O Tiger of Zambail.”

Pandara motioned her to a seat beside his, clapping his hands for food and wine. A baylan, a shamaness, had to be treated with all the courtesy due a chief or a queen, as she spoke for the gods and ancestors. “Please, eat and share our feast, Speaker for the Ancestors,” he invited.

“I will partake, but I must speak first,” she replied, this time breaking courtesy herself. Vijadesans never discussed business before food and drink. But she unknotted her malong skirt, smiling sardonically at Pandara’s undisguisable excitement at the gesture; but she did so only to remove a small object she had secreted in the knot, retying the malong right after. She offered the thing to Pandara, and his eyebrows rose.

“I am Mala-Diwata, one of the only four baylan on Luok Pisang, and may I say, the most powerful here. But I cannot drive away the evil in this.” She held up a round gemstone, what looked like a pale citrine but with an inclusion in its center that made it look like an eyeball. “A girl of the town surrendered this to me earlier. One of your men had given it to her last night, but it gave her such terrible dreams she had to come to me.”

Pandara tensed. “You accuse one of my men of bringing a curse upon one of the locals? My men are all warriors, there are no warlocks among them — if there was, I’d kill him myself!”

“Do not be hasty, Pandara. The evil here is more ancient than that,” Mala-Diwata said. “An old, old curse, which I may have the means to lay to rest at last. My bloodline is also ancient, you see, descended from the priestesses of Sundramala, the vanished continent whose mountaintops now form our Perfumed Isles. And for generations, stones like this have been accumulating in our possession, passed on from mother to daughter. Destiny has brought them back to us, for we have a mission to fulfill.

“It was through you that this last one came back. It is a sign from the ancestors. You must take me, with these gems, to the island of Mabalete.”

“That island is cursed. Haunted,” Pandara objected. “I’ve heard no man who steps ashore there ever returns.”

“And it is my destiny, my gods-given mission, to end that,” Mala-Diwata declared. Was there a note of fear in her sanguine air? Pandara though there’d been a tremor in her tone at those last words.

“And how would you know that, Speaker for the Spirits? By what signs?”

“I will tell you,” she replied, her gaze becoming dreamily distant. “A long, long time ago, after the sinking of Sundramala, there remained only one temple to Kisaptala, She of the Many Eyes, and that was on what we now call Mabalete. My ancestors were her priestesses. But invaders came to the island, massacred the inhabitants, and plundered Kisaptala’s temple. They desecrated her idol, prising off the gems that were its eyes. The goddess, already forgotten nearly everywhere else, died that day.

“My ancestors recovered some before the raiders got away, but fourteen of those gems went missing. My mother bequeathed to me ten. Over the years, three more came to my hands. And now, through you, the last one has arrived. It is time. And by bringing me that final piece, the gods have shown me it is you, Captain Pandara, who will help me finish the task. I must lay the ghost of Kisaptala to rest.”

Pandara sighed in resignation. It was not the first time he had received a sign from the gods or ancestors. And each time had brought him only new sorrow. “Get yourself ready then. We sail tomorrow,” he told the shamaness.

Mala-Diwata put a trembling hand on his chest. “I have prepared for this all my life, as my mother and her mother did before me. But now that I am faced with it at last, I find myself feeling very small. Anything, any smallest thing, can go wrong. No baylan has ever tried to banish the ghost of a god before, and that ghost is angry, very angry. I want to sleep in a strong man’s arms tonight,” she said.

“Then come,” said Pandara. Leaving the fresh tray of roast meats and rice cakes behind, they padded silently into the town.

#

They beached at the shores of Mabalete two days later.

The hilly island rose gently from the sea at first, from a rim of gently shelving beach of white coral skeletons ground fine by the surf, suddenly steepening to form three uneven peaks all covered in thick jungle. Pandara took one look at it and decided he did not like the place, wondering how men had ever lived here.

Strange, he thought. Because on the surface it looks ideal. The jungle was of that vibrant verdancy one only saw in places blessed by regular and abundant rain, and rich soils beneath. The hillsides were not so steep they could not be terraced into rice paddies and taro gardens — and look, a mere spearcast from where they had landed was the mouth of a small river. Still, the landscape registered wrong.

It was too quiet.

No flocks of birds had risen from the treetops as they beached, no birds called and no monkeys chattered from beneath the rainforest’s eaves. There was only the drone of multitudes of insects.

