JACK O’ WRAITHS

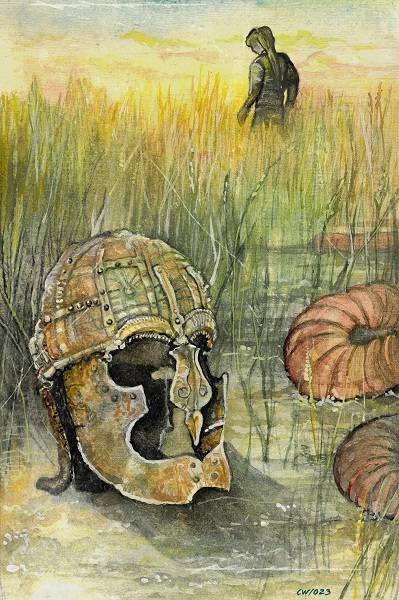

JACK O’ WRAITHS, by Phil Emery, with audio by the author, artwork by Karolína Wellartová

Jack stretched out beneath the afternoon sun and chewed a stem of wheat and drifted back to Nell’s face above his in the barn that morning. Motes of hay dust had floated down onto his bare chest and she’d kissed them.

“Jack Whitlock, you’re a terrible man,” she’d murmured.

And he’d smirked and pulled her down and kissed her back for using his given name rather than the one folk tacked on to him nowadays. And then he’d kissed her again.

By and by he’d pulled on his shirt and walked out, squinting into the sun, pushing back the lazy mop of hair fringing haggard eyes. His gait was lazy too. A meanderer by nature, he took what came his way, Jack did, as Nell could testify.

But now he had work to do.

Dangerous work at that.

Down here on his back in the field, with the crop practically grown harvest-high, he couldn’t see the danger coming, but when it did he was confident he’d hear it. It wasn’t long. The slithering was soft at first. Monstrous, but soft. As it came nearer softness gave way to harshness, to a neverending hiss of something huge moving along the ground. Still Jack lay. Made himself stay down even as his heart quickened.

And then the time was right and he jumped up, almost face to face with the worm.

Almost.

He’d known it would be big. He’d listened to the folk of Swallowfold and shrunk it a little in his mind’s eye since he knew villagers’ stories always exaggerated. Superstitious dread could be a terrible thing and Jack had had his doubts about the village smith’s drunken claim to have chopped the worm almost in twain and seen the two halves come back together. He’d known it would be long. In Jack’s experience there were two kinds of worm, those of size and those of length. What this one lacked in one it made up for in the other, not even reaching the ears of spelt but almost the length of the field. That was why it had been so loud slithering along. That was why when Jack jumped up he was twice as many yards away from the head than he’d expected to be.

As it happened that didn’t matter.

Just as he’d wanted, the worm saw him anyway.

Or heard or smelt him. Because the slits on the head could have been ears or noses as easily as they could have been eyes. At any rate the worm followed Jack as he backed his way across the field, and when he turned his back in the direction of the wood the worm didn’t stop or even seem to slow, but turned after him.

Jack had positioned himself between the ancient well where the worm was known to have made its lair and Swallowfold. Now he was leading it in another direction. As he danced backward he could see all the old paths that the worm had cut through the wheat crop, weaving tracks of flattened stalks and hulls, and he pursed his lips disapprovingly. It was poor ploughing. Jack knew. As a lad he’d once been a ploughman. His first inkling of his special talent came in happening upon a bit of something in a field he’d been ploughing.

It was nothing to look at. In fact he almost hadn’t. His ploughshare had turned it up as it passed and Jack only chanced to glance back as he woolgathered across the field. The glint of silver on the soil was a helm cheek, mysteriously burined, and as soon as he knelt to pick it up Jack began to feel a god hovering.

The helm cheek had belonged to a warrior, most likely. Even possibly to the god he followed – but most likely a warrior. Jack had hardly ever come across physical remnants of the gods he’d had dealings with since then, nor the remnants of those who’d worshipped them. A bit of something hard and solid wasn’t necessary, he’d come to discover. It was the ghostly remains that lurked about that he could hunt down and make use of. It was in his chest that the feeling always began. That sense of something otherworldly and once-powerful nudging at his heart, making it beat differently, making his breath quicken or deepen. That first time, with the soil-smudged helm cheek in his hand, the sense had whistled softly to him, like a breath of chill before the thunderstorm. He’d stood in that field not knowing what was beginning. Then he’d started to tremble.

Calls had whistled up to Jack from that helm cheek. Distant calls that swelled slowly into shouts. And those shouts were taunting at first, and then they turned angry, echoing with rage, and that turned into all manner of other shouts, of pain and despair. And there was also hate, which wasn’t, he’d realized for the first time in his young life, quite the same. And as the sounds rushed into him he realized too that it wasn’t just sounds of anger and pain and the rest, but anger itself. Pain itself. Hate itself. And there were sights as well as sounds. And smells and tastes. The sights were of louring skies and slashing sword and axe edges and hails of arrows and rearing horses and horizons of armoured fighters charging and waves of shields clashing on bleak heaths. And blood. And more blood. And Jack had realized, trembling in that field, that the sights were like the sounds – they were anger and pain and despair and hate. And the smells and tastes were the same. Jack had never known that anger had a smell – or despair a taste. They all clung to the helm cheek, remnants of the warrior who had once worn it, of the god that the warrior once worshiped. And Jack could tell that not only were they calling to him, he was calling to them. Later, in his travels, he learnt that what he did, what had happened to him, was something called divining.

