HEART OF VENGEANCE

HEART OF VENGEANCE, A Tale of Azatlán, by Gregory D. Mele, artwork by Justin Pfeil, audio by Karen Bovenmyer

Jaakhár was in flames, the ancient palace-complex engulfed in a red, vengeful glow that gleamed evilly in the blackness of night.

Helomon Twelve-Vulture, now Lord of the Red Flower Clan, reined in his foaming, winded horse, wheeled about, and looked back as the conflagration consumed both his birthright and his hopes. The drumming beat of pursuing hooves had faded, but few and halting were those loyal warriors who had kept faith in his flight. Wiping at sweat — surely it was not tears — with the back of a blood and dirt-streaked hand, he sheathed his badly nicked, bronze blade and turned to face his warband’s pathetic remains.

Betrayal was still new to him; so, as Helomon looked at the slouching men seated atop bone-weary beasts, the grim expression he wore looked almost comical on a young face more used to laughter than tears. Looking from the roaring flames, to the weary warriors and back, Helomon’s lips pressed hard together. He was young, but no fool; these were broken men.

The captain of the guard looked to his lord, feeling his dark eyes upon them. For a long moment, they stared at one another, eye to eye, and then the guardsman looked away, having found a sudden interest in his horse’s reins.

“You are clear of the palace, Great One…”

His hoarse voice cracked and trailed off, but its implications were not lost on the young lord. “You? Not we? Is there more you wish to say to me?”

The aging soldier sucked in his breath and chewed at his lip like a beast worrying an open wound. Then, his shoulders fell, and the words came out all at once. “All the southlands march to Kulkos’ banner. We…you…bade us stand loyal to Azatlán, and so we have …”

“As have I! What more can true men do when a thief seeks to steal their Lord’s throne?”

“Of course, Great One, of course. But, e’en when the rest of the Red Flower turned to the Lord Kulk…the Usurper’s…standard, we stood by you. We fought. We bled. But the Great Speaker has not come. Azatlán has not come. We are wounded and weary, our chariots broken and abandoned, our horses stumbling beneath us,” he flung an arm behind him, “Look at them, Great One. Bowstrings frayed; arrows nearly gone. Our armor is dented and our swords dull.”

Helomon narrowed his eyes, his scowl deepening. “Your swords, Captain? Or your spirits?”

There was a shifting of weary horses, and a stirring of haggard men, the clinking of bronze armour, and the creak of leather. Eventually, unable to endure the silence, the captain spoke.

“Where will you go, Helomon-tzin?” he muttered. “The south is fallen, and all is in your enemies’ hands. Your own kin now carry the Usurper’s banner and call for your death.”

“You failed to mention that my cousin will pay in good, southern gold, for my head,” Helomon said softly, mockingly. There was a rasp of metal and leather, and bloodied bronze flashed in the moonlight. “Perhaps, you’d care to take it with you?”

The weary old soldier neither paled nor flushed, merely hung his head as he twitched his horse’s reins. “Lord Hatûm’s holy light guide you, Great One; and Bloody-Handed Tuwâs give strength to your sword.”

Watching his men desert, the bitterness in Helomon’s heart erupted into a mirthless laugh. Lifting his nocked blade high in a salute, he held it aloft until the sullen, broken men had retreated down the hill and out of his sight. Once they were gone, the young lord slammed the sword sharply into its scabbard. He sat fuming astride his horse, watching the retreating figures. But as the last of them disappeared, he felt the wrath-fire die within him, keenly aware he was alone. The captain was right, where in the Nine Hells could he go?

“The Red Flower ceases to bloom,” he lamented, “the blood of its Heroes thinned to water by time’s passing. Gods be praised my father did not live to see it.”

“Not so thin. I see a Naakali lord, proud in his anger, and twenty men afraid to try and take him for a fortune in traitors’ gold,” came a soft, melodious voice from the night’s shadows.

With a curse, Helomon wheeled his horse about, his sword leaping to his hand.

Death, or rather one of His brides, stood watching him.

At first, she seemed a disembodied skull, a horrid wraith floating in the night. But then he saw she was mortal, or at least wore mortal woman’s form, her face merely painted in a skull’s semblance, her body shrouded against the damp night air by a light cloak of black cotton, trimmed in embroidered glyphs of silver thread, and held closed at her breast by a perfectly normal-looking hand. Looking at the garland of white flowers she wore as a chaplet, constraining long waves of raven-black hair, his heart ceased its pounding.

A priestess of Xokolatl, Lord Death. However odd her presence, or grim her deity, she was still no hungry ghost come from beyond the Borderlands to devour his soul.

Seeing him relax, the point of his sword ever so slightly lowering, the priestess smiled. No doubt, she meant it to be reassuring, but with her face painted in a death-mask, the expression was ghastly.

“All is not lost, Helomon-tzin. There is still vengeance.”

Vengeance. The thought flamed in his weary brain.

“I thought Lord Xokolatl did not concern Himself in the politics of men.”

She smiled again, her teeth as white in the rising moonlight as any bleached skull’s. “Indeed, He does not. Nor does his priestess. But she is also Anukhepa, the woman whose family dwelt in Jaakhár, and is thus as susceptible to desire vengeance as any other.

