THE PASS

THE PASS, by Nick Mazolillo, art by Andrea Alemanno

Strand wasn’t afraid of what lay on the other side of the rope bridge. The opposite side of the canyon was a constant wall of fog. No one ever came from the veiled end of the crossing, and all those Strand and his father allowed to cross never once turned back. His first lesson was that the danger lay not on the other side of the bridge but within those who sought passage.

Payment to cross was a pound of pure moon gem but it was up to Father to deny or allow passage. Sometimes those who sought to cross were wrong, on the inside if not the outside; they were not evil but sullied with the essence of corruption. It was his ability to sense this corruption that put Strand’s father in charge. As apprentice, Strand was to learn all he could to one day guard the bridge himself. He hoped desperately that such a day did not draw near.

A few yards to the right of the bridge was their cabin, as cozy as it could be with two rooms and a wood stove. The land on their side of the bridge was black and of rock occasionally punctuated by scraggily, leafless trees; the branches of said trees only ever grew sickly yellow petals that, while foul tasting, were edible. The green of healthy, normal leaves and all the other bright colors were absent on their side of the bridge. Occasionally, sunlight trickled down from the ever-grey clouds above, but those occasions were as frequent as the full moon.

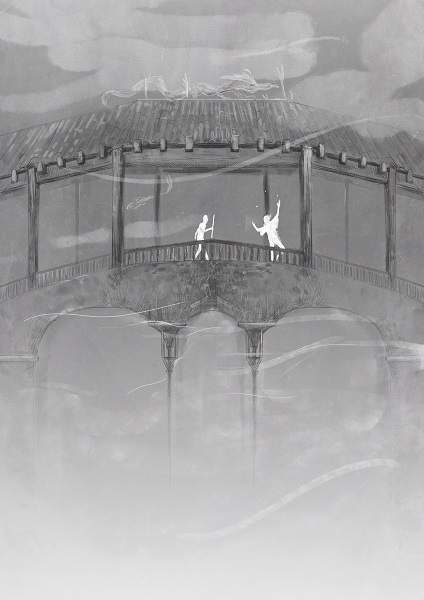

Most of Strand’s day was spent in front of the bridge, with he and his father often centered between the wooden totems where the web of rope forming the bridge spindled out from. The totems themselves were carved to resemble sullen giants’ faces with their mouths agape. Strand wielded a staff similar to that of Father, and when they were not dealing with those who wished to cross, they practiced combat.

In the eight months since Strand had been taken to the bridge to begin his training, he had since memorized Father’s moves. While he wasn’t as fast in his strikes, he was able to parry and counter, saving his face and limbs from the bruises Father had once covered him in when he first arrived. Despite his growing talent, Father warned him that one could not learn from only ever fighting a single opponent. Those who came to cross the bridge were as varied as the cultures of the world. Those who came to cross the bridge all came armed, and the warrior that now approached them was no exception.

The man’s leather armor sprawled around each of his limbs making him appear three-times as large. With each square plate flapping with his every step, there was an eastern touch to his wardrobe; he wore his long black hair in a bun and his twin swords sheathed over his back. Upon approaching Strand and Father, he removed a red face visor that resembled that of a permanently scowling demon with painted white tusks at the corner of its mouth. Beneath the visor was a clean shaven man whose scarred lips matched the scowl of his mask. The man looked from Strand to his father, and then drew one of his swords.

The steel of the blade glowed as if the sun were reflecting into it, despite the shadows that continuously clung to the ground on their side of the bridge.

“Halt and deliver us payment if you wish to pass,” Father commanded. If he was nervous, he did not show it. Lean, wiry and a good foot taller than Strand, he didn’t reek of fierceness. His grip on his staff remained loose; his eyes open and earnest. One of the first things the elder guardian had begun educating Strand on was the art of deception.

“What do you do need the gems for?” The warrior asked, holding his sword out like a torch. Elsewhere, he would have spoken a language they didn’t understand, but on their side of the bridge all spoke the same tongue. His words had a faint slur to them; the warrior was tired. His journey had been long.

Father stepped forward as if to embrace the warrior. This was a reassuring sign. “The gems merely prove to us that you are allowed to pass. Do you have them?” He asked. There was no hint of threat to his words but Strand knew it was there. He tightened his grip on his staff.

“Of course, of course. I went through a lot of trouble to acquire them but you know what they say about curiosity…” The warrior sheathed his sword, the blinding light of the blade leaving an afterglow in Strand’s eyes.

The warrior dropped to one knee and removed a travel sack from his hip. He undid the straps and a severed head nearly came tumbling out.

