BRONZE-ARD, THE FERRET MASTER, AND AUSPICIOUS EVENTS AT SWIFT CREEK FARM

BRONZE-ARD, THE FERRET MASTER, AND AUSPICIOUS EVENTS AT SWIFT CREEK FARM, by Adrian Simmons, artwork by Lilith Graves

The remarkable occurrence of both Bronze-Ard and the Ferret Master arriving on the same day at Swift Creek Farm presented Bellaw and her siblings with a rare opportunity to slip out of a day’s work. And, since the farm was blessed with plenty by the Goddess in the pool, Her sister spirit in Swift Creek itself, and Her brothers in the hills, all the chores ground to a halt.

Bellaw watched, rapt, as the traders and their helpers went about unpacking and securing their animals and goods. They would all stay, for the night at least, for that was the law and the farm was blessed with prosperity. If it was prosperous enough to pay for either of the services that the two travelers brought, that was a decision beyond Bellaw’s age and station.

Bellaw was uninterested in such matters anyway, such grown-up concerns like deciding if it would be better to have the team of barely-tamed polecats rid the farm of the rats and mice, if only for one spring, or if it would be better to have four fields plowed by the gleaming metal ard and thus save the wooden ones they had carved during the winter. To Bellaw, Bronze-Ard and the Ferret Master had brought something far more interesting with them–boys her own age.

Sons, surely, and bondsmen, traded for their services. Boys who had walked hundreds of miles and seen many things, and were just exotic enough to be interesting without being so foreign as to be frightening. They hadn’t even stowed their gear when Bellaw had narrowed her preference down to two: the reedy-tall boy in bondsmanship to Bronze-Ard and the easy-moving son of the Ferret Master.

She had to be careful about such things; broken noses and blood-feuds had started for less. So, as another cold and fitful rain began and everyone moved inside, Bellaw slipped up to the Goddess pool to ask Her advice.

It was improper, but she couldn’t help but find the Ferret Master’s offering of a polished and carved shell at the bottom of the pool, and not far from it what looked to be a wolf’s tooth from Bronze-Ard. She herself made the common offering of a pebble and whispered for the Goddess to give her a sign of some kind.

#

The Goddess, or as the people of the farm knew her, Helikkeel, wasn’t listening to Bellaw on that day, although she certainly did hear. No, this was the night to honor the First Agreement, and she coiled in a low slow spot in Swift Creek, listening.

“Destroy them, destroy them all,” urged Rabbit. He sat on the great flat stone that leaned into water, asking what he relentlessly asked. “Flood the valley as you have before. Wash them away and return the valley to us.”

Rabbit’s hatred of the men was unslaking. But he always asked the wrong questions, asked for things he could not possibly understand, so Helikkeel always said no.

Weasel came next, touching noses with Rabbit’s vessel as they passed on Truce Rock.

The polecat stood on the rock, scratched behind his ears then licked himself. Just a weasel, then, not Weasel Himself.

“Ask,” she prodded.

He popped up, made to bolt, stood very still.

“Men have my kind. Female. Female in sweet-season. Want to mate. Must get past was-wolves.”

She knew a hundred ways, and prepared to offer one that he could maybe understand, when he surprised her by asking:

“Make clever. Clever enough to get around was-wolves to female in sweet season.”

And, because it was within the bounds of the First Agreement, Helikkeel did so.

#

Run! Run! Run!

The weasel, Ate-Tadpoles, bounded from the safety of the trees and into the grass. Stop! Duck!

He waited low, sniffing. He popped up quick and sniffed the air. Smells of the old was-wolf were nearby, and of the man-stink and fire-smell and the musk of the strange weasels. It wafted on the night air from the house. Horses, too, and oxen, and other things. The female in sweet-season was there, too. Strong and sharp in his nose.

Hafta mate! Gotta get past was-wolves! His tiny brain reeled with the smells and the desires. Then he remembered it. The woodpile!

He popped again. The house was a massive blurry blob in his weak vision, and firelight glowed from its windows, and another blob in front of it was the woodpile.

Woodpile! Run!

Ate-Tadpoles shot through the grass, low and swift, keeping the strong scent of the was-wolf in front of him.

Gotta run! Gotta get to woodpile! Could die here!

The woodpile grew distinct in his nose and vision. He skidded to a halt there. Was-wolf was not far on the other side. Now he could make out the smell of pine-tar and horsehair that made up the was-wolf’s rope.

Hafta get past! Up to the big burrow! Hungry!