Anukhepa. An ancient Naakali name. Was she a clanswoman? He did not recall an Anukhepa, but there were other noble families in Jaakhár. At least, among those who had turned traitor.

“Name me your pursuers. Your betrayers,” the skull-faced woman spoke. Her voice had a sibilant, breathy huskiness.

Helomon’s sword lowered, and he spoke softly, recounting them each in turn, his own voice sharp with impotent rage. “Xanthas Khol… Akareu Four-Reed…Gayán of Draxos…Nadros the Lion…Tzaampos Nine-Serpent…my kinfolk, all of them.”

He completed the litany of traitors and Anukhepa was studying him, her piercing, green eyes staring like burning emeralds from darkened pits. In that instant, she seemed again Death’s own avatar, and he forgot for a moment that he was Helomon Twelve-Vulture, now Lord of Jaakhár.

“You have their names, Anukhepa. Can give me vengeance?

“No,” she said, stepping towards him. Reaching out, her cloak fell open to reveal a lithe figure, coppery skin naked but for woven sandals and a kilt-like skirt of the same funerary cloth as her cloak, further adorned with heavy arm rings and a wide collar of the red-copper metal sacred to Lord Death. She held her hand up towards him, as if offering it to a fearful child. “But I can bring you to one who can.”

“Where would you have me go? What allies would we find? The Great Speaker is in the far north, driving back the barbarians, while First Spear Kodoras leads Azatlán’s legions south and east against the Usurper.”

Anukhepa gestured toward the ominous red glow of looted Jaakhár, “Far from here. North and east, to Lord Xokolatl’s holy city.”

Helomon laughed grimly at that.

“Koltopek? The City of the Dead? Even should we slip this noose, it is a ten-day or more away, and my horse is half-dead under me. He’ll never carry us both”

Anukhepa shook her head, her hand still outstretched to him.

“Even as my Lord led me to you, He shall lead us to safety. Take me astride, Helomon-tzin and this horse shall carry us to Koltopek …and vengeance.”

Vengeance.

Did it matter where Anukhepa led, so long as there was retribution at its end?

He took her hand, soft and oddly cool, and then she was mounted behind him, wiry-strong arms wrapped about his waist. Helomon gathered his weary horse, and they began descending over the hills into the black desolation of a war-torn land.

II

Their passage was strange, less for the danger they faced, than for its absence.

Tehanuwak was a warm land with only two seasons — Wet and Dry — and they were well into the latter, with its hot air and arid breezes. Yet the air that first night grew thick, and patches of mist seemed to find their path time and again in the days that followed. Helomon asked his companion if the mist was her doing, but she shook her head.

“I am no witch; whatever mysteries happen, do so because the god wills it, not I.”

On the fifth day, as they stopped to rest, Helomon’s horse stumbled, sank to its knees, struggled to rise and failed. Crawling beside it, the priestess lay her head upon its shuddering breast. Stroking the foam-flecked muzzle, she chanted softly in the Old Speech.

“The earth is a grave

which nothing escapes;

nothing is so perfect,

that it does not descend to its tomb.”

Thinking her words were a final benediction for his dying mount, Helomon went to one knee, and drew his knife, ready to offer blood for the beast’s parting. Rising, he was about to cut its throat when the horse snorted, shook its massive head and staggered to its feet. He turned questioning eyes to Anukhepa, whose shoulders slumped, and head hung low.

“He will see us to Koltopek,” she said softly, still kneeling. Head lowered, she rose wearily to her feet, and climbed onto the horse’s striped back.

Helomon again wondered at the strange young woman who had come to him out of the darkness. They had found a stream to bathe in on the second day. He had washed away the dried blood, not all of it foemen’s, that clung to his hair and skin; she the blotched and smeared cerement paint. Beneath the grinning skull face, she was younger than he might have guessed and attractive — no beauty, but strong featured with a certain aloof sensuality that he supposed was fitting for one who served the Keeper of the Final Secret.

As for secrets, Anukhepa kept plenty of her own, and it was an effort to draw anything out of her. Eventually, he learned that she was a member of the Obsidian Owl Clan, whose Jaakhári branch had been all-but exterminated in the city’s fall; it existed at all only because she herself still lived. Although not noble, the Obsidian Owl was a very old Naakali clan, whose members worked as apothecaries and embalmers, and sent a fair number of its second sons and daughters to serve the Tomb Lord’s temple. When he asked why only the second-born entered the temple, she smiled wryly.

“Any less in the birth order would be disrespectful to the god, of course.”

“Understood. But why not the first born? If not the eldest son, then the daughter?”

“Has Helomon-tzin known many of Lord Death’s priests?”

“Before you? Not really, no.”

“Has he known any whom were married? Heard of any?”

“Oh… I…did not realize. I knew that a number of priesthoods demand their clerics be chaste, but…”

She shook her head and laughed, that melodious, low chuckle that seemed more mockery than humor. “I said nothing about chastity! The Lord of Tombs cares not for where, how or with whom His chosen take their pleasure, so long as we build no attachments to the living world: No marriages, no children, no adoption contracts or inheritances.”

“Ah. I see now.”