The torn flesh at the stump of the neck was pink yet bloodless. The head belonged to a young man around Strand’s age, his black hair trimmed to a short tuft unlike Strand’s own shaven head. The eyes flickered open as the warrior reached past the head and removed three moon gems that sparkled silver. Before the warrior could draw the sack closed, the head smiled and winked at Strand. The young guardian shivered. He’d seen worse in his months at the bridge yet he didn’t think he’d ever get as used to it as Father was.

The warrior marched to Father and thrust out his payment. Holding his staff upright with his dominant hand, Father took the gems. He didn’t need to inspect them; he’d already watched the way they glowed of their own accord the moment they were freed from the travel sack.

“You live here?” The warrior asked, eyeing their shack to the side of the bridge. “How can you stand the stench in the air?” He asked, his face wrinkling with contempt. Strand got the feeling that, elsewhere, this man was wealthy.

“Once you cross the bridge, you may not return,” Father recited the speech he gave to all those allowed to cross. “At one point in the mist you will see no land. Do not become confused on the direction you head in, or the bridge will hold you forever,” he said. The warrior’s response was to snort at him. Once he stepped onto the creaking planks that made up the rope bridge’s walkway, he drew his sword that captured the sun’s radiance. Strand always got a little nervous when travelers drew their weapons on the bridge, as if they were going to sever the ropes and destroy the passage to the other side. He couldn’t blame them, though. Only a fool would wander into the fog without his weapon ready. Strand watched the warrior disappear into the mist, and when he finally looked away he saw his father toss the moon gems into the canyon where they would disappear into the mist below like fallen stars absorbed by the earth. The older man then turned and was solely concerned about the path ahead of them, ready for the next would-be crosser.

Days often passed between crossers, but the grey light of their world never faded. Father was the keeper of time and he was the one who told Strand when it was time for dinner and rest. A natural stream flowed less than a quarter mile away, its water splashing off as a little waterfall into the canyon below. In addition to the foul-smelling yellow flowers they picked that budded from the trees around them, Strand and Father took turns scaling the sides of the canyon ridge. A hairless species of purple-skinned bat often burrowed in the little holes along the cliff face, and while they had a painful bite, they were easy enough to grab and strangle. They weren’t as boney as they looked, and with the help of a precious bin of spices Father had stowed in the cabin, an import from the other side of the bridge, the flying mammals weren’t entirely unappetizing.

The bottom of the canyon was as veiled as the far side of the bridge, but it felt closer somehow. When Strand crawled along the ridge, he always felt as though he could go a little lower; a little further. The mist at the bottom of the canyon seemed to writhe and flow, as if it were really a sea with all sorts of treasures buried beneath its waves that made moon gems pale in comparison.

That day they encountered a warrior with a head in a sack would be the first time they encountered two crossers in the span of a single day. They should have known it was a harbinger of something terrible, but part of being a guardian of the bridge was focusing on the current moment and the current threat only.

They heard the second crosser of the day before they saw him, from beyond the bridge the land sloped into hills and bluffs. The path to the bridge, if it could even be called such a thing, was made of ash that stood out on the black rock and soil; the path itself was as winding and as twisted as the landscape At first Strand thought it was the crosser’s armor that creaked and groaned with every step before he came into view over the rise of the ridge in the distance.

Strand tried to not let it bother him when he realized the crosser’s skin had rotted away in places; through the torn gaps in the crosser’s armor was the blackened bone of exposed skeleton. The undead man dragged a broken spear behind him, its rusted metal tip the cause of one of the grating sounds, the rest of the noise coming from the man’s grinding bones themselves.

“Halt,” the guardian said. Strand could already tell; this creature would not be allowed to cross. Sometimes crossers came who appeared dead, who bore horrific wounds and were drenched in blood, but there was always a spark of life to them, a sign of the desperation that drove a person to keep on going just a little further. The thing that limped toward them was little more than a windup toy, striving toward them on a mission that it has long forgotten the purpose of.

“You have come the wrong way. Turn back now,” Father told it, not bothering to ask for gems.

The undead man came to a stop. The spear dragging behind him did not rise.

“I am sorry,” Father said, which surprised Strand; it was off script. He had never before shown compassion for those who came to cross.

The undead man’s face was half obscured by a helmet that tilted over his eyes. His nose appeared to be of flesh along with that of his top lip, but from his bottom lip to his chin was exposed bone and teeth. The lips did not move as he gazed up at Strand’s father.

“You must go.” The order came again. The undead man waited a moment after that command before silently turning, dragging his spear along the rocks as he creaked back the way he had come. Despite not uttering a word, Strand got the sense that the undead man had wanted to tell them something. Unlike the other walking corpses and abominations that were denied entry, he’d stared at Father instead of the bridge; he’d shown no intention of crossing at all.