And there was a strangely brooding character to the trees, all of them. Pandara raised a spyglass taken from a Wulongan captain to his eye, and the source of his disquiet finally came to him. There was no variety to the trees. No coconut palms waved their feathery crowns from the shore, no giant dipterocarps towered through the canopies of lesser trees, no giant ferns. Nothing but great, brooding, tendril-bearded banyans.

By now his men had noticed it too, and were looking doubtfully at him and each other. With good reason. These grotesque, parasitic trees, which smothered whatever host tree they had sprouted upon with twisting python-like roots, devouring even the ancient stone cities of the Nayyalingas, were the favored dwellings of spirits. And they had all heard of the island’s evil reputation.

His steersman Alonto spat over the side. “Well, at least we know the island deserves its name,” the man observed dryly. Mabalete meant full of banyans in the island lingua franca.

“It deserves the name and the reputation,” broken in Mala-Diwata as she came up the companionway to the burulan, the elevated fighting deck from which the two men observed. “I will enter the jungle alone. Let none follow. I do not know if I can find the temple and complete the ritual of restoring the goddess’ eyes before dark, so stay on the shore, below the treeline.”

She looked worriedly at the ogreish growths. In places there was not even a spearcast’s distance between the treeline and the high tide mark. “Perhaps I should’ve waited for the new moon — but delay is also dangerous. I could lose the gems, or they might get stolen from me, or the island’s curse take yet more victims. Thanks to the full moon, though, the tide’s beached us too close to the trees.”

She bit her lip in thought. Then, “Lay the out a bonfire in a trench, as we discussed earlier, and light it before it gets dark. Stay on its seaward side. Do not go into the shadow of the trees! If I am not back by tomorrow dawn, cast off and never come here again.”

“You will return,” Pandara assured her, stroking her cheek.

She smiled back at him. They had had a pleasant, though sleepless night together on Luok Pisang. “I will try.”

She went back below, and moments later they saw her moving up the prow, lithely jump onto the gunwales, then down onto the beach like a cat. Pandara smiled. He liked how that lithe, tautly muscled body moved. Then she turned around. “One last warning — take nothing from this island, you hear me? You may draw water and fish, but take nothing else.” Clutching the net bag filled with her ritual necessities and the accumulated gems, she ran into the jungle.

“Well, it seems our duty to the baylan is discharged for now,” Pandara observed. “We have nothing to do but wait — let us explore what we can see of this place!”

“I saw mussel-covered rocks there by the creek,” replied Alonto. “Let us go there.”

They descended to the beach, Pandara repeating the shamaness’ warnings and giving orders to lay a fire pit with the cords of firewood they had brought. At first he thought it had only been to help Mala-Diwata find her way back to the ship, but looking at the strangely animalistic-seeming trees, he began to imagine darker reasons. Grimacing, he hitched the ebon-hilted battle kris he always wore more securely around his waist, took the spear offered by one of his pirates, and set off.

Alonto called for men to bring water jars and follow, and soon a line of men cradling the great terra cotta vessels over one shoulder and bearing spears in their right hands were walking toward the creek.

He saw Pandara pause at the water’s edge, then inch in up to his knees poising his spear. The mighty arm flashed down, and there was a great thrashing in the water. “Stingray! Big one!” the muscular captain exulted. “`Ware the tail, I’m landing it now! This will be our dinner!”

Alonto grinned. “And I do see mussels, big fat ones. We shall prepare a celebratory feast for the Speaker’s success!” He waited until Pandara had maneuvered the fatally wounded ray onto shore, then waded in.

Moments later the steersman cursed sulfurously, hopping on one foot. “Demons take these barnacles!” Alonto bent down to inspect his injured toes, gasped, swore again — but this time he sounded almost reverent. He grubbed something out of the shallow creekbed, hit it twice on a rock to knock off the encrustation of barnacles clinging to it, held it gleaming wetly in the sun.

It was a bowl of gold.

“Throw that back!” Pandara cried, mindful of the shamaness’ warning. But he was drowned out by the cry of his men. They had been pirates too long. All the men who’d followed splashed helter-skelter into the creek, grubbing around the bottom, and soon joyous cries of “Look, here’s another treasure!” and “By the gods, what’s this?” rang across the beach as the men held up gleaming objects one after another.

Soon the men were looking speculatively up the stream. “The river washes this down from the hills. There must be an ancient temple there, just as the legends say! Let us find it!”

Alonto splashed back ashore, grabbed Pandara’s hand and slapped something heavy and familiarly shaped into his palm. He looked down. His fingers were already starting to curl possessively over the curved bronze hilt of an ancient kris, the iron blade long gone, but the bronze shone redly as if it had been newly forged, its ruddiness broken up by bands of gold wire and the winking of many little ruby and carnelian studs.