Indeed, feeling the priestess’s arms wrapped about his waist, head resting against his shoulder, keenly aware of her pressing against him, he saw that he was twenty-four years old, and still had much to learn about the world.

They rode in silence.

III

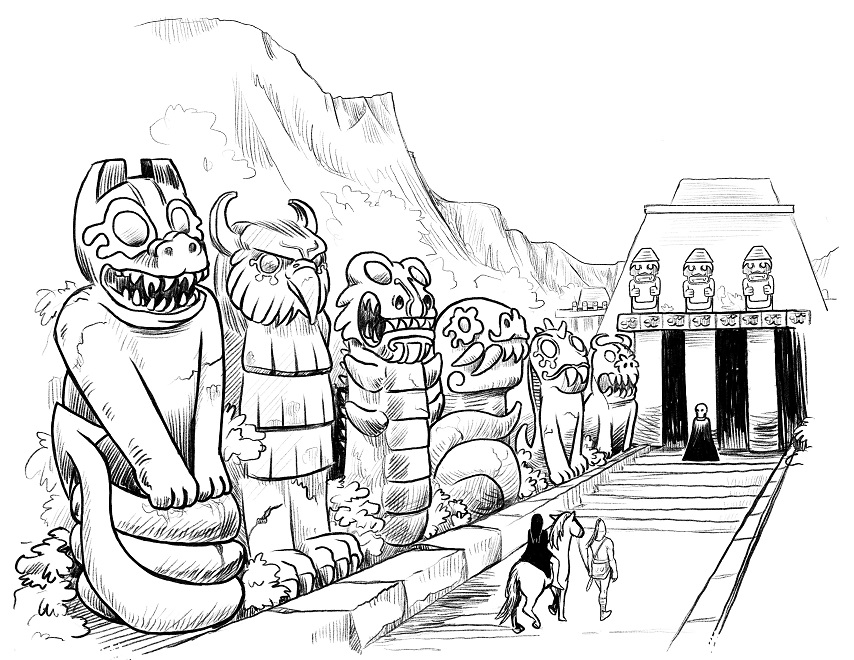

Koltopek was a city of tombs; a royal fellowship of death founded in the time of the Godborn invaders, amongst whom only the Great Speaker of Azatlán was now deemed estimable enough to dwell. At the center of those half-buried tombs and ancient monuments sat Death’s temple, built in three broad terraces of sandy-red stone set against a half circle of cliffs like a vast sepulchral heart nestled against jagged ribs.

At Anukhepa’s urging, Helomon led their horse through the necropolis gates and along the dusty sphinx-lined road that passed through its center and up the sloping stone causeway; a long ramp, carved with leering images of Underworld demons and capering skeletons, rising two stories to the temple’s vast, colonnaded entrance on the middle terrace. As they passed through the columns, the young lord struggled not to gape at the towering friezes and reliefs. This was a royal tomb built beyond all mortal scope; a monumental mortuary palace built to honor Death Himself.

As they reached the ramp’s summit, Anukhepa slid from the stallion’s striped back and strode to the towering, bronze-studded, double doors that stood open before them. Crossing her arms over her breast, she knelt on one knee, saluting an old man in a long, sleeveless robe, who stepped forth from the shadowed adytum beyond. She spoke, and he answered, in the all-but forgotten Godborn language. Helomon only dimly understood; the Old Speech was the language of priests and sorcerers. He was neither.

Whatever words passed between them, the old man waved Helomon forward, making him as welcome as any living man could be in the House of Death. Servants came to take his horse’s reins, but as they reached for the animal, it fell to the earth without so much as a final breath. Eyes wide, the young man stared in horror at his fallen mount; its flanks rapidly sinking inward, hide cracking and peeling, stomach bloating until it had the look of a kill left for days beneath the Dry Season sun.

He spun accusatorily to Anukhepa who knelt beside the dead animal and kissed its forehead, between filmy, unseeing eyes.

“I told you he would carry us this far.”

Mind reeling with the realization he had spent nearly a ten-day riding on a dead steed, Helomon was still gaping when more servants appeared to lead him inside the temple, gently promising fresh water and oil to wash away the filth of the journey, as a parent might offer a sweet to turn a child away from a street beggar. Numbly, he let them lead him on, looking back over his shoulder at the horse’s rotting corpse, and the young woman standing beside it.

Anukhepa felt his eyes upon her and looked up, promising with a small smile that she would see him when they “spoke to Sipan-tzin, Lord Death’s Speaker”. They had been together for every moment of the last nine days, and although the priestess was fey and inscrutable, Helomon found himself unwilling to leave her. But, remembering his station, the young noble made no protest, only nodded his head in agreement.

Soon, the dust and grime were washed away, his legs and arms anointed with palm oil, and a pair of skull-faced acolytes leading him deeper into the temple for his audience with its high priest. Riches aplenty might be buried in Koltopek’s many tombs, but the temple’s halls were as austere as the lonely god it honored. Only the outer shrine, which was their destination, showed any ostentation, its walls covered with elaborate, painted murals of the deceased’s journey to the afterlife. In the hall’s center was a massive, basalt statue of Lord Death sitting upon His terrible throne of human bones. There was no altar before the statue, merely a copper offering bowl, for alone of all the Empire’s many gods, Xokolatl demanded no sacrifices. He needed none; in the end, all came into His sterile kingdom.