He was suddenly keenly aware of his hunger. His thoughts, his small scheme, all scattered, leaving only: Hungry! Could die!

He sniffed around the base of the woodpile. Wood and mold and dirt and old bark and… grubs!

Dig! Fast! Quiet- could die! He found a grub after making only a few scratches in the cold wet earth. Yanking it out of the ground he devoured it messily.

Why am I so close to man-burrow?

The wind brought him the answer. Sweet-season! Gotta mate! Run!

He ran from the woodpile to a smaller stack of wood and sticks and slithered in among them. It worked! The was-wolf was close, but didn’t smell him! Didn’t hear him! Other weasels covered him up! Man-sounds covered him up!

Next part hardest! Have to wait for exact moment! Have to wait! Wait…

…Zzzzzzzzzz…

Whoa! What? Gonna die?

He was in a woodpile. Near the man-burrow. The smell of sweet-season brought him back to his plan.

Run!

He ran up to the house itself. He’d never been this close. The men were making noises, lots of noises, like a stream over rocks but with their mouths. And the smell of weasels and fire was strong.

He slipped along the base of the house, sniffing for a way in. Rats found it, he could find it-

Freeze! Something moving around the curve of the wall ahead! Rooster!

The bird puffed up and lashed out its wings. Terrifying! Bite neck! Bite neck!

The was-wolf let out a deep bark.

Gonna die! Was-Wolf’ll get me! Run!

#

The icy rains started again the next day and kept both the Ferret Master and Bronze-Ard from working. And the day after it was still too wet, and Bellaw feared that the musk of ferret would never get out of the house. People slipped outside doing what tasks they could, just to get away from the crowding and the smell.

The musk made Bellaw’s feelings for the Ferret Master’s son, Walol, complicated. He was handsome enough, and clear-eyed and smart. But that smell… and he was lazy. Bellaw brought it up as she and her sister prepared one of the muddy fields for plowing.

“Lazy or ignorant?” Vanwan asked.

Bellaw’s foot caught on a stone under dirt that was trying its best to be mud. She’d have to pick that one up later. “What do you mean?”

“Not a farmer, is he?” Vanwan said. “Heard him tell that his great-grandfather went on the road with the weasels. Never plowed a thing since.”

“Not farmers? That makes no sense.” Bellaw pulled her ox and it trudged through the not-quite-dry ground. “Everybody is a farmer.”

“Kings aren’t.” Vanwan, for being her younger sister, was quick to point out Bellaw’s mistakes.

“He’s not a king.”

“He has a house by Leog’s citadel. Lives close to a king.”

“Not the same thing.”

Vanwan and the ox she was leading had a momentary disagreement about the direction and after a few hard pulls on the rope Vanwan won. “Rootless aren’t farmers.”

“They are so. They grow things up in the hills.”

“No, they come down here in harvest season, work, then they take some of the food back.”

Bellaw had feelings for some of the rootless boys, too. Delicious and forbidden feelings, steeped in taboo and simmered in mystery. But they were a poor folk, who may have farmed, but not the rich fat life she and her kind enjoyed.

“They don’t grow enough for a whole year,” she said to her younger sister, while quietly thanking the Goddess that those exotic boys did drift in to help with the harvest.

They prepared the ground with a few more passes of the oxen, then hobbled the animals and began to go through the field and gather rocks.

One field away, Bronze-Ard’s bondsman worked much like they did. At least he knew how to prepare a field for plowing, whether it was for a bronze-ard or a wooden one. The metal ard wasn’t going to get splintered and chewed up on the smaller stones, so Bellaw and her family could avoid digging those out of the dirt for a change. Of course, the smaller stones would wait for them, and bring their cousins up from below, next year.

“Either way,” Bellaw said, watching the bondsman guide the oxen, “Walol would make a poor match. Once he was out of the business of killing rats I’d have to teach him things about proper living that even a child knows.”

“Yes,” Vanwan said. “But that could be fun, too.”

They tied their baskets to the ox’s back and led him back into the field, picking up rocks, fist-sized or larger, piling them in the baskets, then emptying them on the field’s other side. Later they’d add them to the wall.

While her hands were busy with stones, Bellaw thought about the Ferret Master’s boy and watched Bronze-Ard’s bondsman. The young bondsman was tall, not quite Rootless tall, but close. The field he worked was just in front of Wild Hill, a little rise covered with brambles and great flat stones that her family never bothered to clear.

“Instead of making Walol into a proper farmer, you could go with him and travel with the Ferret Master,” Vanwan volunteered as they unloaded the third pass of rocks.

