FATHER-OF-RIVERS, A TALE OF AZATLÁN

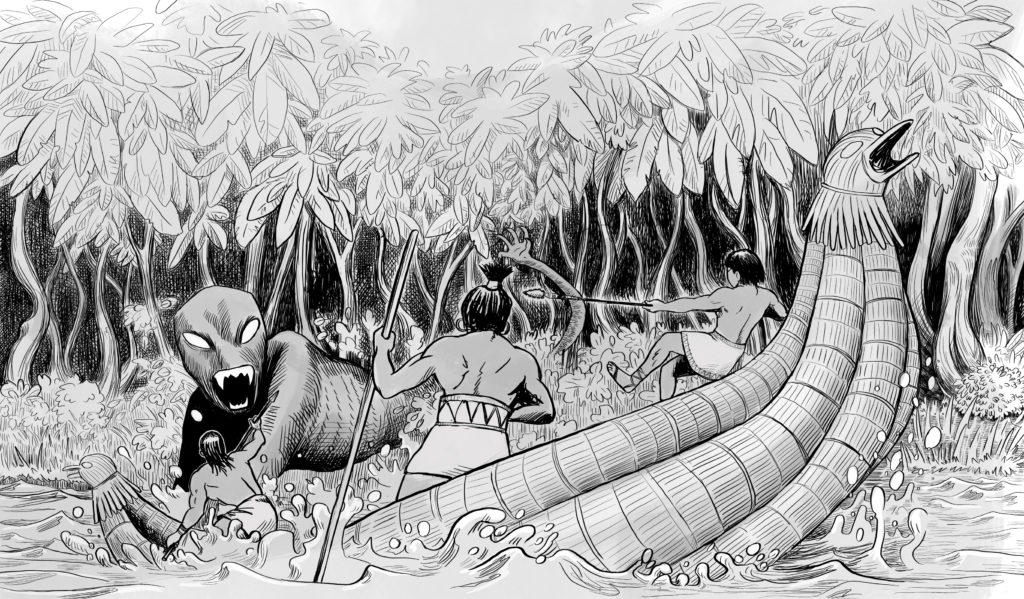

FATHER-OF-RIVERS, A TALE OF AZATLÁN, by Gregory Mele, artwork by Justin Pfiel.

Rain fell. As it had yesterday, as it would tomorrow.

“At least it’s a warm rain,” Kabil said with a wry grin, slipping his wide, straw hat from where it hung against his poncho-covered back, and settling it over his thinning hair.

“Why not wait a day, e’en two or three?” Nakia asked fretfully, worrying her lower lip between wide-spaced teeth. “The oysters will wait.”

Kabil snorted.

The rainforest provided many wonders for the people of Baak: bright feathers for their hair; medicinal herbs for their wounds; an endless variety of sweet and sour fruits; and when the hunters were successful, a host of birds, snakes, tapirs and monkeys for their belly. But most of their meat came from either the river, or trading with the tribal folk beyond the west bank who fished the far more capricious waters of the great bay to the north. But when Lord Hurakán hurled His wrathful storms against the Middle World, none dared venture onto the open waters, nor hunt in the thick forest. Then only Mama Kokoya’s waters provided.

In a particularly relentless Wet Season, like this year, it was dangerous to go too far upstream, where the fat trout, gar and carfish dwelt, leaving Baaki bellies dependent on old salt-fish or what could be caught by hugging the shore with drag nets and catch-cages: crabs, shrimp, and most of all, oysters. Oysters pickled and stewed, roasted, fried or baked; oysters made into soups and puddings; oysters for breakfast, dinner, and supper; oysters without limit. The early Wet Season was a hard time for sea-traders and sea-fishers, but for an oysterman, such as Kabil, it was the few moons each year when a fortune could be made.

“Don’t be an old woman,” Kabil said, with a wink and smile, stroking his wife’s chin affectionately. “I’ve trawled in far worse weather than this, and for far less profit.”

“I am an old woman,” Nakia protested, “and you, my love, are an old man, with swollen knuckles and knobby knees that hurt him all Wet Season long. You keep rowing on the river, when Mama Kokoya is swollen and angry and She’ll make me a widow.”

The oysterman laughed.

“La! My wife is become fisher and river-priest all in one! The local beds are fallow, but down-river is teeming. I’ve never seen so many rock-clams, either! Meat’s crap, but the shell-market loves them. If the Storm King keeps pounding our shores, I’ll need a second crew! Besides, men don’t fall off barges, my fretting fishwife.” Leaning down, he kissed his wife’s frowning mouth, and stroked her cheek with the back of one work-and-sun gnarled hand. “Mama Kokoya and I are old friends; I give Her blood, she feeds my traps. It’s a good arrangement. She’ll see me home safe.”

Those were the last words Nakia ever heard her husband speak.

***

The Wave-Serpent slid along the bloated and angry river, its banks hidden beneath the overflow – sluggish, muddy waters simply disappeared into the dense forest. The rains having passed – at least for now – the forest had come back to life. Along the shores, a plethora of river-birds contentedly raided the oyster beds; watching them feast was torture for the empty bellies of the sixty men on board.

At the stern, Sarrumos Koródu slumped wearily beside his first mate, who held the steering oar with the same grim determination a man might grasp a spear while confronting an angry cave-bear. They made a frightful pair. Sarrumos’s emerald eyes sagged, heavy from lack of sleep, and his thick, auburn hair was tangled in knots. His cloak of finely-woven llama wool was rumpled, sea-salt encrusted, and hung limply from the wide knot that kept it closed at his right shoulder. Dried spatters of blood-stained blue wool and coppery skin alike.

The mate, already a homely man with a short chin, long, slightly bulbous nose and pock-marked face, was no prettier for either the hastily applied stitches in the shaved scalp over his left ear. His already homely appearance was made ghoulish by the thick clots of dried blood darkening the scarlet-dyed fringe of hair that ran in a vertical stripe over the center of his head and down to his shoulders in the warrior fashion of the Hichitwa, a tribe of the far distant northern forests, where it was said the rain sometimes fell as ice. One of the hands clenching the long steering oar was badly bruised and swollen, making him wince each time he was forced to set-to with his entire body to keep the ship from drifting beam-on to the current. Glancing to his companion, the corner of the mate’s mouth twitched, as if fighting to suppress words.

It failed.

“Captain, the men have neither eaten for two days, nor drunk water since last night.”

“Nor have I. Nor you, Ollad,” Sarrumos answered. “They will endure, as must we all.”

“The Kokoya’s water is sweet, why not – “

“Is it, Ollad? How many villages have you seen along the river, these past two days?”

“None.”

“With good reason! There are precious few rivers above ground in Wahtēhmallán, even less whose water can be drunk. At the best of times, the Kokoya is a brackish fen for much of its length, with only the pretense of a current. Mostly, the southrons drink from wells and underground streams.

“Those rains came hard and fast off the sea; this water’s at least half-salt right now, and what isn’t salt is mud. We must travel a little further inland before we can refill our casks.”

“Then perhaps it is better to give them a drink from what remains, Captain, lest it turn ugly. Men will withstand many hardships in silence, but thirst is a relentless demon that maddens the mind.”

“Yes, it is,” Sarrumos agreed, his left hand rubbing his weary eyes. Blinking, he looked up and suddenly shifted his long, bronze sword in its crimson scabbard, bringing its hilt close to hand.

“Tzatlin—get back there!” he roared, hand slipping to sword hilt as he rose. The source of his anger, one of the corsairs, looking twice as wretched as the captain, halted in mid-stride towards the water cask. For a moment he stood still, eyes locked on his leader’s in defiance. Then, his eyes fell in defeat and he returned to the oar-bench, grumbling.

“Miserable bastard has lost his mind,” someone muttered.

“We’re going to die of thirst – on a fucking river,” another growled.

“Well, he needs to sleep sometime,” said a third.

Sarrumos sighed in resignation. This part of captaincy he could do without. Squaring his shoulders, he slid his sword free of its scabbard, filling his hand with an arm’s length of good, Naakali bronze. He pointed the blade at the discontent who’d made the implicit threat.

“Bring me that man!” he commanded,

There was no response, and for a moment, mutiny seemed imminent. Then Ollad had let go the steering oar and taken up his short bow, setting a copper-tipped arrow to its string. Four corsairs rose from their places and fell upon their fellow, dragging him out from his place amongst the benches and hustled him aft towards the raised half-deck at the tiller.

The malcontent glared up at Sarrumos. He was Chok Mayaabi by the look of him, as was most of the crew — dark-skinned, dark-eyed, with thick, straight black hair; half a head shorter than the captain, stockily built and more than a little bow-legged.

And there’s the problem. He could be any of them.

“Well, Che Maaj, what have you to say?” Sarrumos demanded.

“I’ve already said it,” the sailor answered defiantly. “You drive us up this river to our deaths. Better we stayed out in the bay.”