Many nights later, while tucked into his cot with his staff by his side, Strand awoke to the sound of a cat meowing. Father sat by the door, his staff standing straight between his hunched up knees. The meow came again and Strand realized he hadn’t seen or heard a cat, nor any other domestic animal, since he came to train at the bridge.

“Is it a crosser?” Strand asked.

Father shrugged and Strand went to their cottage’s one window. A trio of dark shadows made their way across the bridge.

“Should we stop them?” Strand asked and Father sighed.

“They cross on their own. As do the scarabs and the flies and on the rarest occasion, a black hound.”

“Father, I don’t understand.” Strand had never heard of animals crossing the bridge. Once, a winged man had flown overhead. He’d waved down at Strand and his father before vanishing into the mist over the bridge. They’d then heard his wretched screams that began up in the air before trailing all the way down to the bottom of the ravine.

“The lords of this realm are troubled. The felines go forth to the other side as emissaries. There will be those who wish to cross that we cannot allow to pass. You think yourself ready?”

While moon gems were the standard currency to cross, there were some creatures that could be adorned in the things and Father would still not let them pass. Such creatures were abominations in the form of man; part of Strand’s apprenticeship was learning to identify them and turn them away if they insisted on crossing.

“I hope so,” Strand said. Father laughed.

“I believe you’re ready. Do you remember the words you must recite?”

“I’m surprised I don’t say them in my sleep,” Strand said.

“You will sound the part,” Father began. He looked over Strand’s shaven head, the way he gripped his staff and how his newly sculpted muscles bulged. “You will look the part, too” he added.

“We must hasten your training. The next one who comes to cross will be yours to confront. I fear your time to learn with me grows short. Soon, you will have to learn for yourself. ”

“I’ll do my best,” Strand said, and he’d seen his father fight those wished to force their way across. Once, a giant man covered in furs and wearing a crown of yellow flowers had insisted that he did not know of the moon gem fee to cross the bridge. Strand screamed and shivered every time his father managed to reflect the stone with his staff, sure with each blow that the staff would eventually snap in half, leaving the older man defenseless. Finally Father had struck the giant man in the throat, crushing his windpipe and causing him to fall to his knees where he slowly choked to death. Father had then demanded Strand’s help tossing the giant’s corpse into the canyon.

Father often let would be crossers live if they gave him a choice. Once, a woman with knotted, golden hair and several nooses hanging from her belt had told them that her moon gems had been stolen from her by a winged demon. She’d nearly worked one of those nooses around Father’s neck before he’d crushed her toes with the edge of his staff and then broken her jaw. She’d slunk away only to return a week later, hollow eyed, covered in fresh cuts; from the look of her ribs visible beneath her skin she’d likely not eaten in the time since their last encounter. The woman with golden hair had returned with moon gems. Father acted as though the two of them hadn’t met before, and upon reciting his speech and accepting payment, had allowed her to pass. She spat at Father’s feet but for that, he had no reaction nor comment. He did not watch her cross the bridge. He fixed his eyes on the path before them, in search of more crossers.

“You must act as if I am not with you. I will remain by the hearth when they come,” Father said. There was no room for Strand to offer his opinion on the matter. He’d learned better than that after his first week of being reunited with Father. Their side of the bridge was not meant for relaxation or fun. The world he knew and cherished so well was at stake. To guard the bridge was to keep chaos of the abyss and the simplicity of light in the utmost balance.

The next crosser arrived following three days of constant sparring between Strand and Father. The mock fighting was too comfortable. Father’s strikes weren’t as hard as they were when Strand first arrived. Strand hoped it was because he’d gotten stronger, and while that was possibly true, he wondered if it was also because of love. When he’d first arrived, he hadn’t seen his father in nearly three years; it had just been Strand, his sister, and his mother back where the food was sweet and you could feel the warmth of the sun. Now, after getting to know one another again, the aging man’s staff striking across his arms and chest no longer stung. Strand hoped Father was as skilled a tutor as he was a guardian.

Father was with Strand when they heard the crosser. They heard singing coming from over the black hills in the distance, and before Strand could comment on the strangely squeaky voice, the cottage door was closing behind Father. The test had begun.

Strand sighed and turned to face the path, staff held in front of him. He closed his eyes and envisioned what Father looked like, alert but with his posture on the verge of being welcoming; if another man had been guardian there would have been more confrontations and more bloodshed. Strand loosened his grip on his staff, took a deep breath and then slowly released it. He’d seen many horrors in his time at the bridge. What rose up over the hill seemed to have been sent for him personally.