“Ugh… the smell…”

“Maybe you’d get used to it.”

“I don’t even think the Ferret Master gets used to it.”

Bellaw passed over a rock that was borderline size. “Now, the bondsman. He’d make a good match. Strong. Smart. Already knows how to keep a farm running.”

“Battle captive,” Vanwan said simply.

“He was very young, and he’s worked off his debt with honor.”

“He’ll have something to prove. They always do.”

“Maybe I could go with them? I wonder if Bronze-Ard would offer to take him on as a foster-son after his bondsmanship ends? Been known to happen.”

Vanwan didn’t say anything, which Bellaw knew meant she didn’t agree.

They worked in silence, clearing that field and then the next. Sometime in the late afternoon the bondsman hopped over the wall and pointed to the sky. “Do you think another rain is coming?”

They looked at the sky for a while. Clouds were coming in, again, and it looked like it could go either way.

Bellaw could see that Tolnal, Bronze-Ard’s bondsman, spent a lot of time looking at the sky, he had those kind of brown clear eyes–which reminded her of the rootless, which was nice. And he was growing chin-hair, unlike the rootless. Not a real beard yet, but something in between. It made her feel funny inside.

Rain or not, they had a lot to do, and spent another few hours prepping the fields before they all went down to the icy creek to wash off the day’s mud and dust.

Tolnal had nice legs, too.

#

Helikkeel was both in the creek, and the creek itself. She was in the Goddess pool, too, but only in a small part. And she was keenly aware that Ate-Tadpoles was back at the sacred rock. The sun wasn’t even down yet, and it certainly wasn’t time to honor the First Agreement again, and she was tempted to ignore him.

But he was close to the offerings, and that made her nervous. His tiny fuzzy mind might have the idea to steal something shiny from under the rock. Plus, just as water flowed downhill, Hilekkeel’s curiosity drew her back.

“I’ve granted your favor,” she said from the creek itself, “go back to your business.”

“Can’t get to weasel in sweet-season,” he chittered. “Get close. Not enough! Another favor!”

She knew where there were other in-season weasels, and it would have been the easiest thing in the world to tell him to just follow the creek for a day. But that wasn’t how things were done.

“GO!” she boomed. He jumped in fear, then slipped away into the high weeds.

She was about to go away when he came back and did it.

It hit the surface of the water like thunder, and as it slid down the few inches to the bottom her entire being shivered. It hit the pebbles along the bottom with a crunch like her cousins the boulders splitting from the mountains.

Her boneless toes dug deep into the tiny gravel and her claws pulled her forward to look.

A bronze arrowhead lay in the water. Ancient, still sharp. She could feel its two-hundred flights, see each nick and scratch and blemish–all adding to its majesty.

“Want a favor!” Ate-Tadpole said. “Want to figure out trick to get to weasel in sweet-season.”

And, since he had made the Offering, Helikkeel granted it.

#

Ate-Tadpoles was on his fourth attempt to get into the house when it struck him–this was his fourth attempt. Four. One less than the claws on one paw. It was an odd feeling. Like a smell he had never noticed but had been there all along.

The feeling left his mind almost as soon as it had entered, but it left a kind of track, a smell even, that lingered after. It cluttered his head with all the other things that had left thought-smells in his mind lately.

He slunk out of hidey-hole, where the metal bits that the Goddess valued so much where hidden, and then crawled through the brambles.

The offering had been a kind of thought-smell, too. Worrying and nagging at him as he slept. He had known about the metal almost all his life, he had known that men gave metal to the Goddess, but the idea that he could make the same offering was new. And, since he was now counting, and getting ever wilder schemes, he supposed the offering had worked.

Threading through the brambles, Tadpoles scurried onto one of the big square stones. His vision was poor, but from here he made the most of it. He spied on the farm for a while. Many of the humans had left, and this time they had taken the dogs with them. He popped, took a long slow sniff of the air blowing from the farm. Dogs, yes, but not near.

He jumped down, ran across the field to the rock wall, slid half over it, then looked and smelled. Turned earth and ox still lingered. He had no idea why the humans did it, but he had a thought-smell-trail that led his brain back to memories of watching them, the humans, leading oxen back and forth across the–Grubs!

He could smell them. So they were looking for grubs, perhaps? But they never ate any. Grubs for me!

Beneath the patchy snow the earth was wet and soft and no match for his claws. In moments he had dug up and devoured more-than-the-claws-of-one-paw worth of grubs and worms.