Skip–trip!

Almost.

Jack was a good dancer, even backward in a wheat field, but had a tendency to be too-clever-by-far as his old man would say. He almost went over then, with the worm not too far behind. But a deft stumble and he was right again. Now just behind him, he knew, was a stank, a little pond at the back of the field. His bootheel detected a bit of softness in the earth, a wetness. He shifted left a touch. So did the worm. There was the pond, now, to his side, sun glittering between patches of frogbit. So next moment, as he knew he would, he felt the wooden bars of the fence on his back. In one nimble motion he climbed those bars and dropped onto the other side. The worm was not nimble. When it reached the fence it merely pushed its head up and over with the body following. The fence leant – but held. It was a supple and slimy progress. Below its head and thickened neck the worm’s body was slick. Nevertheless Jack hoped it would pick up a splinter or two. Beyond the fields there was woodland. Jack waited for the worm to gain tantalizing ground on him, then dodged into the first trees.

In some places in the wood, where the trees were well-spaced, it was easier going for Jack than for the worm. In others, where the trees were closer and the shrubs bunched about them and there was no clear path, the worm gained on him. At least that was the impression Jack wanted.

Finally the woodland thickets gave way to a clearing, as Jack knew it would. In the midst of which, were the charred remains of an old kiln. It was little more than a hump of ground now, and the nearby turf hut of the charcoal maker hardly more. Whether the generations of charcoal burners had been drawn to this spot because of the lingerings of a fire god or whether those ghostly tarryings had been drawn to the burners was neither here nor there. The lingerings were the important thing. That thing that suited Jack’s purpose.

The worm broke into the clearing now, slithering for him with a will. Jack had stopped dancing away. He stood in the middle of the charred circle. He could feel the lingerings all around, as he had yesterday when he’d first found this place. The place that suited Jack’s purpose. He waited calmly.

Not that he wasn’t nervous. The worm was a monsterous bugger, and those wicked slits – yes, they were almost certainly eyes – had a murderous look to them now. And if this one was a worm of size rather than length it might have opened its mouth now and stalactites of slime stretch wide enough to swallow any number of sheep and axes and reaping-hooks and farmers. But that wasn’t this one’s way. Jack knew what he was doing.

Jack had never put much store in the stories of worm slayers who’d donned jackets of razors and let the worm cut itself to pieces on it as it coiled around the slayer. He had something better than razor-blades. He’d found out on that day those years ago in the farm field, after all the helm cheek’s visions of war, when he’d come back to himself and looked around the field and seen all those infernal crows littered along the ploughed ridges. He’d shouted at them as he often did. But this time his shout carried all those sights and sounds and smells and tastes of legendry battles. And when its echo faded the crows hadn’t half-heartedly fled into the air as usual but were flapping their last throes in the brown furrows like dying soldiers of some shattered army.

Over time Jack had become skilled at finding the vestiges of old gods and drawing on their power. The land was full of them – ancient, forgotten, buried by neglect, wraiths of old faith.

He drew on this one, now, this old fire god, lingering in the clearing, as the worm began to curl around him. The smell of it was rank, as he’d often found with worms. It’d smell worse when it started to burn.

He could feel him, that old god – not a high god of infernos or burning cities, rather a quiet deity of charcoal makers and smiths. But that would do well enough. Fire was fire. Jack started to feel the heat from all those kilns and forges. Nevertheless the worm was beginning to squeeze. Jack called deeper.

He could smell the charred air, hear the hammering of metal, hundreds of years of heat now Jack’s tool. But the worm was still squeezing. Jack called deeper.

A piece of forge-hot iron stabbed his chest. No, not iron, not hot, but a different kind of pain. And now Jack o’ Wraiths was no longer calm as he realized his mistake. He would’ve struggled if the pain hadn’t instantly paralysed him. He’d been lazy yesterday when he’d found this site. He hadn’t delved deeply enough. He should’ve known better. All gods, even quiet neglected ones, were dangerous. In the far ago past before he’d been forgotten, this god had had a lover. Not of fire but of water. She was not a goddess of floods and oceans but of brooks and little stanks like the one Jack had stepped into on his way here. And the fire god had lost her. Perhaps she had been abandoned by people, by time, before he’d been? This loss was what Jack now felt – the anguish of lost love.

There was the pain of his ribs, too, of course, as the worm tightened, but that was as nothing in comparison.

Jack had never been in love. Had never known such hurt existed. Perhaps only gods could feel it? And in delving into the god’s power he had also tapped that pain.