His mind screamed to cast it away, but he could not tear his eyes from its golden splendor.

The gold’s siren call fired Pandara’s heart and brain. Visions of the untold wealth that must lie upriver swam across his mind’s eye. The Perfumed Isles were fabled for their gold, but all the legends declared that was but a drop in the basin compared to the wealth of Sundramala. Gold. Gold enough to raise the ships and men needed to ambush the great Imperial Tribute Fleet itself, not just the little merchant junks that collected individual chieftains’ tributes and gathered them at the main ports. Gold enough to raise the throne of Zambail again, over a larger and more fertile island, gold enough to make himself a maharaja, a king over kings.

He blinked, shook himself as a sleepy lion tries to shake itself back into wary waiting, found his gaze irresistibly drawn back to the gold-crusted artifact in his palm.

“Leave the fish and the water jars,” Pandara said thickly, as if he’d just had too much wine, or relapsed into the smoking of opium. “We’re going into the jungle.”

#

They plunged into the jungle in a ragged, heedless mob.

Caught up in the gold’s net of enchantment, they forgot all of Mala-Diwata’s repeated warnings, ignoring the shouts of the crewmen left with the ship to come back. The ghost of some protesting voice rang weakly at the back of Pandara’s mind as he ran into the gloom then slowed as his eyes adjusted and the open beach gave way to the close and treacherous ground of an ages-old rainforest.

Hanging banyan tendrils brushed his face and licked his shoulders with softly sinister caresses. The brilliance of bone-white sand and sparkling sapphire sea gave way to dappled green shadow then a cavern-like gloom, and cavern-like too was the tortured labyrinth between the mighty, many-trunked trees. Some of the braided boles seemed as wide as his karakoa galley was long. Here and there, he caught glimpses of the banyans’ long-dead host trees rotting away in their deathly embrace, here and there the Stygian hollows left by the vanished host trees’ corpses yawned like the boneless maws of sea worms.

Sweat was soon rolling off his dark, bronzed body as he moved, for it was hot and stifling here, the sea breeze unable to penetrate the walls of thick vegetation. The musty odors of leaves rotting away without ever seeing sun again, and the thick moss covering the tangled roots snaking like pythons and crocodiles across the uneven ground, filled Pandara’s nostrils.

Another ghostly warning rang in his mind as he realized he could only see a mere handful of the score that had gone into the jungle with him, and again that warning passed, unheeded, like wispy smoke blown by a strong wind. He picked his way gingerly over massive roots and through snaking tunnels beneath arches of intertwined boughs, pushing away the hanging aerial roots as they increasingly impeded his progress. More and more Pandara began to get the impression something was watching him with a hungry gaze. He looked back over his shoulder more than once, expecting to meet the eyes of a tree crocodile or leopard — but there was nothing. Not even the tiniest of lizards or little vine snakes. Just more of the sinister trees.

He began to suspect he was lost. The uneven ground, riven as it was by writhing roots, half-buried like swimming reptiles, could no longer tell him which was uphill to the interior or downhill to the beach. Once, he caught sight of the sun through a tiny break in the canopy, and idly wondered how that orb could be ruddying like copper and the shadows so long. It had been a mere couple of hours after sunrise when they had entered the jungle.

Feeling an itch in his throat, for the jungle’s unusual levels of mustiness were irritating him, he fished a piece of dried wild ginger from his pouch and began to chew on it.

And now he realized he was alone. Where had his men gone? Had they found the temple and its treasure before him? They must not take it all! He needed the lion’s share for his dreams of vengeance — and after that, conquest! And now Pandara, whose open-handedness had grown his following from a single prahu’s ragtag crew to an armada of twenty karakoas, considered how to take treasure from his men if he had to.

The thought was like a dash of icy mountain spring water in the face.

What was I thinking, he berated himself. Desperately he cast about for some sign of the way back to the shore, for some clue to where his men were. Once again a vision of the gold awaiting him sprang before his mind’s eye, but this time he determinedly pushed that away. It seemed much easier now — and he stared at the dried ginger in his hand with horrified realization and hope.

Wild ginger! The purifying herb, placed by the gods on earth to protect man from evil powers!

His hand fell to his right hip, where he usually hung his conch shell trumpet, but it was not there. He hadn’t even been aware he’d lost it. He glanced up, noticing another of the rare breaks in the canopy, and his mind reeled, for the sky had deepened to a royal purple, shot with winking stars. How had the day gone so swiftly?