Birds had gathered on the wall, attracted by his success, and he left them to try their luck. He ran around the inside perimeter of the rock wall until the smell of oxen grew overpowering.

He checked the sky, to make sure there were no hawks with ideas, and then he scaled up the rocks, dropped down the other side and ran in among the oxen. He slipped around among their hooves, letting their powerful pungent smell cover him as he got closer and closer to the house.

He caught the muddy, matted tail of one ox and slithered up onto its back before it could swat him away. The big bull let out a moaning call of alarm that Ate-Tadpoles could feel vibrating through his paws. He broke into a run as the ox lifted his head to look back, ramped up the thick neck and jumped.

Beneath the melting snow covering it, Ate-Tadpoles discovered the grass that made the roof of the humans’ burrow was not just piled, but tightly woven–a complete surprise! For a few long moments he struggled, all his wet claws scrabbling among the thatch until he found one of the lateral-weaves and hauled himself up to it. He sprang up to the next one, then the next, and finally got to the very top of the thing, where the smoke-hole opened.

Thick dried mud and was packed around the thatch of the opening, and a couple of layers of old ox hide were tied on top of that.

Inside was a great drop that led to a barely glowing fire. The house was dim and smoky and Ate-Tadpoles could see the tin cages that the other weasels were in, against a far wall under the window.

There were furs and skins hung on a frame by the small fire. Tadpoles walked around the opening, looked, sniffed and built up his courage. He caught the smell of the female weasel in sweet-season and jumped with all his might.

Falling through the thin smoke, he spread his legs and flexed his claws then thumped onto the furs. They were damp and hot and not as soft as they looked and he slid down a bit before getting a grip.

He let himself down, nosed the furs aside, and slipped underneath them.

From his hiding place, he tried to get the smell of the room. There was too much! The dirt floors and the thatch roof and everything in between overwhelmed him.

He darted out from the furs and crossed over to the cages. They were all asleep, wheezing and snoring. Not these! She wasn’t here, she was… there! A smaller cage off to the side. He rushed up.

Sweet-season-smell washed over him, made all his senses swim and swoon. The thought-smell-trails in his head scattered like scents in a strong wind.

Bars! Cage! How to get in? He bit into the metal and pulled. Nothing. He shook it and she popped up out of her clay shelter.

She chittered at him for a moment: alarm and curiosity.

How did the humans get in?

Some of the other weasels were awake–they popped and ran to the edge of their cages and began pulling at the bars. The noise! Sweet-Season was alarmed and forgot about him for a moment and looked at the others. She looked back at him and started.

“Cat!” she chirped.

Tadpoles folded in half to look just as the big tabby charged. “Gotcha!” the cat yelped.

Tadpoles, thwarted so close to his goal, lost all the thought-smell-trails and jumped full into the tabby.

#

Cold and drizzly rain kept conditions wrong for either Bronze-Ard or the Ferret-Master to ply their trade. On the fourth day the men, those who lived at the farm and those who were visiting, went out to hunt the wild thigh-high ponies that lived in the glowering hills around the eastern end of Elskdale.

Bellaw’s day was spent in the dozens of tasks that kept the farm running, cumulating in four hours of separating good grain from moldy grain. How she hated separating grain. The idea of slipping away from Swift Creek with either group of traders grew more attractive with each hour she spent at the job.

The dogs set up a loud barking when the men finally returned. They had three ponies they had killed and Bellaw was eager to help butcher them– anything to get away from moldy grain.

She, her two sisters and her mother, were all elbows-deep in the job when Tolnol, Bronze-Ard’s bondsman, slid up to her. “Can I ask you a favor?”

“What?”

“I speared one of the ponies, and your father cut me a piece of its mane and said I should make an armband out of it. He seemed to think it was important.”

“It is. You have to honor the pony’s spirit.”

“So I braided it and then I asked your brother to tie it around my arm and he told me that the other tradition was to have a girl do that part.”

Because she was trying to cut the liver out with her stone knife, Bellaw’s arms were hot with blood and the heat of the pony’s lingering spirit. But her insides were tingly and cold as she looked at Tolnol. “‘First the braid, then the tongue’, it is an old tradition.”

“I’d like you to do it. When you get a chance.”

Vanwan snickered beside her and Bellaw gave her a shove with her hip.

“I’ve got to get the liver out and-” Bellaw started.

“We can finish up here,” her mother said, waving her bronze-knife in a dismissive motion. “You go and clean up.”

“Awww!” Vanwan began before a sharp look from her mother silenced her.