Sitting upon a small dais before the idol was a man of late middle years, who Helomon assumed to be Lord Death’s Speaker. If so, the high priest — Sipan they had named him — was dressed little differently than his subordinates: Leather sandals, a pleated black kilt beneath an open, sleeveless robe of fine, red cotton and a painted and bejeweled, leather pectoral collar. His face was not even adorned with the white chia paste Anukhepa had worn when they first met, and which, as she knelt dutifully before the statue of her divine “husband,” he saw she had now donned once more. Freshly bathed and dressed in a white loincloth and copper jewelry, her cloak had now been replaced with the carefully painted semblance of bones decorating the entirety of her otherwise naked body, itself grown thin, bony over their journey and privation, leaving precious little to be seen of the mortal woman with whom Helomon had journeyed.

Priest and priestess had been speaking when the young noble entered, and their voices trailed away as he drew near. With apprehension, Helomon noted that Anukhepa would not meet his gaze.

The high priest shifted his gaze from the young woman’s face and regarded Helomon, with penetrating, dark brown eyes set deep in a craggy, dark-skinned face stretched tightly over high cheekbones and a hawkish beak of a nose. The nobleman’s eyes widened. The priest was of the Maize Folk – a man of the conquered tribes that dwelt as helots within the Empire. It was rare for such a man to rise so high among the all-too-xenophobic Naakali. The priest’s nation made little difference to Helomon, however. In these last weeks he had been betrayed by Naakali of the highest pedigree and rescued by a determined band of Maize Folk servants, who had died to the man helping him escape, while his own soldiers had abandoned him. The lesson was learned; from now on, he judged all by their own deeds, and nothing more.

Kicking off his sandals, the young lord knelt before the older priest and bowed his head to the ground. “All glory be to Lord Xokolatl, Master of the Black Wind, and to Sipan, His Speaker.”

“Lord Death has heard your entreaty, Helomon Twelve-Vulture of the Red Flower Clan. Your words have lit an ember in His dead heart. The Underworld shall give you that vengeance which the gods Above have denied. As the Black Wind blows, so shall you overtake your enemies, one by one, and the death you meet to them in the world of men shall be but a glimpse of the torments that await them before the Throne of Bones. You will hunt with Lord Death as your hound, and while you hunt, neither bronze nor obsidian, famine nor fire, can harm you.”

Hearing Sipan’s pronouncement, Helomon’s heart pounded in his chest. He fell to his knees and kissed the bones embroidered on the hem of the high priest’s cotton robes. Looking up, he opened his mouth to speak —

“Wait!” the old man said, holding a bony hand aloft. “Xokolatl is called ‘Final Arbiter’, not ‘Boundless Mercy.’ Nothing the Underworld offers is given without a price. The Grave Lord shall grant you the power to hunt your enemies to ground. All, that is, save one.”

Helomon’s mouth fell open in confusion. His eyes turned to Anukhepa and saw her confusion as well.

“Xanthas Khol. He who profits most by your death; he whose betrayal most fills your mouth with ash. That one you may not have and live,” the high priest said. “Let him be and you will live; seek his life, and the last vengeance you shall not see. The choice is yours.”

“But…I…why?” Helomon sputtered. “Why grant me all, but he who matters most?”

“More than any god, Helomon Twelve-Vulture, Lord Xokolatl understands betrayal. When the gods made war, Xokolatl’s divine brothers and sisters abandoned Him in the Underworld; there is little place in His dead heart for love or compassion. You have received a small portion of what little remains. He gives you your revenge, but if you would have it all, then you must be prepared to lose all, to lose the world of life and love, as did the god Himself.”

“And Anukhepa? What of her? Her folk died in Jaakhár’s fall; it is by her counsel and her aid that I stand here now. Surely, Lord Death would see His own bride avenged?”

Sipan straightened his age-sloped shoulders and his eyes flashed angrily. “Do not judge a god by mortal standards! When the Sisters of the Grave come to our Lord’s service, they leave all mortal attachments behind; trading the bridal wreathe for grave flowers, a mother’s veil for a burial shroud. Anukhepa’s deeds bespeak of blasphemy—as well she knew! She would work through you to gain a vengeance that duty to the god denies her? Then so be it: Should you choose the path of blood, Lord Death’s wills that the woman Anukhepa goes beside you, with His blessing, but not as His priestess. Her place here is at an end. Marry your fate to Death and take His bride as your own! Only know that her womb is as sterile as our god’s kingdom.”

Helomon’s eyes shifted to catch Anukhepa’s. He saw that her coppery skin had become nearly as pale as the painted bones that decorated it. She trembled slightly, her white teeth chewing nervously at her lower lip. Whether by Underworld magic, or mortal cunning, she had led him here, both to claim his vengeance and her own. But even Death’s brides were apparently not exempt from His terrible bargains. To avenge her kin, she must rely on Helomon’s willingness to die; to see the vengeance carried to the end, she must give away her place among Xokolatl’s chosen.