Pandara cleared his throat, preparing to shout for his men to gather to him — but before he could shout, a scream rang through the forest.

“There are eyes! There are eyes in the trees! Ahhhh!”

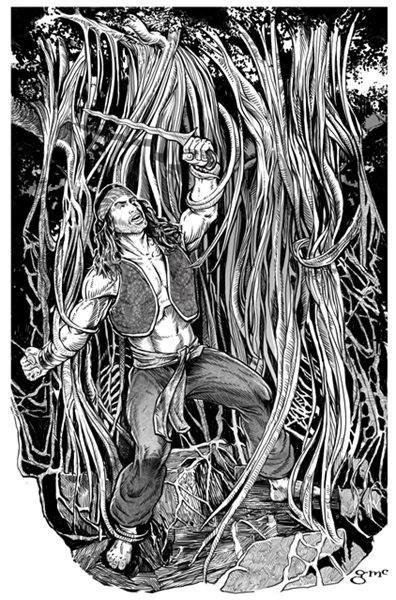

He stared wildly about him, whipping out his ebon-hilted kris in reflex. Eyes, scores of eyes, were indeed opening in the great banyan trees, in the branches, in the braided multiple trunks, at the bases of the enormous roots. And the branches, along with all the hanging tendrils, were coming alive. Reaching for him, as the eight-armed sea devils reach for a pearl diver caught unaware.

“Ho! Back to the shore! Back to the shore!” he roared at last, louder than he’d ever roared an order before, with effort so great it was like gouging his throat with a tiger’s claws. “Follow my voice!”

That momentary glimpse of stars had been enough. He knew the shore lay to the jungled hill’s west, and the constellation he’d spotted, the Stingray, pointed its tail westward. He cut down a branch looping toward him, ducked beneath a mass of groping tendrils, struck through a root that had wrapped around one ankle, and sprang away.

More screams rang from beneath the trees.

Electrified, Pandara ran for the screaming, hacking his way through the squirming, grasping growths all around him, heedless now of his earlier instinct to run for the safety of the treeless shore. Something was murdering his men, and by all the gods and ancestors, that was not to be borne!

Night’s gloom deepened as he ran, with all the swiftness of dusk in the tropics, but somehow he could still see. There were great swarms of fireflies in the trees, and their combined glow was enough to bathe the jungle in a pulsating, shifting, eldritch green glow that strengthened with the deepening night. In that glow twinkled back many eyes, eyes that had unmistakably once belonged to men.

He burst into a clearing and a scene of horror. Two of his men were hacking desperately to free another from the grip of the awakened strangler figs, racing against time as yet more and more branches and tendrils wrapped around the victim, while fending off the trees’ attempts to ensnare them too. The man in their grip was Alonto.

“Alonto! Hold on!” Pandara yelled. The veteran steersman had been his companion from the earliest days of his exile from Zambail, staunchly staying loyal through the travails of poverty, repeated defeats and shipwreck.

Alonto struggled weakly, his eyes bulging as the boughs constricted him like giant pythons. He was trying to speak and failing, but his eyes were locked on something on the jungle floor. Pandara followed the steersman’s gaze and saw the man’s kampilan, the two-handed islander broadsword, lying there.

Pandara understood at once. The kampilan could shear through the banyan’s fibrous limbs far better than his lightweight kris. He dropped the kris and snatched up the broadsword, screaming as he hacked at the boughs.

Just as Alonto was about to be cut free, however, more tendrils descended upon the steersman’s face, and he howled as the strands felt over his skull then plunged into his eyesockets, disappearing back into the canopy with the dripping eyeballs. The surrounding trees then gave a creaking wrench, and suddenly blood was spraying into Pandara’s face as Alonto’s muscular frame was torn into pieces.

His other two crewmen exchanged terrorized glances, turned on their heels and fled into the forest’s depths. “Stop!” Pandara yelled after them, but with a fatal delay to clear his eyes of Alonto’s blood. “Come back! We must fight our way out together!”

But the panic-stricken pirates ignored him. Cursing, Pandara picked up the kris — the only inheritance he had from his father, the Raja Toram, he had sworn to die rather than lose it — then made to run after them.

Before he could do so, however, a thick flock of fireflies darted past his face, then swirled as if celebratory dance around one of the trees. In their light Pandara saw two more eyes open, one at the crotch of a great branch, another lower down the trunk, eyes he knew all too well. Alonto’s eyes.