Sarrumos laughed, hand on hip, gesturing airily with his sword. It was a mirth he did not feel. As captain, he led by acclaim, bluster and, as he’d now remind them, sometimes fear.

“Think so? Then perhaps you should be captain – in which wise we’d all now be dead. If the storms hadn’t finished us, another Kaketzewáni patrol would have. Perhaps you’ve noticed, Che Maaj,” he asked, voice booming – his words were not for the sailor, but the entire crew, “that the princes of the Four Kingdoms grow increasingly anxious to be rid of us? That was not a patrol – that was a trio of military ships, actively hunting for corsairs. Hunting for us.”

Surrumos dropped lightly down to the main deck and lightly poked the corsair’s chest with his sword.

“Do you disagree?”

Che Maaj said nothing, merely glowered recalcitrantly.

“That’s a fine glare you have! I like it – it shows ferocity. But I wonder, Che Maaj, would those angry peepers have won us through that trap off the coast of K’ichecha? Would they have taken the salt haul from Itaapa or captured the kakao bound for Tukolatl? I think not.”

“That all means nothing if we die of thirst, while sitting on a gods-cursed river,” the man snarled. “We’ve survived misadventure after misadventure, Sarrumos – but we’ve only had those misadventures because the gods hate you!”

Somewhere a pair of cranes argued angrily over mussels. But on the Wave-Serpent’s deck, all had grown deathly still.

When, at last, Sarrumos spoke, his voice was soft, calm. Reasonable.

“It may be that they do. But let us see how well the river-gods love you.” Suddenly seizing the Chok Mayaabi sailor by topknot and arm, the captain spun, hurling the surprised man over the low rail, sending him sprawling headfirst into the Kokoya’s muddy waters.

Several of the men rose from their benches, angry words on their lips, only to stop, mid-motion as a copper-tipped arrow slammed into the bench between them. Others ran to the rail and made to throw a rope to their sputtering companion as the ship drifted past.

“Step away!” Sarrumos roared as Ollad took aim, fletched death already set to string. “Che Maaj has decided he is his own captain. A captain without a ship, as it seems.”

“He’ll drown!” someone called.

“He might at that,” the Naakali said with a false nonchalance. “But that is his own affair. Perhaps the gods’ as well. He’s no crewman of mine.” Turning from the rail, ignoring the sputtering sailor’s cries, he faced his men, handsome face turned hard, mouth set in a thin line. Atop the raised poop, Ollad had set another arrow to bow, daring any of the sailors to mutiny.

“Enough!” Sarrumos shouted. “You hunger, you thirst. I do too! But Baak lies ahead, a city whose Ix-Ajaw is my friend. Give me an afternoon of hard rowing, and I will crack the water cask wide. Row and drink. Or sit there glowering, and Gods Above bare witness, I will throw that barrel into the river, so Che Maaj can skiff on it out all the way out to Tzukábaal Bay. Which will it be?”

Thirty oars slid out through their ports and dipped into the muddy waters. Lowering his bow, Ollad turned back to the steering oar, watching Che Maaj, crying curses in three different languages, swim towards the thick-forested shore. The mate’s eyes met those of his captain, who watched after the swimmer.

“We leave him?”

For a moment, half a dozen different emotions passing behind those bright, jadeite eyes.

The moment passed.

“We’ll take the Serpent around that bend. If he proves determined to follow, we’ll haul him aboard.” Turning his head forward, Sarrumos urged the rowers on, his sword hilt beating time on the last water-cask. Satisfied, Ollad said nothing.

Behind them, Che Maaj splashed noisily towards the flooded shore. No one, not even the swimmer, noticed the long, misshapen black hands rising from the water.

***

The former crewman was barely lost from sight of their stern when they first spotted the fishing barge from the bow. An old, flat-bottomed craft used throughout Tehanuwak, it lay partly out of the water, wedged into the mud. The rope of her drag anchor dangled limply in the water, suggesting no weight hung below. Ordinarily, Sarrumos would have had them row past but he looked at the heavy nets dragging in the water, then back to his hungry, grumbling men.

“That’s an oysterman barge! One with full nets. That’s food, boys – and maybe water as well! Ollad, steer us close, but not onto the mud!”

Sheathing his sword, he moved between the rowers to the starboard bow, as the Wave-Serpent cautiously paddled towards it. Thoughts of food and water first on their mind, none of his crowd thought to ask why a fishing-barge should be run aground and abandoned. Or if they thought it, they did not give it voice, perhaps afraid their captain would turn the ship away.

As they drew near, oarsmen near the bow rose and used their oars to keep the galley’s beak from ramming into the mud, while Sarrumos himself lassoed the barge. “Pechotl,” he said, calling to a lanky Kaketzewáni, “choose two others and come with me. Ollad, hold the ship steady.”

Once they had tied off, the four men – Sarrumos, Pechotl and a pair of Chok Mayaabi – nimbly leapt the short distance onto the barge’s flat deck. Pechotl eyes fell first to the twin nets, still dragging heavily in the water. He licked his lips hungrily.

Sarrumos did not share his enthusiasm. First across, no sooner had he set foot on the barge than he was startled to see its boards were covered in large smears of drying blood, along with scattered clumps of human hair, matted in gore. A large clay cookpot that the fishermen would use when they came ashore, lay in a corner nearby, unharmed, but spattered in blood.

“On your guards, men!” the captain called, sliding his sword free of its scabbard. He heard the others gasp as they registered what lay before them.

“What happened here?” Pechotl gasped.

“Murder, most likely,” the Naakali captain replied quietly. He could hear men from the Wave-Serpent calling, demanding to know what was amiss. He held his left hand up, angled back at the crew, bidding them quiet, then gestured his fellow boarders forward. As they moved towards the small cabin at the barge’s rear, they saw that the floorboards were scored with deep gorges, as if made with the blade of a knife or sharp hatchet – or claws.

“Jaguar?”

“The great cats can swim, but they do not like the water,” Sarrumos said, crouching before one of the indentations, which was more than half-filled with blood. “It would not attack while the fishers were on the river. But something made these marks, and I do not think it was men. Whatever it was, it was none too gentle with its prey. Could a caiman do this?”

“No,” one of the Chok Mayaabi sailors replied, his voice soft, uncertain. “They pull their prey below, to twist and drown. Little blood. And—” he gestured to the gouges and shook his head.

“Let’s be away from this place,” Pechotl suggested, his hunger forgotten.

It was an excellent idea, but Sarrumos was having none of it. He dipped his finger in one of the deeper pools of gore. The rubbery skin on its surface broke, showing the blood below to be tacky, but still wet.

“The blood is not that dry, even with the air as steamy as it has been, this happened recently – a day or so. At most. Whatever caused this, may still be near – I want more answers before moving blindly upriver.”

Without waiting to see if he were accompanied, Sarrumos traced the wide, bloody smear, made as if dragging something large back to the cabin, a simple, peaked lean-to of tanned deer hide. Glancing in beneath the canopy to what he had expected to find an empty shelter, the Naakali captain let out a cry and leapt back, sword sliding swiftly into his hand. His move startled the sailors — Pechotl stepping forward with his spear, while one of the others stumbled half-way back towards the Wave-Serpent, before he even realized what he’d done. Paying them no mind, Sarrumos stepped forward again, and leaned forward, reaching in with his sword to prod…something.

“Captain?” one of the corsairs asked. “What is it?”

“An oysterman. A dead one,” he said it as if he were surprised.

“Was it a jaguar?” Pechotl asked, stepping closer.

“No…it was…he is unmarked.” Rising, he sheathed his sword. “Here, one of you help me drag him out into the light.”

The third sailor came forward and together, they crouched down beside the small shelter, reached in, and dragged its occupant forth. The corpse of a man, dressed in little more than woven rope sandals, loincloth, and short, cowl-like poncho, slid into view. Seeing that the corpse was neither horrific to behold, nor rising in unlife, the other two men pressed in closer.

Naturally coppery-brown skin had assumed death’s pallor, and the body had already gone through rigor and was relaxed once more. But there was neither sign nor scent of putrescence, confirming Sarrumos’s guess that no more than a day had passed. There was no blood that any could see, though some swelling and bruising at the throat. An empty knife sheath hung from a cord baldric, as did a water-gourd. The captain went to his knees at the dead man’s side and began inspecting the body.

“But, where did the blood – gods!” Pechotl gasped. He had seen what they all had. If the dead man’s flesh was not torn, that was not to say that his body was unviolated. A pair or dark, ragged holes lay where once there had been eyes.

“Gods? I think not. Demons? Perhaps,” Sarrumos said, dryly. “At least, of the human sort.” He continued to look the body over, lifting a limp hand. “The fingernails are gone. All of them.”

“The fingernails? Why?”

Sarrumos peered under the canopy, ducking hands and head inside as if searching for something. After a few moments he sat back on his heels, his right hand holding something jadeite, that fit in his palm, the left rubbing at the small, peaked auburn beard on his chin, as if trying to recall some lost knowledge. If so, he did not find it, and slipping the object within his tunic, he turned back to his men.