He tried to think, to work out what to do. A rib-bone panged. He tried harder. If the fire god’s power was failing him, what of her? If the bond between fire god and water goddess was so strong could he draw on her too? If the worm was slick enough, if he could struggle free, cracked ribs and all, could he manage to make his way back to the stank in the field? Could he lure the worm back? If he could tempt it into the glittering, frogbit covered water, he could turn it bottomless. The worm would be sucked down to the underworld.

If.

The worm wasn’t slick enough, its grip too tight around him.

Think Jack.

He had time, the worm wasn’t in any hurry to crush him to death. But the longing… The fire god’s pain… Hundreds, thousands of years of longing… Timeless seasons of wound…

But there was something about the goddess… Jack’s desperate thoughts chased it, groped after it. He felt the fire god’s power, but he could catch glimpses of the water goddess herself. The sensual swoop of cheekbone, the curve of eyelash.

Then he had it.

The lingering was hers. The pain was hers. It was her longing for the lost fire god that Jack had felt in the charcoal burning clearing – a longing so powerful that it overwhelmed and masked her ghostly essence in this place. The realization caused a sharp intake of breath, which the coils of the worm thwarted. But Jack ignored the crush. He delved through the yearning for the fire god and went deeper. He felt her fully then. The crestfallen slide of thousands of brooks over thousands of weirs, the eternal ache of droplets in deep caverns turning to stone. Like timeless sobs. Like tears. Like tears.

His breathing was a weak tugging in his chest now. But that was it. Like tears.

Not fire. Not water. The way to slay the worm lay in the sadness of gods.

Jack’s haggard eyes rolled up in his gasping face as he fought the darkness that pressed in on him. He reached into the goddess’ pain…

sorrow… sorrow…

…and cupped some of it to him.

Then he delved again, this time into another part of the longing, the part that was fire. He had them both, now, cupped. Then he raised the goddess’ pain. Slowly. He cursed himself for not beginning with the fire for lifting the sorrow was somehow more difficult. But finally he had it. Then he moved the fire and sure enough this was easier. Then, when the goddess’ pain was above the fire that she longed for, Jack loosened his hold on the pain and let it fall. Like tears. Onto the fire. And he heard a sigh. Like the sigh of glowing iron plunged into water…

sorrow… sorrow…

…and as he’d hoped something rose from the sigh. It was as hot if not hotter than fire, a ghostly vaporous burning. And Jack cupped that, now, and went about his work. His heart began to quicken in a familiar way, different from the beating of fear or effort. He had drawn power, and like the spiracle on the top of a charcoal kiln he was going to vent it.

And presently, finally, sure enough, the worm started to burn.

There were no flames, but little shudders began to run through its coiled body. The pressure on Jack began to ease. Soon he was able to take in his first real breath in an age. His ribs spat out sharp tearing protests – but it was a simple, sweet, uncomplicated smart and he sucked it in gratefully. Almost at the same moment the worm began to shake rather than shudder, to writhe. Yet it stayed wrapped around Jack, almost as if it was the one trapped. The skin was no longer slimy but dry. Scalded. Still it shook and writhed and Jack’s ribs jangled with agony.

But still he laughed.

Just before night he managed to maul free from the dead blackened coil like a bruised pupa wearily struggling from its cocoon. He sprawled in the clearing and slept a while under the gentle soughing of the wood. As he dropped off he considered returning to Nell, but on waking he thought better of it. After all, the village had already paid him, so he set off another way, wherever that way was.

Still something troubled him as he hobbled along. In a sense his skills had reunited the mourning water goddess and her fire god. He’d felt it as he’d left the clearing. But there was still suffering in the lingering ghostly remains. Pain of a different sort, but still pain – Jack couldn’t quite put words to it.

The idea of love deep and lasting enough to cause such pain haunted Jack all the way until dawn.

________________________________________

Phil Emery’s work has been published in the UK, USA, Europe and Canada since the 70s. The novel “Necromantra”, was published in 2005 by Immanion Press, and reissued in a revised second edition in 2015. Various stories have been published in US and UK fantasy anthologies. Another fantasy, “The Shadow Cycles” was published in 2011. His PhD thesis on the genre is entitled “Revivifying the Ur-text”. Latest publications include the S&S tales ‘Seven Thrones” and ‘Demonic’ in the recent “Swords and Sorceries’ Parallel Universe” anthologies and “The Rider in Darkness” at Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. The absurdist cyberpunk graphic novel “Razor’s Edge” is due out from Android Press next year.

Karolína Wellartová is a Czech artist, painter creating images predominantly with the wildlife themes, nature studies and the literary characters. She’s mostly inspired by the curious shapes and a materials from the nature, but the main source still comes from literature.

From a young age she tried to express herself and her observations on paper. Painting and drawing were always the most important thing for her and visiting the local art school helped her understand the new techniques and the science of the colour mediums. She’s the award winning artist for “Best Book Cover in 2015” in Czechia.

Her work has been published in American magazines such as Spirituality Health Magazine, International Wolf, Metaphorosis, Orion, and Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. Check out more of her work at her website.