“Gods! How do you fight these things!” Pandara swore. But his ancestors refused to tell him anything, leaving the Tiger of Zambail to flee ignominiously into the night.

#

With a blade in either hand, the great kampilan in his right and the shorter, serpentine-bladed kris in his left, Pandara desperately fought his way through the grasping limbs.

Always he tried to bend his steps westward, his unerring sense of direction now back and reoriented thanks to that glimpse of the Stingray constellation. But the obscenely animated trees stopped him. Always the writhing boughs and tendrils were thickest in the direction he wanted to go, and as he whirled and slashed and ducked his tiring leg muscles warned him he was being driven uphill. “I am being herded, by the gods,” he growled in terrible realization, and the growing thought that this was one trap the famously elusive Tiger of Zambail might not survive.

But a red wrath was also growing in his heart, burning ever more fiercely as if the demons’ own blacksmiths worked the bellows, as he was driven past the gory traces of his men’s passing. Here a body was disappearing head-first into the hollow within one banyan’s trunk, being stuffed in by branches as a giant crab shoves bits of carrion into its maw while the hollow’s lips champed obscenely; there a man lay limply in the coils of a thick aerial root, empty eye sockets dripping red; another pirate howled as he was dragged bodily underground, into the hollow beneath a banyan’s rhizomes, and when Pandara tried to drag him free, the ground closed with a heave and he came away pulling the man’s torso, the man’s lower half gone.

He continued to retreat the way the trees were driving him, now and again making an attempt to break through, but forced reeling back by renewed assaults.

Pandara was a renowned swordsman throughout the southern isles, his skills honed in arduous training under ancient masters and furious battles on sea and shore — but those battles had been against men, and occasionally beasts. Enemies whose forms he understood, whose bodies moved in consistently known ways, against which he knew a hundred tricks of attack and defense. But the carnivorous, strangling banyans of Mabalete were nothing like these.

They attacked from everywhere, from every angle. The growths were so intertwined there was no telling where one tree ended and another began. Their eery coordination seemed to be as that of a single being. A being with neither front nor back nor side, and literally no blind spots, for the trunks and branches were studded all over with captured eyes. More and more of those eyes, still bleeding where they’d been freshly set, were known to him.

Only Pandara’s tigerish strength and reflexes were keeping him alive now, and only his anger at the massacre of his men keeping the terror from overwhelming his mind. And both his energy and courage, he knew, were being worn dangerously thin.

Once again he burst free of the grasping limbs through an explosion of fury, wheeling his blades in interlocking arcs, then ran for what seemed a clear path.

But the strangler trees, or the spirit animating them, had deceived him. Instead of finding a path downhill, Pandara found himself looking up at what must be the mother of all banyan trees, its main trunk as great as a hill, its roots embracing the half-crumbled remains of what had been a massive stone temple, a temple such none of the island peoples had built for over two thousand years.

Amid its tumbled stones was a great eidolon, leaning sideways at a crazy angle but kept from falling by the twined banyan roots. It depicted a woman, clothed in the flowing draped clothes of ancient style, a hand raised in a mudra of blessing — but her visage had been terribly defaced with chisels, the wide brows pitted where looters had long ago prised off the gems comprising her many eyes. The swarms of fireflies clustered thickest in the boughs above her head, and by these signs Pandara recognized Kisaptala, ancient Sundramalan goddess of the stars. She of the Many Eyes, whose sacred animal was the firefly, which in many of the islander tongues was still called the little star, or child of the stars.

Glittering with the fireflies that crawled over them, a score of tentacular vines snaked out toward Pandara from the great tree, and he backed away, blades raised in a last desperate defense.

A woman’s voice weakly called his name.

Pandara whirled. It was Mala-Diwata, straining with obviously failing strength against the roots pulling her beneath the ground. Her eyes were accusing. “You. You and your men disturbed the trees, waking them before I could complete the ritual,” she gasped. “Ah! I am sorry, O Goddess! I thought I could lay your ghost to rest, but Destiny did not will it! The Goddess’ eyes are lost forever now, they fell into the crevice that opened beneath me. Without them, no one can ever try the ritual again!”

Despair took him at last, and he dropped his blades to rush to her side. He knew it would be useless to try to pull her out. His strength was no match for the titanic power of the strangler trees, and to try would only doom Mala-Diwata to a death more painful and terrible than what already awaited her. He embraced her. “I am sorry! I will die here with you!” he declared.