His family had been together when he was a boy. They lived in a cabin by a river in a village called Endymion. On summer nights, the village children would gather by the great community fire where the elders would tell them stories. There were tales of bravery and trickery, of the underworld and the gods and how mankind came to be. On occasion, the children were told stories meant to frighten them. One such story concerned a creature called the Abarimon; a forest demon with backwards facing feet that would confuse hunters after it stole little children away. Strand had shut his eyes during the telling of that tale and imagined how his parents would have felt, thinking they followed the trail of their son’s abductor only for him to be carried away in the opposite direction. The thing that rose up over the hill had its black robes drawn up to its knees and, barefoot, Strand got a glimpse of pale feet facing in the wrong direction, the bend of the creature’s legs like that of an inverted goat’s.

The robes gave way to a Jester’s hat with three rings dangling from the cloth; the creature’s face was done up in black and white paint, the white bordering its eyes and mouth. Its exposed hands were as pale as its misshaped legs, which in turn were almost as white as the makeup. The creature’s voice was almost feminine as it and seemed to dance to and fro, from one edge of the ash path to the other.

Strand took a single long blink and focused. Many demons tried to cross the bridge. This one was just uglier than most. He hadn’t ever heard of a creature of legend trying to cross before, but in some parts of the world, Strand knew, the fabled bridge and is constant guardian was believed to be a myth as well.

“Halt!” Strand called, and upon hearing his voice, the Abarimon jester took a bow. What Strand had assumed was the bunching up of the creature’s robes was actually some sort of growth along the thing’s back.

“I have your payment, no fear my noble keeper of bridges!” The jester raised a pale finger in the air; Strand noted how thick and sharp the fingernail appeared to be. Whether the things nails were naturally that way or filed, they were a weapon. Strand became grateful for the length of his staff.

“You,” Strand began but the creature cut him off by raising that same white finger to its own lips. It pulled what at first glance appeared to be three moon gems from the folds of its robe. That was problematic. Strand knew he couldn’t let it cross. It was worse than some undead thing. It was a mockery of humanity that even the gods from all corners of the earth and beyond would frown upon. How would Father handle this?

The jester began juggling the moon gems, humming as it did so, slowly edging closer and closer to Strand and the mouth of the bridge.

“Stop!” Strand commanded but ever so slightly, there was a crack in his voice. The jester’s eyes widened at the sound of weakness, its irises flashing silver.

“Certainly!” The Jester’s voice warbled as it came to a stop, rocking back and forth on its backwards legs like a flicked spring. It continued to juggle the gems, tossing them into the air so fast the three crystals seemed to morph into five. “Oops!” The Jester called and Strand couldn’t help but flinch as a gem sailed past his head and over the side of the cliff

“Darn!” The Jester called again, sending another gem past Strand’s head and into the ravine. Again, Strand flinched. If he lost his composure, he lost his ability to deceive. If the Jester could see how scared he was, it would use that fear to make him weak. His father had told him the key to winning a fight was to seize every opportunity presented to you; the duality of that advice, he had said, was that your smartest opponents followed the same advice.

“Leave here, now!” Strand commanded, and finally his voice was strong; his words felt as though they were flung from the center of his chest. The Jester laughed and chucked the final moon gem over Strand’s head. He watched it fly, and in doing so he forgot Father’s advice; never let your eye off the crosser. By the time Strand looked to the Jester once more, the mad thing was only a few feet away, its mouth drooping open and its clawed hands raised.

Just before impact, Strand lifted his staff. He didn’t have time to jab forward as the Jester ran into him, the point of the staff sticking under the mad thing’s ribs. The Jester didn’t react, its claws swiping across Strand’s face, slicing free a ribbon of blood as the thing’s nails dug into his cheek. Strand used the staff to twist the Jester around and then pushed it away. Rapidly he struck it in the side of the head and then the kneecap, only its knees were inverted and his staff swung through empty space.

Strand jabbed his staff at the Jester’s midsection in an attempt to ward it back, and the cackling thing grabbed it, trying to tear it from his hands. It pulled him forward, let go, and using his own momentum dug its claws into Strand’s breast. A hiss of pain burst through Strand’s lips as he swung the end of the staff into the side of the Jester’s head. It should’ve been stunned and knocked onto its backside, but it merely laughed. Strand got his bearings. The Jester’s back was to the bridge, it had maneuvered itself around him. It had tricked him into exposing the one thing he was meant to defend.

Out of the corner of his eye, Strand watched the entrance to his father’s cottage. Strand was losing. The true guardian of the bridge had to come out. The test was over.