“Who’s to say what ugliness men will do to one another when their blood runs hot? Perhaps he was a rival in trade? Or in love? A cuckolded husband seeking revenge?”

“He seems old for that,” Pechotl argued.

“Then maybe an obstinate father, refusing a match?”

“That does not explain how he died,” the first Chok Mayaabi said.

“Drowning, I think,” Sarrumos said. “Probably held face down in the water.”

“And the blood?” Pechotl asked skeptically.

“A second oysterman, I suppose. One who went into the water, his body lost.” It was a reasonable, logical answer, yet it did not sit well, even as he proposed it. “Or perhaps –”

He never finished his thought, for just then a cry went out from the Wave-Serpent. He looked back to his galley and saw Ollad standing in the raised stern, pointing up-river.

“Canoes! Many of them, and their men dressed for war!”

***

“There are at least twenty of them in each of those boats,” Ollad said, scowling. His hand was on the steering oar, but his bow and quiver lay close to hand.

“God Above spit on me! I see two more, beyond, coming about the bend.”

He and the other men had hurried back the Wave-Serpent and the galley had cast off, leaving the gory barge and its slain crewman to drift on. Thirty oars struck the water, hard, seeking to pull away from the long, low-lying canoes, dug-outs carved from the trunk of a massive ceiba tree.

“Did you not say that Te’pekun and Baak are often at war?” Ollad asked.

“Yes,” said Sarrumos, beating his sword furiously on the water-cask. “And the River Folk tribes who dwell on the far bank are unpredictable and quick to take offense. But that is a lot of warriors for their villages to put out on the river unless the tribe is actively at war. In which case, gods alone know what we’ve sailed into.”

He recalled his last adventure along the Kokoya, invited on a raid by one of the River Folk’s shamans. It had not ended well.

They rowed steadily for half an hour, but the galley was heavy; the pursuers gained for a time, then fell back, then gained once more.

“We are pacing them, at least,” Ollad noted. Sarrumos, usually the more optimistic of the pair, was less cheered.

“Not for long. The River Folk are fresh, and if their crafts are built for the Kokoya at flood. They will follow until our rowers tire, or our prow drives into some mud bank hidden in the high water, at which point, they will swarm us like wolves taking down a wounded stag.”

“A grim prophecy.”

“Not prophecy. Knowledge. I’ve fought both with and against the River Folk and have seen them make war. Unless we reach Baak, our life’s journey ends. Keep her more in the midstream; we need the full force of the current to work against them.”

He resumed beating on the cask, and then, because the crew was obviously weakening, he sent Ollad down to give them drinks while he held the helm. They were tired, hungry and half dead of thirst, while their pursuers fresh. An obsidian arrow plunked into the wide steering oar, no more than a span from Sarrumoss hand, quivering in the polished wood.

“Ollad, our unwanted guests have arrived!”

The Hichitwa first mate made his way back to the helm and snatched up his bow. Pinching an arrow with thumb and finger, he drew back to his chin, sighted for just a moment, then fired. The arrow splashed into the water, well-short of the first canoe.

“My bow cannot match theirs for range, Captain.”

Sarrumos cursed, his eyes scanning between their pursuers and the river ahead. He heard long, bamboo bows firing, and the whistle of death in the air.

“Down!”

A dozen shafts fell around the galley’s rear. One grazed Ollad’s ear, another struck the raised stern, just short of Sarrumos’ head as he ducked down. A cry of pain went out from the rowing benches.

“Get it out!” a pirate cried, staring in horror at the arrow transfixing his hand to the oar.

Chancing being shot, Sarrumos stood tall in the stern and shouted out to his men, urging them on. “We race Lord Death Himself! Row harder! Row!”

More arrows swept into the crowded galley drawing blood as one man slumped, his neck transfixed; another screamed as an arrow dropped down into the top of his skull, razor-honed obsidian slicing easily through hair and scalp. But now, the attackers were drawing into Ollad’s range and there was an answering yell, as a warrior tumbled back among his paddlers, a shaft driven through his eye.

Dividing into two columns of two, with one remaining directly behind, the canoes began overtaking the Wave-Serpent on either side. The dugouts were simple, unseaworthy looking craft, but Sarrumos had learned to mock neither their efficacy, nor the speed and dexterity with which trained paddlers could maneuver them. In the bow and the stern of each boat men in jaguar skins and warpaint brandished small, wooden shields and obsidian-tipped spears, exposing themselves recklessly and dancing to attract attention. One to their port took an arrow deep into his thigh for his troubles, tumbling into the river.

“Pechotl, your bow,” Sarrumos cried, snatching up one of his own. “Kill the bravest, and perhaps we’ll slow their rush to board us.” He fired his first shaft at a canoe on their stern, missed, and shot again. But the gods were cruel, as often they are, and it passed between two paddlers to splash harmlessly into the river. A javelin thrown in rebuttal fell short.

“Look! Ahead of us,” Pechotl cried from the prow. “More boats!”

A moan of despair went through the men, made worse as more arrows whistled and hummed into the galley, finding flesh with a soft, wet thwap. One unlucky rower fell, howling with three shafts in him, all likely fatal, yet none anywhere that would kill him swiftly. Bracing a foot on the upsweeping tail of the stern, Ollad sent two arrows racing into the canoe in retaliation, then was forced to throw himself flat to avoid being cut down in return. As it was, he was clipped across the thigh, obsidian edge slicing deep through leggings and flesh.

Sarrumos dropped his bow and crouched down in the keel. Spying one of the galley’s earthen firepots, a new idea came to mind. Crawling to the pot, he began building and fanning the small flame that burned within. Once it burned steadily, he rose, swinging the pot by its chain, an arc of fire whistling about his head as the thick palm oil roared to life.

Letting the chain lose, he sent the firepot flying across the air towards the lead canoe. Fortunately, his throwing proved better than his archery, and the firepot smashed against the dugout’s edge, spilling its fuel on one of the paddlers, and then pouring within. The canoe began to drop back as some warriors sought to fight the fire, while others plunged overboard. Sarrumos smiled in satisfaction, then scrambled for his bow.

“They run,” Ollad called, firing another shot at one of the canoes, which had broken its pursuit and was turning back down-river. The dugouts, even the one still battling flame, were turning back as quickly as their paddlers could drive them, fleeing not their intended prey, but the dozen or so similar craft, bristling with armed men, rushing down-river towards them. Turning towards the newcomers, Sarrumos looked at the banner post with its spray of egret and fork-tail feathers, and sighed in relief, his shoulders slumping.

“Baak. They are warriors from Baak.” He had no more idea why a Baaki war-party was on the Kokoya then he did a River Folk one, but at the moment he was too relieved to care.

In less than a minute the galley was surrounded with long, long canoes, similar to those of the River Folk, though shaped more at the prow, and carved and painted so that brightly-colored animal faces, neither alligator nor caiman, but perhaps related to both, glided leeringly over the water. Chok Mayaabi war-cries whooped and howled across the air, and arrows sent an obsidian rain falling among the Wave-Serpent’s tormenters. For a moment it seemed the river would erupt in all-out battle, but then the Riverfolk canoes were turning, their rowers paddling swiftly back down-river in full retreat.

The largest of the Baaki vessels, more of a nobleman’s barge than a war-canoe, complete with carved rails and a brightly painted fabric awning, slowly glided towards them. She was paddled by slaves, leaving the warriors onboard free to fight with javelin, sword-club and bow. In the prow was a short man, even by Chok Mayaabi standards, muscular body swathed in a jaguar-skin cloak. Thick, black hair was drawn up in a warrior’s topknot, and his embroidered war-shirt, jade-encrusted pectoral collar, and the equally impressive pieces of jade and gold that decorated his nose, ears and lower lip proclaimed him a noble.

“Well-met once more, Sarrumos Koródu,” the newcomer said in the western Mayaabi dialect, holding his right arm aloft as the barge drew alongside.

“And to you Aapo Chaaj Kep, Jaguar and First Spear of Baak! Though how you knew to find us is a mystery.”

“There is no mystery – the gods willed it so! There is trouble on the river. The River Folk are in a rage; their war parties have attacked farmsteads from Baak to Te’pekun. It is the Ix-Ajaw’s will we turn the huntsmen to the hunted and send them slinking back to their villages.”

“What is your saying here in the south: ‘life and freedom is his who can keep them?’” Sarrumos answered. The jaguar warrior laughed at that, a deep, rumbling chuckle.

“That is true in all lands, I think. But yes, it seems this year the rains brought not only flood, but much anger and death. But not, it seems, for your or I this day, Sarrumos.”

He turned to one of his underlings, a dour-looking, one-eyed man whose nose looked to have been on the wrong end of any number of fights. “When the pursuers return, tell them to be sure that outlanders who crew it are given food and drink and treated as guests of the Ix-Ajaw. I will take Sarrumos and his man to Baak myself on the barge.”