The young lord realized they stood at the crossroads of destiny. He could be a bestower of mercy or the architect of doom — for them all. He felt crushed beneath the weight of a responsibility best reserved for gods, not men.

Then emerald eyes met his, and she smiled, not wryly, not grimly, but with the bright light a young woman shines to reassure a young man. The turquoise and jade pendants hanging from her ears chimed softly as she slowly nodded her head.

Helomon turned back to the priest. Weighing his fate against the seeming numberless, unavenged dead, he paused but a moment, then spoke with grim certainty.

“The choice is no choice at all, Sipan-tzin. It is Xanthas Khol who stands at the center of all that has transpired. Without vengeance on him, the rest matters not. Lord Death’s price shall be paid.”

The old man sighed and nodded wearily.

“Then rest here, in Death’s arms, Helomon Twelve-Vulture, and sleep the sleep of the dead. For in the morning, you return to the world of the living, and become the hand of the Underworld’s justice.”

IV

Helomon came to Koltopek a supplicant but went forth as the avatar of Lord Death’s vengeance. One by one he hunted his enemies down, and with each hunt his wrath became more terrible to behold.

He rode with Azatlán’s conquering legions when Kulkos the Usurper was broken at the gates of the holy city of Hochulan, and his loyalty was well-rewarded: Among those taken captive was Tzaampos Nine-Serpent. As his fellow nobles were led away by priests for offering on the Sun King’s altar, Tzaampos was thrust, naked and stumbling, towards a gilded war-chariot, in which his young clan-chief stood, dressed in his full war-panoply, the Red Flower war-banner fluttering from a long spear. Tzaampos struggled and cursed as they pierced the hollows behind his heels and passed thick cords through them, securing him to the war-cart’s axle. Curses turned to pleading, and pleading turned to screams when the chariot-team began to run. It was said that for many hours after the sun had set, the red ruin of his body twitched and moaned where it was left to rot in the open field.

Gayán of Draxos also fought for the Usurper but when it was clear the Fates had turned against them, he fled to the walls of Na Yxim, and for a time was as safe as any man can be when trapped in a besieged city. Three months later, the city fell, and Gayán’s hide was nailed to the gate of the Red Flower clanhouse.

Nadros the Lion was not flayed, at least, not directly. He had awarded himself that epithet in celebration of a youthful hunt, when, alone, he had taken one of the great cats unawares. Now, dressed in the torn remains of that pelt, his skin lashed raw with thorns, he was prodded by spears and shot at with arrows towards a small pride, who watched him with first curiosity, and then with hunger. The hunter became the hunted, but not for very long.

Akareu Four-Reed was craftier, and had long-since fled, a fugitive of Imperial justice. His flight gained him three more years of life, before his angry kinsman found him hiding in the mountainous kingdom of Tzantzutzwányu, far to the southwest. There was none present but the tall, death-raven of a woman who was Helomon’s constant companion to see what form his vengeance took, but rumors whispered that it was the most terrible of all.

One by one he had ridden them down; all but Xanthas Khol. For years Helomon followed any rumor of his uncle’s son, pursuing him across both the Empire and the chaotic borders of the southern city-states to which he had fled. But always, Xanthas Khol eluded him. As the trail grew old, Anukhepa whispered in Helomon’s ear: Had they not had their revenge on the others? Did not the dead of Jaakhár sleep quietly now in the lavish tombs he had raised? Had not the Red Flower’s lord proved his loyalty to true Great Speaker of Azatlán through tireless service, in both war and peace?

When Helomon remained unmoved, she threw her arms about him and wept. Did he not remember old Sipan’s words, that only in death would he have vengeance upon his cousin? Did he mean to leave her, and all they had won, so soon?

Never had Anukhepa sought to turn his hand or temper his revenge; never had she shown the slightest weakness or sought to alter his course. Seeing her now on her knees, her arms about his legs, tears soaking into his kilt as she pled her case, Helomon was powerless to deny her. Thus, he let his vengeance slumber, and vowed to put the last of his renegade kinsmen from his mind.

A decade passed, then three years more. Helomon’s hair had touches of gray, and the strong line of his jaw was softening as the skin of his neck grew slack with waning middle-age. The knuckles of his right hand were swollen and misshapen from having been broken, his forehead had a long, narrow scar that clipped the top of his left ear, and he limped from an arrow-transfixed knee that had never healed aright. Yet whenever he passed, men of greater rank and authority did homage to the lion-cloaked Lord of Jaakhár for his deeds of arms were as famous as his vengeance was infamous.

Always at his side, in peace and war, at court or on the hunt, was Anukhepa, his bride, who men called Lady Black-Owl, though never to her face. It seemed the once-priestess still had Lord Death’s favor, for other than a single, silver forelock in her night-dark hair, and a web of small lines at the corner of her eyes, she seemed not to have aged at all. Nigh twenty years had she been the lord’s paramour, yet never had her womb quickened. Over the years, the clanwives and counselors fretted, summoned their courage and suggested that their lord might take bed a second bride, or at least bed a concubine or three, so that his succession might be assured. Those suggestions were met first with laughter, in later years scorn and then eventually wrath. But no other woman ever graced the Lord Helomon’s bed.