“You were going to drop them over the side anyway!” The Jester said. “I did it for you! Payment received and down the, uh, cliff,” the Jester made an exaggerated gulping sound and giggled once more.

“Payment not accepted. You must go. I deny your passage,” Strand said through gritted teeth, not sparing a moment to feel the lacerations in his flesh.

“I don’t agree,” The Jester said, shrugging its hands into the air as it began walking backwards onto the bridge; facing and taunting Strand all the while.

“I said leave!” Strand screamed before leveled his staff and charging.

With one of its backwards feet already onto the boardwalk of the bridge, the Jester remained absolutely still until Strand was just about to strike. Sensing something was wrong, that the attack would be countered despite the perfect, upward arc of his staff, Strand tried to pull back. The Jester thrust its head down and the bit the staff in mid-air, his mouth extending like that of a serpent to be twice the size of a normal man’s. Strand tugged at the staff but it wouldn’t budge. Despite the Jester’s teeth being sunken into the wood, the Jester laughed. It raised both hands and grabbed at the staff, tearing it from Strand’s grasp. The Jester straightened itself, admiring Strand’s former weapon.

“The craftsmanship is impeccable,” the Jester admired, and then launched the staff at Strand like a spear. He tried to duck, but the Jester accounted for that. The lead side of the staff struck him in the nose and for a moment, Strand went blind as he sank to his knees. The staff lay across his feet as he fumbled for it, blood gushing all over his hands. When Strand looked up, blinking away tears, he saw the Jester vanishing through the mist as the entity crossed the bridge.

Strand screamed, leaping to his feet to charge after the cackling abomination. A staff swatted out in front of Strand, pushing him back. Father stood by his side, a sad smile on his face.

“We can’t let him cross over! He can’t be let loose there!” Strand pleaded but Father merely shook his head. Strand’s nose was broken, he sounded weak.

“You must compose yourself. This is the cost of failure. It will grow bored of waiting for you and cross, soon. Many innocents will perish, mostly children. Eventually it will meet its end as even the hottest of flames eventually extinguish.”

“But we can stop it, we can go after it,” Strand pleaded but his father raised a hand.

“And who will look after the bridge? Who will keep that abomination’s equally wicked brethren out?”

“You could have helped me! You could have stopped it! Those lives are on your hands!”

“I know. I chose you as an apprentice,” Father said, and those words may as well have been another staff strike to the head. Strand let loose a whoosh of breath and found it hard to inhale again, his mangled nose throwing off his ability to breathe. .

“Know that I would not choose any other. This was the only way you could learn. I failed in the past, and now you have failed in the present. I have not failed since, and I have faith you will not fail again. You will be better aware next time, I am sure of it.” Father clasped Strand’s arm; he was numb. He no longer felt his wounds

“Your time here grows short. You will return home soon. Your mother is waiting for you.”

“I can’t tell her what happened. What I’ve allowed…” Strand felt like sobbing, but he couldn’t do that in front of Father. The next time he laid down for bed, perhaps, with the blankets pulled up around his face.

“You must tell her. Your training does not end when you leave me here,” Father smiled, and pointed to the bridge. “That thing will be out there, now. You’ve seen its feet. You know how to follow the tracks. It will kill, but if you find it in time, it will not kill many.”

Strand looked to the bridge, the only path back home to the realm of the living. “May I go now then, father?” Strand asked and his father nodded. Wiping the blood from his face, he and his father clasped one another’s arms and touched foreheads.

“I will await your return. You will learn much in your hunt, your lessons are far from over, but I believe you will be successful. I have taught you all I can. For now, this is my bridge. One day it will be yours.”

“Until that day,” Strand said, and then he left his father without looking back. He didn’t need to look over his shoulder. In the land of the dead, everything would be as he left it.

________________________________________

Nick Manzolillo is the author of the Lovecraftian horror novel Moon, Regardless. His short

fiction has appeared in over sixty publications, including: Switchblade, TQR, Red Room

Magazine, Grievous Angel, and The Tales To Terrify podcast. He has an MFA in Creative and

Professional Writing from Western Connecticut State University. Currently, he lives in

Rhode Island with his wife and two well-read cats.

Andrea Alemanno is a compulsive illustrator who fills the line spacing, preferably at 300 dpi.

She’s from Italy and loves to move into a new city searching for inspiration. In every city, she constantly keeps drawing.

Now, 3 decades later (and a little bit more), she is still drawing and learning something new everyday.

She loves the traditional touch into a digital tools world so uses pencil, ink and digital colors to give life to her artwork.

Sometimes she shares her knowledge with wannabe illustrators.

Her work has been selected for several awards and she’s currently working for Italian and international publishers.