“It would seem we are rescued,” Ollad said dryly, as he and Sarrumos gathered their things.

“I am remembered in Baak,” the captain said, breathing heavily, blood still pounding.

“And yet, we are rescued anyway.”

***

“Gods Below! Once we sail from here, I might never eat another oyster again,” Sarrumos Koródu pronounced, to no one in particular.

Glancing through the mead-house’s open door, Sarrumos gazed out on the river with a heavy heart. The windswept storms transformed Baak’s brightly white-washed homes into a grey and barren mass of stone, the tall, narrow step-pyramids at the city’s center looming ominously over all like monstrous sentinels. Frowning for the hundredth time that day, he looked with longing through the slanting rain, past the rows of moored and tarp-covered dugouts, to the low-roofed barns that held the kingdom’s finest vessels, the great ceiba-tree canoes that could easily sit fifty men, nearly the match for a Naakali galley. In that last shed was a real galley, his galley, now dry-docked and useless until the storms subsided.

With an audible sigh, Sarrumos shook his head and resumed polishing the sword that lay across his lap, anxious for something to fill his attention, beyond staring at the angry skies in a mixture of sullenness and impotent rage. The storms had kept them prisoners in Baak for over a ten-day and showed no signs of abating. The “Tranquil Palace of Welcomed Foreigners” in which he was lodged, was little more than a large, modestly maintained stone house comprising a dozen, austere guest rooms, a kitchen and a small garden, with servants to cook meals and launder clothes. It was enough, and far better than had been in the offering for his men. Common houses were rare in the southlands; most travelers either stayed with clan-relatives, or simply camped at night on public land beyond the city wall, which was no real option when the rains came.

He’d found a few beds-for-let scattered throughout the city for the Chok Maayabi members of his crew. The rest were living, unhappily, in the same warehouse that housed the Wave-Serpent, and Sarrumos had hired a disagreeable old fishwife and her sons to cook for them. He smiled at that, wondering how many of the sailors realized that he’d chosen her precisely because the only appealing thing about her was her beans and rice.

Fortunately, if the south lacked inns, men the world over liked to drink. There were numerous vendors selling both fine balché-mead and, if one were desperate enough, a passable palm-wine, and Sarrumos had become a connoisseur of them all. He didn’t particularly like the drinks on offer at this mead-house, but from here he could keep an eye on his ship – and her crew.

“Are you listening to me?”

The Naakali turned to look at his first mate and blinked, as if just seeing him for the first time. He smiled wryly.

“Not really, Ollad, no.” He looked to the bowl of half-eaten food lying before him and pushed it aside in disgust. “Have I mentioned yet how sick I am of oysters?”

“Every day, for more days then I have fingers. But as I said, Captain, we will have greater problems than oysters, if the storms do not abate.” Drawing on a lit pipe – the Chok Maayabi preferred to smoke their tobacco in sikar-rolls, but neither man had developed a taste for it – he blew smoke circles and offered it to his captain.

“I know. My purse grows thin covering the crew’s expenses, and Gods Below know that most of them have either drunk or fucked away their –”

“The men have no purpose and nothing to anticipate. They just sit. Sit and think… unwise thoughts.”

Sarrumos sighed in understanding. The Wave-Serpent’s crew were bold souls, but they were neither soldiers nor merchant-marines, and discipline was as alien to them as the power of flight. Left to sit idle, their hands and minds turned to dice, tiles, drinks and flesh, in no particular order beyond the more they drank, the less concern as to how they achieved indulging their other vices. Two mead-houses were now closed to them thanks to the drunken ramblings of Nopaltek, a mixed-race Naakali like himself, who’d managed to cause half a dozen fights in half as many days, before suddenly disappearing – likely murdered and, in the short time they had been here, with no end of people who might want him so. Taavi was nursing a lame hand, broken by Ollad’s war-club after he caught him thrusting it up a young maid’s skirt as she was trying to walk past him on the open street. Two days later, Sarrumos told him he’d geld him himself if he caught him eyeing their landlord’s young daughter again. Arguably, the threat had lost some of its effectiveness when he had to explain what a “gelding” was.

It would be a fair-sight easier for my crew not to be judged half-witted, violent scum, the captain thought grumpily, if most of them weren’t, indeed, half-witted, violent scum.

Putting his sword down on the woven petate-mat beside him, Sarrumos puffed on the offered pipe, then passed it back. “I know. We needs-be moving, before one of them does something truly stupid. I have been thinking to ask the Ix-Ajaw for a commission, perhaps –”

“Fine time for us to find you then, Captain!” a hearty voiced interrupted.

It was Aapo Chaaj Kep, but he was not alone. Besides the stocky little man was a lean fellow whose skin seemed so weather-beaten that he might be thirty-five or sixty. Swathed in a bright feather-cloak and adorned at neck, ankles and wrist with a collection of gold, jade, coral and polished bone trinkets, he seemed some sort of priest. The man was studying him so carefully, that Sarrumos felt like a turkey being appraised for his value as dinner.

“Does something in my semblance perplex you…Great One?”

“I was given to believe you were Naakali. But…”

“My mother was a Masetek concubine, but my father’s Naakali enough,” Sarrumos interrupted, not trying to disguise the bitterness in his voice. “Here in Wahtēmallan, I am a green-eyed, Naakali devil. In the Empire, I am a ‘brown-skinned runt’. Make of me what you will, but take me as I am.”

“Which is?” the priest asked mildly.

“Weary of banter. We have business?”

“We do,” Aapo Chaaj Kek interjected smoothly. “On behalf of the Ix-Ajaw herself.”

Sarrumos looked to Ollad, who said nothing, merely shrugged, and passed him back the pipe.

“I am honored Itzel Xac Kel has decided to remember me, and the service I once did her family.” Ollad winced. Insults about his paternity made the captain defensive, and when he was defensive, he could be … difficult.

The priest clucked his teeth. “Say rather, she has chosen to forget the slight you did the Princess Nauxika.”

“For which, we are all grateful, and reconciled,” Aapo hurriedly interrupted. He motioned to his cadaverous companion, “And this is Tajoom, Second Priest –”

“First Priest now,” the other interrupted. Aapo’s eyes flashed angrily, but he remained outwardly calm.

“Indeed. First Priest of Ah-Hulneb, Father-of-Rivers, and Kokoya his Daughter. It is in part, on the recent change in Tajoom-itzat’s status, that we come.” Tajoom nodded, a withered smile clinging to his narrow lips, dark eyes glittering like fine obsidian.

“There is a matter wherein we need your…possible…Naakali expertise.” He emphasized the word strangely.

Sarrumos puffed the pipe and smiled crookedly. “Even if I am a short, dark-skinned mongrel, eh? Alright, what is it you need advice on? If it is how to cast bronze, I’m afraid I have not the faintest idea. It’s copper and tin, which I’m told you don’t have a lick of, down here, and then you melt it all up in some combination…”

“It concerns a murder,” Tajoom interrupted.

“Several,” Aapo added, his voice growing soft.

They have him, now, Ollad thought sadly. Curiosity always has the better of him.

“And these murders concern me how, exactly?” he looked back and forth between the men, “or, for that matter, are worth priestly attention, because…?”

Tajoom shook his head. “These are not question to be answered in a mead-house. Come and see; tell us what you see. Then we will share what little we know.”

Passing the pipe to Ollad, Sarrumos rose to his feet, slipped his now brilliantly polished sword into its scabbard and slipped the baldric over his head. Ollad watched them leave, staring at the open door for a time once they were gone. Sighing, he began repacking his pipe.

He can’t help himself. Like a moth to flame.

***

Wahtēmallek cities were odd, rambling affairs, almost like a conglomeration of smaller settlements, united around a singular, orderly acropolis. Baak’s administrative heart was a tidy affair of stone palaces, temples and the sacred ball-court, ordered around a central plaza, all defended by a rather formidable, sloped stone wall, but surely no more than a thousand or so lived within the complex, which attached to a second plaza, less impressive than the first but twice its size, serving as grand market, meeting place and military training yard. A loose grid of paved streets held the homes of lesser nobles, merchants and artisans. Tucked behind the protections of a deep ditch, sloped, earthen ramparts and a low stone wall, the city’s urbane citizens took great pride in what, Sarrumos was told repeatedly, was the “real” Baak. Looking at the city’s defenses, the captain thought whichever was the “real” city, a single Naakali legion would make no more than a lazy afternoon’s work of conquering it.

But the city thrived on the hard labor of the common folk who dwelt beyond the protective walls, in a haphazard cluster of self-sufficient villages of packed-mud huts united to each other, and to the city-center, by raised, earthen roads. It was to such a village they walked now. Clinging tenaciously to the river it was comprised mostly of peasants working the fields watered by the annual flooding, and a sizeable community of fishermen.