Xanthas Khol still lived, having settled at last in the ancient city of Tzukábaal, where he served as a war-chief to its decadent king and his elegant, young bride, whom all men said was the real power behind the throne. Kulkos’s failed revolt was long years passed, a new Great Speaker sat the throne, and Tzukábaal was a staunch ally of the Empire. Nearing sixty, Xanthas Khol was no longer young; his once dark hair, what remained of it, was long since gray, and he desired to return home.

The vast, closed curve of time was doubling back upon itself, and if Helomon had forgotten vengeance, others, both mortal and divine, had not.

V

The physicians said that had the honey-glazed strips of grilled peccary been poisoned, then many others’ in the lord’s retinue would also have been struck down, their muscles spasming, their faces twisting with rictus. But only Helomon was afflicted. The learned doctors debated amongst themselves and concluded it must have been slipped in the chilled chokátl he sipped each night after his meal, to settle a stomach grown riotous with middle age. Whatever the case, the lord knew the symptoms — and the prognosis — as well as his physicians: Within moments of answering Anukhepa’s frantic call they had looked at one another quietly, then regarded their liege-lady with sad shakes of their heads, unaware of either antidote or sorcery that might save the lord from his fate.

Some poisons work more swiftly – more mercifully — than others. Whatever passed through Helomon’s veins was slow, alternating violent convulsions with feverish weakness over the course of many hours, while leaving the Lord of Jaakhár’s mind crystal-clear. In his writhing, he envied those whom his vengeance had destroyed swiftly, whose bodies he’d hacked down in noble war, and he envied them.

Although the poisoner’s art was meant to hide the slayer’s identity from the slain, Helomon was certain that, hunted for nearly thirty years, Xanthas Khol had at last struck back; achieving through treachery what force of arms could not. Anukhepa was at his side, as she had been from the beginning; as she had been when he told old Sipan, himself now long dead and gone, that he would accept Xokolatl’s price. As Helomon looked at the sorrow and misery in his wife’s teary eyes, he realized that she knew Lord Death had at last called His debt due.

The price was his death…but in return for his vengeance. A vengeance that remained incomplete.

Clarity returned, and Helomon knew what must happen. The least exertion brought on the convulsions, but by speaking slowly, in the softest of whispers, he forced his dying lips to shape the words that needed saying.

Anukhepa and Ometl, Jaakhár’s seneschal, crouched beside him, listening to the whispered commands, until the death rattle came. Jaakhár’s lord was dead, and his face, contorted into a grinning death-mask, was horrific to behold.

Naakali wives keened at their lord’s passing; it was believed that the wailing not only released sorrow but frightened away the hungry demons that hovered about the dying. But Anukhepa, Lady Black-Owl, who was intimately familiar with Lord Death’s mysteries, simply kissed her husband’s cooling brow and sought to gently settle his face into an attitude of rest. Failing that, she sat back and hugged her knees close to her breast, eyes moist, though tears stubbornly refused to fall. When at last she spoke, her words scarcely louder than Helomon’s own.

“We must do as he bade. Send word to Xanthas-tzin that through the kinship of their fathers, with my Lord Helomon’s passing, Jaakhár is now his,” she said.

Ometl scowled, shaking his head in denial.

“My lady, he couldn’t have meant that! The pain…he was out of his mind with pain—”

But Anukhepa knew what must be done, though it felt as though the weight of it would crush her slender body. She breathed deeply, reminding herself that she had been Lord Death’s own priestess, and bride to His champion. There were deeds that still needed doing.

“No, Ometl,” she said. “For all he suffered, my lord husband’s mind was clear, even onto the end.”

“Then why?”

“By taking me to bride, and refusing other women his bed, Helomon foreswore himself any heir but Xanthas Khol, may the gods curse his name. Be the poison by his hand or another’s, the land, the fields, this palace — we, ourselves— are his to dispose of as he sees best fit. Summon him, Ometl, and see to it that he has safe conduct. Xanthas Khol will sit on the high dais of Jaakhár, as is his right. I will be here to greet him with the honor he is due.”

He clearly wished to argue, but training and caste won out over emotion. The frown never leaving his face, Jaakhár’s seneschal put a fist to his shoulder and bowed deeply to his mistress, then wordlessly withdrew. Anukhepa sat alone besides her slain husband, seeing not a broken body, but a young man she had met long ago on a dark hillside.

She lay there curled beside him for a long while, then drew from her girdle a small, obsidian knife, its edge far keener than the finest bronze. Kissing the blade, she whispered a prayer.

“The earth is a grave

which nothing escapes;

nothing is so perfect,

that it does not descend to its tomb.”

Nothing, not even love.

“My love, I shall finish what you began—”

V.

In the days that had followed Helomon’s death, the details of Anukhepa’s plan changed a dozen times, but never her resolution. Her husband’s slayer rode to Jaakhár’s gates, standing proud and tall in his chariot, bronze cuirass glinting in the midday sun, head crowned in a lord’s fan-crest of eagle feathers and jade plugs in his ears, a retinue of former exiles marching behind him. The Lady Black-Owl greeted him with all formality, regal and elegant in defeat as she knelt on the sand-strewn floor of the palace’s inner gate and offered him water and salt. Ometl knelt beside her, a ring of heavy bronze keys in his hand. Xanthas Khol accepted this symbolic submission with magnanimity, and stepping from his chariot, took the widow’s hands and lifted her to his feet, eyeing her appraisingly as he did so.