Her slap rocked him backward. “I would not have called on you if I knew you were giving up!” she flared with a last burst of energy. She winced, her features contorting in pain as the roots pulled her under another few inches. “Pandara, haste, take the turret shell amulet from my neck! It is an amulet of Batara Linti, an heirloom we’ve had for generations.”

“What must I do with it?”

“Hold it up and crush it while calling upon the god! Call for lightning! Now!” Mala-Diwata cried, then screamed as the roots heaved again, pulling her completely beneath the ground.

Pandara tore the amulet from her neck. It was a black turret shell, rare enough by its coloration alone, but even more unusual for its twisted form, jagged like a lightning bolt instead of straight like a needle as normal for these snails. He raised it high, even as a thick aerial root began to coil around his waist. “Batara Linti, by this amulet and your bonds with the baylan Mala-Diwata and her family, I call you! Send down your wrath, Lord of the Thunderstorm! Cleanse this unnatural forest!”

He crushed the shell in his palm.

The heavens growled. The vinelike root uncoiled and dropped him to the mossy jungle floor as if in terror of its own, and the swarms of fireflies sprang into the air, winking out as they scattered. The strangler trees rustled even more violently than ever before, not of their own volition this time, but from a sudden blast of cold wind.

A serpentine tongue of blue fire arced from the heavens, so bright it shone through the thick canopy as if the canopy did not exist, and smote the mother trunk with a blinding, deafening blast. When Pandara could see again, the forest was bright as day, for the great banyan was ablaze. And the fire was spreading.

He snatched up his father’s kris and ran for the shore.

The flames roared behind him, echoed by the heavens’ own rumbles. More lightnings forked and writhed down, starting more fires. Pandara had to dodge between falling, flaming boughs, duck beneath the aerial roots flailing like a kraken in its death throes, sometimes even cut his way through with his kris. Somehow, by dint of sheer agility and strength of sword arm, he made it to the sea, guided at the last by the bonfire blazing on the beach.

“Pandara! Pandara! Thank the gods and ancestors, you got out!” the pirates left with the ship cried. “What happened back there?”

“The forest was possessed by a spirit gone evil and mad,” Pandara said, his expression haunted. “It took everyone. Even the baylan. Now Batara Linti cleanses the island himself, thanks to Mala-Diwata’s last effort to save us.”

The pirates shook their heads sadly as they returned to their posts. The strongest of the men set their shoulders against the karakoa’s prow and pushed it into the water with a will, though the waves, whipped up by the storm wind, lashed whitely about their legs. Not even the storm’s rising violence could dissuade them from leaving the accursed island in haste.

Within moments the warship was afloat, the waters churning with eery radiance as her oars stroked like eagles’ wings. Another deafening thunderclap, and the inevitable rain came hissing down in thick sheets. Pandara stood in the stern, stolidly enduring the chill beating of the rain though its great drops struck like hammers, with the violence only a tropical thunderstorm can have. The torrents washed away and hid the salt tears rolling down his tattooed cheeks as he pounded the stempost with a fist until his knuckles bled, mourning for Mala-Diwata and his lost men.

The curtains of rain soon mercifully veiled Mabalete from view. They also had their inevitable effect on the forest fire, which slowed, wavered, and began to die in patch after ragged patch. When the violent rain ceased, as thunderstorms quickly do, the forest re-emerged from the blaze blackened and riven in many parts but with most of the giants still standing. Banyan trees are naturally resistant to fire, and most had in fact survived. Over the remainder of the night, the fireflies began to return and drift between the still-smoking yet tenaciously living forest giants, first in twos and threes, then in flocks, and then in swarms.

Sunrise put the fireflies at last to sleep. Throughout the day, new leaves began to emerge, and by noon much of Mabalete was turning green again. When the sun died its daily death on the horizon, the fireflies came ablaze as thick as ever.

And the eyes of the strangler trees reopened.

________________________________________

Dariel R. A. Quiogue is a writer-photographer from the Philippines. In 1977, he was simultaneously exposed to Star Wars, Herodotus, Homer, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Robert E. Howard, and his brain has never been the same since. He now writes fantasy and science fiction in his spare time, flavored by his fascination for history, science, the sea, and the richness and diversity of Asian cultures. His creative motto is “Simple stories, powerfully told.” Quiogue’s works have appeared in The Best of Heroic Fantasy Quarterly Volume I, the Philippine Speculative Fiction Annual Volume 7, Rakehell Magazine, and his self-published story collections, Swords of the Four Winds and Track of the Snow Leopard.