Nobleman, priest and pirate made a strange fellowship, but less so than what greeted them as they reached the village outskirts. A cacophony of drumming, rattles, bull-roarers, and human wailing greeted their ears, well before they spied the mourners, perhaps a hundred or more, their faces painted white with heavy chia-paste, heads shrouded with dull, red shards, gathered in the village-center. One of Lord Death’s owl-priests danced about a bier upon which, even from here, a pair of bodies could be seen. Seeing them approach, some of the mourners fell silent, but others were lost in their laments.

Tajoom drew aside a sun-wizened man at the edge of the mourners. After a flurry of words, he slipped into the crowd and returned with an even more grizzled elder. Greetings were exchanged, and the tall priest gestured his companions over.

“Yeh, I found ‘em,” the fisherman was saying in Chok Mayaabi, his dialect and accent difficult for Sarrumos to follow. “I get to pullin’ up the nets like I do e’ery morn, ‘cep they won’ come. No. So, I says to myself it must be caugh’ on roots, or some big ri’er fish wha’s caught itself – which-wise, Mama Kokoya be smilin’ on me and mine for-sures.”

Tajoom nodded impatiently.

“But it was no fish,” he prompted.

“No! But I didn’ knows it yet, so I pull, and when it won’ come up, I get my sons, and together, we gets the nets up, and see there be two great, pale fish! But then I sees hair, and…” he paused, licking dry lips, eyes seeing into the past for a long moment. Then he looked up, eyes wide. “Then I sees a hand hanging through – a man’s hand. And the face…it’s Aakabe’s, only…only…” His voice trailed off.

Without so much as a word of comfort, Tajoom turned back to his companions.

“Shall we see what we have?”

Seeing himself dismissed, the fisherman slipped back into the circle of mourners, shaking his head. Trying to ignore the mourners’ hostile glares, Sarrumos passed through the crowd with his companions and moved to stand by the bier. He gazed down on the corpses and winced. The victims were young men, no more than their early twenties, though with their heads wrapped in red, funerary cloth to hold their jaws shut, faces painted with cinnabar, it was hard to say much more.

“What am I supposed to be seeing?” he asked his companions.

“Look more closely, to the hands and face,” Tajoom rasped.

He understood, even before he looked, and looking, his assumption was confirmed as he saw the deep scratches the red cinnabar chalk could not entirely hide. “It is like the skiff.”

“Yes. Their fingernails are also missing.”

“And, you bring me here to see this because…?”

Looking uncomfortable, Aapo Chaaj Kep held his hands up, shaking his head. “Let these folks mourn their dead, and we may speak as we walk. Come.” He gestured away from the bier, and they again slipped between the mourners, whose glared openly, but held their thoughts to themselves, clearly afraid to antagonize the mighty of Baak.

Walking out onto the causeway of raised earth and crushed gravel that linked the city’s scattered settlements, Sarrumos saw they were taking a different route back, heading towards the city’s political center. “Will either of you, tell me now, why it was important I see a pair of dead fishermen?”

“Soon enough,” Tajoom said, a small, half-grin curling his near-lipless mouth. The nobleman’s frown had only deepened as they walked, and Sarrumos’s sword-hand itched as he felt his pulse quicken. He reminded himself that he was armed, and the warrior and priest had come without any sort of retinue, an odd choice if they meant to take him captive.

Passing through a city gate, their destination was soon apparent: a pyramid, painted in aquamarine, brilliant green and deep blue, its base decorated in frescoes of river birds, eels, caiman and leaping fish. The temple stood as close to the river’s edge as the city wall allowed, with a large pool at the center of its own, walled courtyard. Between the piscine motifs and the way the acolytes bowed and scurried at Tajoom’s approach, Sarrumos presumed this was the divine house of Ah-Hulneb, Father-of-Rivers.

It was not to the steep-sided pyramid, but a side building, that the priest brought them; a priestly dormitory built as a single, long hall of cells. A pair of acolytes stood guard at the last of them, its entryway set at a right-angle to the others, nervously clutching spears that Sarrumos suspected they had little idea how to use. Seeing the First Priest, they bowed and stepped aside.

The chamber was large, a pair of rooms, rather than a simple cell, presumably the First Priest’s quarters. It also stank heavily of copal, sulfur, and death. Passing through an antechamber that seemed both study and sitting room, they came to a comfortable looking bedroom, but the sleeper who lay on the high-piled petate-mats would never rise again. Another corpse, this one bound in rich, red cotton shrouds, a heavy collar of silver, turquoise and jade adorning its shoulders, and a death-mask of leather covering the face.

“Your predecessor?” Sarrumos asked Tajoom, understanding now why Aapo had been slow to recognize the priest’s new status.

The other man nodded, “Kaján Tep, formerly First Priest of Ah-Hulneb.”

Stepping beside the dead First Priest, the Naakali lifted the funerary mask aside, knowing what he would find when gazing on the cinnabar-painted face below.

“The jewelers and gold smith will be summoned to make a proper mask, of course,” Tajoom said, wrinkling his long nose in distaste, whether at the twin gaping holes that stared accusingly up at them, or at the lack of proper funeral regalia, was unclear. “Once the Revered Voice of the Father-of-River’s death is made known.”

Gazing down at the sunken, cinnabar-painted face, Sarrumos wrinkled his nose and replaced the leather mask. He was not sure what charms or potions the temple used to maintain their revered ones until their elaborate funeral rites could be performed in full, but they were clearly not enough. “His body is far from fresh. When did this happen?”

“Three nights ago, while the Revered Father was performing evening rites.”

“Who was with him?”

“No one,” the First Priest replied. “The evening rite is generally performed alone. He was found by a servant, face down, in the reflecting pool. Including your oysterman and the two youths we just saw, that is seven dead. All taken on or near the river.” Cold, dark eyes met Sarrumos’s own, as one bony finger touched the side of his nose. “But perhaps you already knew this?”

Oh. Shit.

“Aapo Chaaj Kek – in the past I have done good service for Itzel Xac Kel, Ix-Ajaw of Baak. Am I here now to see these things as an advisor, or a prisoner?”

“That remains to be seen,” the First Priest said sourly, as he bent to adjust the corpse’s death-mask.

Aapo cleared his throat. “The Ix-Ajaw recalls my friend’s past deeds, and as such, bade me show you these things, and question you…discreetly.”

Sarrumos noted the nobleman’s choice of words. My friend, not her or our: he was indeed a suspect, and whatever sympathy or faith the commander of the queen’s Jaguars might feel, he should not count on royal favor.

“What exactly am I expected to know?”

Still fussing with his predecessor’s death-mask, Tajoom asked mildly over his shoulder, “Have you heard of an awiztol?”

Sarrumos looked perplexed. “Should I? The word – a name? – sounds Kaketzewáni.”

“Yes, I believe it is.” The First Priest stood and began straightening and adjusting his own regalia. “Masetek, as well. Those are the common folk of your Empire, hmm? A related people? Your mother’s people, I believe you said?”

“Indeed.”

Aapo Chaaj Kek’s face was a mixture of guilt and frustration. Duty won out, and the stocky man stood to his full, if unimpressive height, arms folded, broad chest puffed out.

“We are told that the name refers to a species of river or lake demon – one said to dwell in Lake Kulwakálko.”

“Lake Kulwakálko? But that’s in the Valley of Azatlán! We’re weeks away! What makes you say the killer is this…?”

“Awizotl,” the First Priest corrected. “And it is not we who say it, but one of your own men: Nopaltek, I believe he is…was called.”

“Nopaltek? He’s from the Valley, for certain, but…”

“Yes, and he seemed quite certain that oysterman was killed by his native lake monster; discussed it at length, in every mead-house along the river for days…”

“Before disappearing,” Sarrumos groaned.

“Coincidence, I am sure,” Tajoom said, lips curling into a smile far more predatory than reassuring.

“Sarrumos,” the jaguar warrior interjected, his face grim, “you were found, by your own admission, coming from a ghost-barge, its owner slain in a most terrible way. Since then, five more have been slain, six, if we count your man, including two of my own Jaguars, and Ah-Hulneb’s First Priest. The only thing that has changed in this entire time is…”

The corsair captain thought of the still missing Che Maaj, whom he had thrown overboard himself and winced guiltily. Was it seven? Or eight? “All that has changed is the Wave-Serpent’s arrival. You think I am behind these deaths?”

“In all cases, the dead were drowned, eyes and fingernails taken, otherwise unharmed – precisely as they are devoured by a creature said to dwell in the heart of the Naakali Empire,” Tajoom interjected in a calm, reasonable, yet oh-so-accusatory tone.

“I am no sorcerer! Besides, why would I do this?”

“You are a pirate,” the First Priest sneered. “Why not a sorcerer as well?”

Gobsmacked, the captain’s head snapped to face the jaguar warrior, but found less sympathy than he’d have hoped in Aapo Chaaj Kek’s broad face.

“You have reminded me twice today of the past service you have done for Baak and her queen. But…I am also reminded that those services also involved sorcery – sorcery that began with your arrival.”