Face impassive behind a forced smile, Anukhepa led the lord through his new demesne, speaking with vapid enthusiasm as she showed him the frescoes with their leaping jaguars and dancing warriors, the central, three-tiered fountain and many other inanities and benign little pleasures her dead husband had either restored or expanded upon after the Rebellion. From the palace’s flat, rooftop garden she pointed out the orchards and maize-fields, babbling to the point of absurdity about the irrigation ditches, recently expanded by Helomon under the strict guidance of experts brought from distant Azatlán. Xanthas Khol smiled and nodded appreciatively, graciously listening to the woman’s prattle, disappointed that such a handsome creature, with such a fierce reputation, had clearly retreated into reverie for solace.

That night, a great feast was held to honor Jaakhár’s new lord, the citadel’s former mistress sitting beside him, insisting she cut his meat and serve him as she had the previous master. No fool, Xanthas Khol was reticent to eat, but the Lady Anukhepa laughed at his discomfort and made a point of having herself and Ometl taste of each dish first, from the candied orange slices that began the meal to the roasted turkey and grilled venison in chokatl sauce that were its centerpiece. Eventually, Xanthas Khol relaxed, and for the first time that day began settling into his role as lord and master. As the feast ended with dried and salted sweetbreads, he made a point of letting the lady carve slices of liver and place them directly on his tongue, and he in turn, fed her. What to do with the widow had posed a problem of decorum, but as they chewed and swallowed the organ meat together, he smiled to himself. Perhaps she needn’t go anywhere at all.

When the meal was finished, and the musicians sent forth from the hall, the new lord rose slightly drunkenly, Ometl escorting him to the chambers set aside for his pleasure. Anukhepa retreated to her own room. As a sign of his magnanimity, the new lord had allowed her to maintain the chambers she and Helomon had shared, but as she retired to the inner room, she noted that a pair of guards were set without her door. It had been subtly done, but it in the hours in which they had dined, Xanthas Khol’s men had stripped the chambers of both the dead lord’s war panoply and the trophies, small and large, that had denoted his many victories. Their many victories together. It was as if her husband had never lived.

Gone, too, was the obsidian dagger with its jade hilt — the tool of Jaakhár’s deliverance and Helomon’s final revenge. No doubt, even now, it sat with the poisoner, who laughed at her foolishness. All hope was gone, only the betrayer remained.

Thinking of what she had done, what she had eaten, Anukhepa gagged, then retched, making a mess of herself as she sought a chamber pot to catch her stomach’s revolt. When at last her roiling belly subsided, she stripped off her clothes, and throwing herself onto the thick, fur-covered petate sleeping mat, wept at last. Wept for her dead lord, for their lost lives, for the long-dead womb within her that had ensured this day would come to pass. Her heart felt dead in her chest, her liver swollen with self-loathing at both what she had done, and what she had failed to do.

Then her hand touched the soft little packet hidden amongst the furs, and she remembered who she was. The dagger was gone, but Anukhepa remembered that like the beasts of jungle and field, men had other, older weapons they might wield.

She had made promises; she would see them to their end.

“May the gods deny me either life or oblivion, if this poisonous dog escapes me,” she said to herself, unfastening her gold and feather coiffeur and divesting herself of her many ornaments and pendants, until she was naked and unadorned, but for the veil of her long hair. She took the small packet, wrapped in a cotton scarf, and slowly unveiled its bloody contents. At the touch of her bare hand, the heart convulsed, then began to beat with a slow and steady rhythm.

It was a marvel, if a horrific one, but Anukhepa felt only despair.

Looking about, she found a small lamp and set it on the floor. It was not her ritual brazier, but it held a flame, and if her will was strong, she thought it would serve. Cradling the bloody, pulsing organ in her hands, the once-priestess held it aloft and sang:

“The earth is a grave

which nothing escapes;

nothing is so perfect,

that it does not descend to its tomb.

“Xokolatl! Lord Death!

We, the Carrion Crows, are your servants!

Those to whom You have said;

‘May the Black Wind howl and Life wither

should the House of Xokolatl be disturbed.”

Anukhepa slowly squeezed her dead husband’s beating heart, carnelian-dark blood dripping into the brazier flame as she pronounced her curse:

Lord Death!

I give to you the man who has stolen the life

of Helomon, Lord of Jaakhár.

Mighty Xokolatl!

Take the life of him who has lived these long years

Only by your sufferance.

Lord Death consume him!

The flames blazed a spectral blue. Somewhere without her chamber, a cry rang out; a man’s howl of pain. Anukhepa paused, and the smile that curled her lips was as horrible as the rictus-grin the poison had painted across Helomon’s dead face.

I consecrate to you his limbs,

His head,

His brain,

His liver,

His lungs,

Keeper of the Black Wind,

Look down from your Throne of Bones,

Honor the pledge

You made Helomon long ago.