“Aapo, you can’t possibly –”

“Two of my Jaguars are dead, and Baak has lost its First Priest – to a monster. Word will spread, and with it, panic! It needs to end, and quickly. You are not under arrest, Sarrumos, but nor, until the Ix-Ajaw decides, may you or your men leave Baak.”

From beside the dead priest’s bed, Tajoom’s narrow lips curled in just the hint of a smile.

***

The tenday of heavy rains had sunk village life into a virtual torpor, from which it was just now awaking. The small fishing canoes and oyster barges were still beached beneath wide, palmetto-leaf canopies, but a few of the older fisherman were there, inspecting them against damage as Sarrumos and Ollad appeared. One of the men spotted them, and called an alarm to his companions, hand slipping to the obsidian knife that hung from a cord about his neck.

“Why you come now, Outlanders?” the smallest, and seeming eldest, of the three demanded in the Trade Tongue. “Have we not dying enough?”

“Too much, Uncle,” Sarrumos said, hands held up placatingly. “Too much and Baak’s Mighty Ones does not enough to stop it. Give us that,” he pointed to one of the small, flat-bottomed skiffs, “and my friend and I will go and make an end of it.”

The knifeman spat, his eyes wide and wrathful. “You wan’ die, Outlander, do on your own! We not needs Mama Kokoya’s childer coming back for us!”

But the eldest looked thoughtful, chewing his lined lips like one might a particularly tough tobacco leaf. “You can do this? You know you can do this?”

“The gods alone can know, Uncle, but Ah-Hulneb has seen fit for this to come into my hands.” Reaching inside his tunic he slipped out a jade pendant that hung about his neck on silver chain. It was a twisting, spiraling figure, neither man nor serpent nor fish, but a portion of each, that looped about each other and swallowed its own tail.

For a long moment, all was quiet, the elder back to gnawing his lip thoughtfully. At last he pointed to one of the skiffs, the smallest and shabbiest of the little fleet. “Take it and go.”

Bowing, Sarrumos and Ollad uncovered the small skiff, and carried it down to the river, waddling awkwardly with it like a pair of over-sized ducks through the reeds to the bloated river. They felt the crushed stems twisting under their weight, mud squelching over sandals and between toes like some shapeless, yet living, thing. When the water reached the hem of Sarrumos’ kilt, he declared the skiff a float and climbed aboard, as Ollad used the long steering pole to push them further from shore.

They glided easily along the swollen river, its current carrying them northward, back to the thick mud-flat where they had found the dead oysterman. Ollad hugged the shore, the flooded waters too deep at the center for his pole. The breeze picked up, moist, clinging. Shortly thereafter, the drizzle began. The men pulled on the wide, reed hats they had purchased that morning, and prepared to, yet again, be wet.

“If the sky breaks, we could be swamped,” Ollad said, the mildness of his tone, belying the grimness of his words.

“Today, the rains are not my first concern.”

“Tell me again, why we are doing this alone, on little more than a raft, when we have a galley and men in the city, who sit, doing nothing?”

“Aapo Chaaj Kek’s friendship has its limits. His first duty is to Baak. He would never let us get the Wave-Serpent into the water.”

“But we do this for Baak. Why not bring he and his Jaguars to hunt the river demon?”

“Tajoom poison’s my name. He is First Priest of Ah-Hulneb, counselor to the Ix-Ajaw…and most likely the Awizotl’s master.” Jade and silver flashed in his hand as he held the pendant aloft. “This is the likeness of the Father-of-Rivers. Each priest wears one, apparently.”

“Then whose is that?”

“I do not know, I found it lying on the oysterman’s skiff, clenched in his hand as if he had torn it from a body.”

Ollad stopped poling.

“You are only now telling me this?”

His companion nodded his head sheepishly in agreement. “I am, at that. Apologies. But, more importantly, when I studied Kaján Tep’s corpse, it wore no such trinket. And thus, it were best to assume our new First Priest – who had much to gain with his predecessor’s death, and who is quick to label me a sorcerer, is at the heart of the matter.”

“But what reason would he have to continue sending the monster after his own people?”

“To conceal his real objective? Because he has lost control of the creature? I have no idea, Ollad, but whatever his reason, he has more motive than I! So, we go back to where it began, and put an end to it ourselves.”

Nodding grimly, the Hichitwa first mate began poling them forward once more. It was not long before they drew near their objective. Dead Kabil’s skiff was gone, even the gouges it left in the mud lost beneath the further-risen waters. A dark hump of mud still hovered just above the stream, the tips of water-logged reeds swaying about it. Sarrumos pointed, and Ollad poled them closer.

The rain fell harder now, little arrows steadily assaulting the water’s surface.

“How do you know it is here?” Ollad asked, voice little more than a whisper.

An obsidian-tipped harpoon held at the ready in his right hand, withhis left hand Sarrumos fingered the River God’s charm, holding it before him like a torch…or a beacon.

“It’s here,” he pointed with his weapon.

Something was gliding beneath the water towards the boat; something sleek and dark, like a massive otter, but with a long, wide tail. Whatever it was, the creature had slid from its den and taken the bait.

A pair of large, luminescent yellow eyes broke the surface of the water. There was something of both the reptile and the jungle cat about them, and they were large, at least the size of a jaguar’s. The eyes watched them, appraisingly, as one might regard a finely roasted turkey, before slipping beneath the surface once more.

“Get us to the mound, quickly,” Sarrumos said hurriedly, snatching up a second javelin in his other hand. “Let’s make it fight us on land.”

Ollad began poling more quickly, gliding the skiff skillfully towards the mud. They were a short throw away when the water rippled, parted; their little boat rocking with sudden violence. Sarrumos was nearly hurled over the side, into the water, towards those cunning, yellow eyes. Righting himself, he saw a large, ebon-hued hand, a strange six-fingered thing with a thumb on each end, rising over the back of the skiff, towards his mate. The captain lunged, thrusting down with his javelin into that strange, scaly appendage. The obsidian bit, sliced deep, drawing a red-black ichor that must serve the thing as blood.

The hand was gone, back over the side.

The skiff slid onto the mud-bank.

The water exploded around them.

All was chaos. A long monstrous skull, pantherine … canine … snapped out them. Sarrumos shouted and thrust his harpoon between short, snapping jaws, before being hurled to his back. Clawed hands snatched at him; they were mannish things, in the way a racoon or a monkey’s were, and there were more than a creature of four legs should posses. Gripping his spear, the captain thrust up, seeking a sleekly furred throat. Razor-sharp obsidian bit deep, dark ichor-blood splashed down onto him. A clawed hand lunged at his eyes, narrowly missed, and left bloody scratches along his scalp. Twisting the harpoon free, the Naakli thrust in again, deeper. Then the slavering jaws were at him, and Sarrumos was forced to wedge the javelin’s shaft between them, like a bit to which no reins were attached. The wood began to split…

But Ollad was there, thrusting the bargepole like a spear, ramming its blunt point behind heavy jaws with such force that the creature was knocked clear. Sarrumos rolled to his belly and tried to crawl free, but something caught his ankle, and with a great wrench, yanked him flat, then pulled him half into the water. He saw Ollad swinging the pole like a staff, striking something out of his field of vision, and a terrible realization struck the pirate captain:

There are more than one of them.

As his torso began to slide under the water, Sarrumos twisted onto his back, kicked out with a free foot, striking something hard, and then thrust his harpoon down into the muddy brown water, aiming again for the monster’s neck. The point sank deep, but the damaged shaft gave way, snapping with an audible crack. He reached for his sword, but a hand, corpse cold and terribly strong, grasped his right wrist. For a moment, man and submarine horror struggled, and then Sarrumos was dragged under. He heard Ollad calling his name, as his head disappeared beneath the surface.

Mama Kokoya’s waters were dark and cold; a wet, airless womb. Sarrumos’s lungs burned and his vision blurred as he fought to free himself. He had not had time to fill his lungs before he was pulled under.

Then, there was all the time in the world, as his vision went dark.

***

Sarrumos awoke, but for a time he was not sure if he still lived.

It was dark, cold, and he was soaked through. He could not see. There was nothing to hear, but he felt stone and muck beneath him. A sudden panic filled him, and he pawed in terror at his eyes, whimpering in relief to feel their presence. Thrusting his hands out blindly, Sarrumos found rough earthen walls through which something mossy and entangling – roots? – protruded. He tried to stand, was denied by a low roof of dirt and stone and dropped to his knees. His began breathing quickly.

Oh cruel, mocking Gods Below! He was under the earth.

Crocodiles and caimans were burrowers, making their dens in shallow caves beneath riverbanks. The monster, awizotl, they had called it, must do the same. In which case, like the great river reptiles, it must drag its prey home to dismember at its leisure.

No, that didn’t make sense. The other victims had been found whole, well, nearly so… he tried in vain not to think of those empty, unseeing eye sockets. Focus on being alive, he ordered himself. Focus on getting free.

Yes! If the awizotl could drag him under the water and into this den, then he could follow the same course out. He just had to understand which way out was. His hands moved about the dirt floor, seeking some clue, however small, and in time realized that in one direction the floor and walls were wetter, covered in a soft muck, whereas in the other, it was dried dirt. The muck led to the river, and hopefully, a short swim to freedom, before his lungs failed.

Stay. Calm.

Sarrumos crawled forward, the floor growing wetter almost immediately, until actual water began pooling about him, a finger or so deep. Then, in the darkness, his hand touched a pelt, sleek and oily like an otter’s. He scrambled back. Panic instantly filled his chest, his breathing grew ragged, the darkness overwhelming him, as he fumbled for the sword he still wore, though unsure how he could possibly wield it while blind and crawling.

Nothing came for him.

A seeming eternity passed in sightless stillness beneath the earth.

Finally, unable to stand it any longer, his breath quick and ragged in his own ears, his head pounding, as much from fear as the little cave’s foul air, Sarrumos thrust out with his sword. The keen bronze point struck something and pushed in. He might be blind, but he knew the feel when a sword thrust into a body. The Naakali drew the blade back and thrust again.

Silence.

Another thrust, just to be sure, and then he reached out to feel his blade. The bronze was wet, sticky, but the ichor on it was cool…as if thrusting into a corpse. Finally, he could take it no longer. His left hand reached out tentatively, and found a sleek, heavily muscled chest. The beast did not stir, nor did its chest move. It was not breathing. Lying in water about a hand deeper than the small pool he knelt in, its body filled the path before him. He pushed against the corpse, hard. The body shifted but moved little.

“This is your revenge for my killing you, eh? You’ve dragged me under, then died blocking my way free?”

Now what?

Well, the air was foul, but present, and clearly not fading. That meant, somehow, air was entering the den from the outside. Turning very slowly in the tight place, Sarrumos retreated from the dead ahwiztol, crawling through what he guessed was a mixture of silt and the scraps of prey. Perhaps there were small vents into the soil above — or better, another, landward entrance, like some sort of monstrous rabbit warren?

He was quickly disappointed. The tunnel shrank almost immediately and ended.

Squirming on his back, Sarrumos carefully slipped his sword free and, holding the hilt in his right hand, and blade in his left, used it like a pick to hack at the low ceiling above him. Dirt fell on his face. Crocodiles dug by thrusting their clawed forefeet deep into the mud and squirming backwards, dumping their excavations into the river. Ahwiztol must do something similar. Another pick sent a large clump collapsing onto his face and chest, making him hack and wheeze. The blade and sunk in half its length and revealed neither fresh air nor light. With the monster’s bulk filling the den, there was nowhere for Sarrumos to pile dirt save around his body, and having so little room, and no clear idea how far up he needed to tunnel, this was a good way to bury himself alive.

Mumbling a curse, which was the closest he had come in years to praying, Sarrumos slowly turned around himself once more, and began crawling back towards the dead awiztol. The monster was man-sized, not including that long tail he’d glimpsed in their battle, and likely heavier. While reasonably strong, Sarrumos would need to push it ahead of him while crawling on all fours; for how long, and in water how deep, he had no idea.

He hoped he could do so without drowning himself in the process.

***

Just as he was sure his lungs would fail him for the second time in one day, Sarrumos’s head broke the surface of the river. Gasping, he bobbed like a cork, slipped below the surface, then fought his way back up and greedily gulped in air. As he had guessed, he was not even a long javelin throw from the thick muddy mound, upon which the borrowed little skiff still perched, tossed on its side like a discarded toy.

Slowly, but with grim determination, Sarrumos pulled himself ashore and rose to his feet. He saw nothing of Ollad, but as he wearily trudged to the mound, he saw the soft mud was crossed with both human tracks, and many large handprints. The bargepole lay forgotten, one end trailing deep into the water. Was his friend and mate also trapped in some underwater den? Was he dead, a monstrosity feasting on his eyes?

Then he heard the pounding of snakeskin drums and the clashing of shell rattles echoing through the trees. Running to the skiff he looked within and found Ollad’s bow and quiver. Slipping both over his shoulder, he snatched up the bargepole and waded to the shore, slipping through the reeds as he followed the drumming’s call.

He was not sure precisely what he had expected, but it was not this.

A small crowd of men and, a handful of women, dressed in bark-cloth loincloths, paint and little more, knelt in supplication before what could only be called a slab of greenstone, a fortune in jade. Half as tall as a man, it was incised across its length with a single, massive glyph, encircled by many, smaller ones. He could not see it clearly in the twilight, but seeing the hints of a twisting, sinuous shape carved into the stone, Sarrumos guessed what manner of creature it was.

A tall post of skulls, human and beast alike, surmounted by what in life must have been a sizeable crocodile, stood near the altar stone; and tied to that post was Ollad. Before the bound Hichitwa, a figure swathed in an elaborate feather-cloak and tall headdress of blue-green heron feathers leapt and danced, shaking a rattle in one hand that he clashed periodically against the obsidian knife he held in the other, as he chanted. Sarrumos looked to his friend, to the bloody smears in the mud that stretched from post to the water, suggesting something heavy — say a man’s body — had been dragged, and made his decision.

The priest leapt, back arched, chanting falling short as an arrow sunk deeply into his back, a hand’s breath to the left of his spine. Stumbling, the man turned in surprise, his dark eyes registering pain and confusion, the latter mimicked in those of his attacker.

It was not Tajoom.

Seeking the jade pins that pierced his septum and bridge, the brilliant paint and heron-feathers that decorated face and limbs, Sarrumos doubted he was even Chok Mayaabi.

Riverfolk?

Right now, it did not matter.

A second arrow sped to its mark, burying itself in a naked, painted chest, upon which hung a large, jade pendant that was a match to that which hung upon Sarrumos’s own. The River Folk priest swayed, his lips moving soundlessly, then he fell to one knee, and toppled to his side.

Screams broke from the women in the crowd, while the men gaped at Sarrumos as if he were the avenging River God Himself.

For a moment, he may have been. He spotted a jaguar pelt, knew its wearer for a celebrated warrior and sent an arrow into his face, then another towards the groin of a man with a wicked-looking axe. It missed his groin but lodged deep in the thigh, and the man’s howls joined those of the women as the pandemonium spread, and the crowd began to flee in different directions. Slinging the bow, Sarrumos snatched up the long bargepole and swung it in circles about his head, clearing a path as he strode purposefully towards the altar. Two Rivermen, who had the look of acolytes more than warriors, stood beside Ollad, uncertain what to do as the mud and blood-spattered madman advanced. The first had a knee shattered for his indecision. The other decided – and fled.

A maguey-fiber cord passed through the crocodile skull’s eye sockets, binding Ollad’ s wrists high to the offertory post. Dropping the bargepole, Sarrumos drew his sword and sawed at the ropes. His eyes met those of his mate’s. Ollad smiled weekly.

“You are late,” he whispered through swollen and bloody lips.

“I took a nap,” The cords parted, and Sarrumos tore them from his friend’s wrists. The Hichitwa’s arms dropped and he briskly rubbed the life back into them.

“You woke up angry.”

“I usually do. We – “

His words died as an awiztol slithered ashore from the shuddering reeds to collect its prize.

The monster, for surely it was no natural thing, was black and sleek, like a great river otter, but its surprisingly long legs ended in all-too-human looking hands, tipped in ebon claws. The face was a horror, a short-muzzled concoction of otter, dog and wizened old man, with low, pointed ears angled back against its head – just as a dog might, before it attached. The eyes were reptilian and shone with a malevolent intelligence. But worst of all was the tail: long, sinuous, and covered not in fur, but in night-black scales, ending in a clawed, six-fingered hand that clenched and unclenched as it tracked his every movement. Sarrumos’s mind flashed to the bodies of Kabil the oysterman and the young victims whose funeral he had attended, he saw again the eyeless River Priest…and knew with horrid certainty what had the left the deep scratches as it gouged the eyes from their sockets.

Clear membranes drew across and back over slit-pupiled eyes that focused on Sarrumos. It hissed, a sound somewhere between a snake and a cat, but it did not approach.

Two more splashes of water: two other beasts, crawling out of the marsh. Their tail-hands clenched, unclenched in a swaying motion, as if seeking a path to the men’s eyes. Two handspans away, the awizotls stopped. Their eyes shone with the desire to drown, to rend, to maim. But they came no closer.

“Ollad,” the Naakali implored, “you should run!”

Ollad flexed his newly freed hands. Taking his bow and quiver from the captain, he set his back to the slab, and set nock to string. He looked down river, the waves washing to either side as the creatures clambered ashore. “They all watch you, Sarrumos.”

It was true, three pairs of luminescent eyes tracked his every move. Understanding dawned.

“Not me, this,” he held the jade amulet aloft. “Tajoom and the River Folk priest both wear such. I was wearing it when that monster dragged me under…”

Ollad, only half-listening, sent a shaft speeding towards one of the creatures, but it nimbly twisted aside, and the arrow passed into the reeds.