Blood for blood!

Flesh for flesh!

Heart for heart!

Life for life!

The bluish flames burned with a cloying, spicy sweetness beyond the copal incense, yet as the flames rose, the air grew cold. Anukhepa’s heart swelled. She was no longer alone; no longer afraid of what was to come. The cycle of her life was about to be complete. Lifting the organ to her lips she pressed them gently, lovingly, to the beating heart, and then bit into it with fine white teeth.

Blood spouted. Anukhepa shivered and cried out, her heart pounding like a war drum. She bit again, and again, each bite sending stabs through her own body. Through the pain, she realized that Helomon’s final command had not been in vain: Having received His due, the Tomb Lord honored his debt. Blood bubbling over her lips, she completed her task.

“The earth is a grave

which nothing escapes;

nothing is so perfect,

that it does not descend to its tomb.”

The dense fumes were now poison-sweet, but the air thick with frost. The tense, lithe muscles of Anukhepa’s body, still as firm and taut as a young maid’s, became limp as she fell to her side, one hand still clenching the bloody scarf that had held Helomon’s heart.

A shimmering mist glided about the woman’s body, drinking the power and the wrath and the exultation from her blood, growing thick and dark, until it became a pulsing whorl of shadow that pressed its way beneath the closed door and flowed, with the howling of an angry wind, through the palace halls.

Then the screaming began.

VI

All that night an evil wind blew through Jaakhára, so that good folk locked themselves indoors, and whispered prayers to uncaring gods. Those who dwelt within the lord’s palace suffered the greatest, as rafters creaked, roof tiles fell, and shutters were blown asunder — from within. In the days that followed, servants whispered that the wind had carried the pungent scent of meat gone bad and blew with a burning chill that struck to the bone. They spoke with trembling voices of a shapeless presence stalking the ancient halls, something made even more horrible for being felt, but never quite revealed.

Whatever the truth, with the dawn, all who had partaken of Xanthas Khol’s victory feast lay dead, but the citadel’s new lord most horribly of all: The heart had burst from his chest, the blood drained from his corpse, his flesh torn in thousands of little ribbons as if by an obsidian rain.

VII

Xanthas Khol, briefly Lord of Jaakhára, was dead, and the vengeance Helomon, Lord of Jaakhára and Anuekhepa Black-Owl his bride was complete. Lordship of the city was claimed by Kumenox, the dead lord’s youngest son. Having followed his father throughout his long exile, he saw the high-seat a just reward for his long service as Xanthas Khol’s right hand. Alas, his elder brother Paanchi, who had remained loyal to Clan and Empire, saw things rather differently, and ambushed Kumenox and all his court as they returned from a lion hunt. What he had gained through treachery, Paanchi now sought to rule nobly, and well he might have done so, had not a simple wasp-sting proven his undoing. He died much as had his cousin Helomon, face horrifically contorted and distended, gasping for air. Young and without issue, with his death, the ruling line of the Red Flower Clan was bred out, and the younger septs fell to squabbling, until the people of Jaakhára petitioned the Great Speaker in distant Azatlán to choose a new lord, of a new family, to rule over them.

The Black Wind had blown loose the last of the Red Flower’s petals. And deep in the Underworld, Xokolatl, Lord Death, most feared and misunderstood of all the gods, He whose touch brings both terror and comfort, Who rarely interferes in the affairs of Men, claimed the last of His price, welcoming all that noble fellowship into His halls.

________________________________________

Gregory D. Mele has had a passion for sword & sorcery and historical fiction for most of his life. An early love of dinosaurs led him to dragons, and from dragons…well, the rest should be obvious. From Robin Hood to Conan, Elric to Aragorn, Captain Blood to King Arthur, if there were swords being swung, he was probably reading it.

While a student at the University of Illinois in the early 1990s, he discovered that there was a vast collection of surviving technical works on fighting with the sword, rapier, lance and axe. Sword in one hand, book in the other, he never looked back. Since the late 90s, his passion has been the reconstruction and preservation of armizare, a martial art developed over 600 years ago by the famed Italian master-at-arms Fiore dei Liberi. In the ensuing twenty years, he has become an internationally known teacher, researcher, and author on the subject, via his work with the Chicago Swordplay Guild, which he founded in 1999, and Freelance Academy Press, a publisher in the fields of martial arts, arms and armour, chivalry, historical arts and crafts. He has recently started a column at Black Gate called Neverwhens: When History and Fantasy collide.

Greg lives with his very tolerant family in the Chicago suburbs.

Justin Pfeil is an IT Guy, draws a Webcomic, and fences with Medieval swords. He’s an Old-School RPG player and has been married to hiswife for 22 years. Check out his website for more!

Karen Bovenmyer earned an MFA in Creative Writing: Popular Fiction from the University of Southern Maine. She teaches and mentors students at Iowa State University and Western Technical College. She serves as the Assistant Editor of the Pseuodopod Horror Podcast Magazine. She is the 2016 recipient of the Horror Writers Association Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Scholarship. Her poems, short stories and novellas appear in more than 40 publications and her first novel, SWIFT FOR THE SUN, debuted from Dreamspinner Press in 2017.