The creatures threw their heads back and howled. It was a terrible keening, like children wailing for their mother, only louder, more resonant. The reeds rippled, swayed, gave way as a long, dark head, nearly twice the size of its heralds’, emerged, dripping, from the Kokoya. The two men stood stock still in shock. Even the Riverfolk who had not fled stopped and stood silent, trembling.

The advancing awizotl gave a bellow louder than any twenty men might make and stalked towards them, its tail, half again the length of a tall man, reaching up over its back like a scorpion’s. Ollad fired his bow, thrice, and the great beast made no effort to evade. The first shaft shattered against its skull. The second struck, bit, but went unnoticed. Most terribly, the third was snatched from the air and snapped by that terrible, fifth hand on its scaly tail.

Meanwhile, the lesser awizotls continued to cry their weird exultations.

Sarrumos weighted the sword in his hand. The creatures were mortal, and his bronze sword was far larger and stronger than Ollad’s copper-tipped arrows. He was prepared to throw himself at the creature when he felt the amulet burn cold against his chest, pulsing with an inner heat and glow. Eyes alighting upon the altar stone, he saw it too, glowed from within. An idea came from him. Thrusting his sword into the earth, he ran to the stone.

“Keep drawing it towards us.”

Ollad glanced back over his shoulder, saw what his captain was about, and his eyes grew big. “You can’t move that! It weighs –”

“With this I can.” Sarrumos snatched up the bargepole, and wedged it in, under the altar stone. He pressed down hard, muscles straining, coppery skin flushing with exertion. Slowly, the stone shifted. Meanwhile, Ollad backed towards the stone, firing shafts at the creature’s eyes, which the tail-hand continued to bat away. It drew closer, jaws hinging open like a serpent’s, hooked and serrated teeth yawning wide, as if to swallow the world whole. Ollad sent a shaft, his second to last, speeding between those jaws to hit the purplish-black tongue within.

A roar filled Sarrumos’s ears, whether the beating of his own heart, or the awiztol bellowing over its pierced tongue, he could not say.

“Ollad! Jump!”

Many things happened at once, leaving Sarrumos afterwards with only an impression of events: the Hichitwa warrior springing aside; the awiztol lunging, a vast maw of hooked and serrated death; something tearing within him as he hurled the stone altar slab down onto the head of the nightmarish creature whose semblance it bore; a crash, like a mountain falling or Lord Hurakán’s thunder cracking, booming and echoing along the river.

Then time flowed normally once more and the great beast thrashed, its long tail cracking like a scale-covered whip. Ollad, already back on his feet, had snatched up Sarrumos’s sword and was plunging it again and again into the twitching body.

But Sarrumos himself did nothing. The abuse to which he had subjected mind and body these past hours at last claimed him, and he tumbled forward to the ground. As the great awiztol’s bellows faded, he heard the wet sounds of large bodies slithering into the river, and knew the children were abandoning their dying parent. As consciousness faded for the second time that day, the Naakali heard the familiar thump of a Hichitwa warclub resounding against a skull, and saw Ollad standing over the River Priest’s body with his own recovered weapon in his hands; the back of the old man’s skull bore a dent larger than a turkey egg, from which bloody bits of brain seeped free.

“Always best to be sure.”

***

“You are making a habit fighting monsters,” Aapo Chaaj Kek said with a wry smile, a lit sikar in his hand. He sat comfortably, legs folded over each other, warrior-fashion, besides Sarrumos’s who lay propped on cushions in his small chamber in the Tranquil Palace of Welcomed Foreigners. The Naakali felt neither tranquil, nor welcome. Mostly, he felt pain. Everywhere.

“It comes with being a sorcerer,” he said grumpily.

Aapo had the decency to wince in shame. “I do apologize, my friend, but Tajoom’s reasoning was –”

“Wrong?”

“I was going to say ‘sound’, but yes, as it turned out, wrong,” puffing on the sikar, he offered it to the other man, who wrinkled his nose in disgust. “Please know, I found it hard to believe.”

“That would have been great comfort as I was drowned for witchcraft.”

Another wince.

“How did you know where to find the monsters’ lair?”

“I didn’t. But the oysterman was the first known death, and I lost a sailor who fell into the river nearby,” he did not add how the man came to be in the river, “so I assumed a connection, at which point I realized that the mud-bank reminded me more than anything of a den. With few options and less time before I was hauled in, I decided to try my luck.”

“And lucky you were!”

Sarrumos gestured to the myriad of bandages covering scratches, bites and cracked ribs. “If you call this such.”

The Jaguar shrugged; a warrior was proud of his battle wounds. “There is word from Te’pekun – they too were hunted by the monsters. There, too, the attacks have now passed.”

“I can only guess that the intent was to bring the two cities to war, letting you do the River Folk’s killing for them. But why? Why are the tribes of the west bank so enraged?”

“Who can say? They are unpredictable savages.”

Propping himself up higher, the Naakali grunted as his battered muscles complained. He reached for his cup of spiced chokatl and decided the effort not worth it. “So all men say about people not their own. You might consider that they, and you, worship the same god, in the same guise – if the altar-stone I saw was any indication.”

“Bah!” Aapo Chaaj Kek said dismissively, as he passed his friend the cup, “I will leave such mysteries to the priests. Speaking of priests…be truthful: you went sneaking off, because you suspected beaky old Tajoom, didn’t you!”

Sarrumos sipped his chokatl, enjoying the sweet and spice playing about his tongue; about the only part of him that didn’t hurt. “I did.”

“Hah! Truth be told, I did too. He’s wanted to be First Priest for years, and Kaján Tep wouldn’t oblige him by dying!” Slapping his knees, the jaguar warrior rose to his feet. “But we judged the man unfairly. Ah, well, the gods will as They will.”

“That they do,” Sarrumos said mildly, looking thoughtful. He debated pointing out that not only did Chok Mayaabi and River Folk priests alike wear greenstone pendants adorned with the same image as the large stone he had seen in the woods…but once one had seen an awizotl, Father-of-Rivers’ carved likeness became decidedly, horrifically, less abstract. Tajoom had said the creature was unknown in Baak, but perhaps the many folk who dwelt along the Kokoya’s banks knew the awizotl well; had offered it sacrifices and veneration for countless generations, elevating a monster into a god.

He wondered what Tajoom would think of that bit of theogony, then wondered if he knew it already. He watched the stocky warrior move towards the belled curtains that served as a door, debating within himself about another realization he’d had in his convalescence. Better to keep quiet…

“Aapo. Before you go.”

The other man turned; head cocked in curiosity. “Yes?”

“Tajoom may not have called the monsters, that does not make him innocent.”

“What – exactly – are you saying?”

“The priest’s amulets kept the lesser awizotl from attacking. I saw none about Kaján Tep’s corpse when I examined him.”

“You think Tajoom took it so that the creatures would attack him?”

“I did at first, when I thought he had summoned the awizotl. But no – I think every priest of Ah-Hulneb knows what these creatures are, and what the amulet does, so he took it from the First Priest’s corpse and threw it in the river to make it seem so. Kaján Tep was found face down, drowned in the offering pool – as any murder who struck him from behind might do.”

“But the eyes –”

“Yes, the eyes. I saw the bodies, Aapo; I also saw firsthand how the creature claims its prize: with claws that leave deep scratches in their wake,” he gestured to his own bandages for emphasis. “There were no scratches on the First Priest’s face. They were taken with tools. Precise ones. Whatever – whoever – took his eyes –”

“Was a man.”

“You called me a monster-fighter. If so, then it is because I know this: the worst monsters are men. If you’d truly protect Baak, Aapo Chaaj Kek, tell the Ix-Ajaw to seek insider her own house, for the awizotl who dwells there in human form.”

Aapo was silent for a long time, his own eyes narrowed. Bowing his head, he turned, jaw-set in some unspoken determination, and strode from the room.

Sarrumos watched him go then slipped back against the cushion. Sipping his chokatl, he found it cooling near as quickly his desire to remain in Baak.

________________________________________

Gregory D. Mele has had a passion for sword & sorcery and historical fiction for most of his life.

An early love of dinosaurs led him to dragons, and from dragons…well, the rest should be

obvious. From Robin Hood to Conan, Elric to Aragorn, Captain Blood to King Arthur, if there

were swords being swung, he was probably reading it.

Since the late 90s, his passion has been the reconstruction and preservation of armizare, a martial

art developed over 600 years ago by the famed Italian master-at-arms Fiore dei Liberi, that

includes the use of the two-handed sword, spear, dagger, wrestling, poleaxe and armoured

combat. In the ensuing twenty years, he has become an internationally known teacher, researcher,

and author on the subject, via his work with the Chicago Swordplay Guild, which he founded in

1999, and Freelance Academy Press, a publisher in the fields of martial arts, arms and armour,

chivalry, historical arts and crafts