Bellaw walked to the small wooden bucket by the outbuilding and dunked her arms in and hurriedly rinsed them, then her hands, and dug out the bits beneath her fingernails. She could see Tolnol’s eyes had their far-away look, but a small smile touched his lips. He almost, almost, had a moustache.

“We always do the first rinse here,” she said nodding toward the bucket, “and then another at the goddess pool.”

They walked out back of the house and its buildings. The sun was nearing the western horizon and it lit Charred-Stones Hill with a light that drew out every branch and root and leaf-bud.

She dipped her arms into the cold waters of the pool, rinsing them a second time. Tolnol handed her the braid; he must have killed the little spotted pony. Not really something to be all that proud of, but she kept that bit to herself.

“So what is it like to travel far and wide?” she asked instead, tying the braid around his right arm.

And as the sun went down he told her, and he listened to her like she was the greatest of storytellers as she talked about what life at Swift Creek in the midst of Elskdale valley was like.

#

Helikkeel was fascinated by the goings-on at Swift Creek Farm. Most of the family and several of the visitors had made offerings and requests. They had hung three pony-hides over her pool. Then there was Fights-Cats. There had been, in her long existence, other animals that had captivated her, had asked the right questions, but he was remarkable. He had brought her two bronze arrowheads and a bronze spear-point. Untold wealth to a family like the farmers at Swift Creek who often chipped flint.

The older women at the farm had whispered to her that there was something wrong, some spirit or something, causing trouble at the farm. That was a supreme joke that Helikkeel couldn’t stop laughing at.

#

Fights-Cats watched the man-burrow. It seethed with activity like a stirred ant bed. Many of the men were busy in the fields, using the ox and some contraption of wood to dig for grubs. Birds feasted in their wake. Others, men and birds, were out in the woods, checking traps and picking berries. There were a few more inside the burrow, where Sweet-Season was.

He had been watching for a long time. So long that he could almost see the thought-smell-trails that the men followed. And, more importantly, he noticed that sometimes one of them would bring a weasel out and carry it to the wagon by the smaller workshop. The wagon had a bunch of wooden cages that held chickens, and a great clay jug–almost as tall as one of the wagon wheels. The weasels, although they strained for the chickens, were always put into the jug for a while, then carried back inside. That intrigued him.

It intrigued him that the men did things in a fairly routine way. Now, with the Goddess’ gifts, he could see that their chaotic behavior was generally ordered. And they brought the weasels to the clay jugs in the same order every day. And Sweet-Season always came last.

It was easy enough to slip past the dogs, and the rooster, and the cats had learned not to cross his path, and in full daylight Fights-Cats made his way to the Ferret Master’s cart. He jumped up to the wheel-hub and climbed up a spoke and into the cart itself.

“Polecat!” screamed the chickens, as they always did. “Gonna die!”

He ignored them and prowled around the great clay jug. The smell of pine and horsehair was strong around it from where it had been wrapped in ropes. But through it he could smell damp earth and… worms!

Yes. It made perfect sense, worms made more worms faster than chickens made more chickens, so feed the weasels worms. And knowing that… knowing that…

He clucked to himself as the idea hit him–an idea so clever that it almost ran out of his head like it was alive. All he had to do was wait until it was Sweet-Season’s turn, climb into the jug and then mate! He began climbing the ropes to get to the jug’s lid when a flaw in his plan entered his mind.

She might be too hungry to mate. That might lead to fighting, not mating. Which would not be how he’d want his plans to end.

Ah! He’d dig up worms for her, so she’d have plenty when she was put into the jug. Yes! Perfection! Just like he did with Goddess. He had seen men offer shiny things to her, and that had worked well for him. Now he would repeat the trick with Sweet-Season and the worms. Yes! An idea so sharp it had its own teeth.

But the ropes did something unexpected at the top–they twisted and folded around themselves in a weirdly tangled organized fashion.

No match for his teeth! He had already began to chew through the rope when it occurred to him that the men would notice… and now that he thought of it, they always did something with the rope first before they opened the jar.

One more question, then. He’d go to the hidey-hole and get another metal-thing and take it to the Goddess and ask her to teach him how to untie knots.

#

Bellaw spent her day knapping flint with her grandfather. The old man was making hammer-axes. They had a pile of two-fist-sized stones and he would chip one end into a blade, chip the other into a flat striking surface, and then do the complex operation of carving grooves along the sides. Now, in early spring, was the time to drive the new hammer-axes through the fast growing limbs of the trees so that by summer the wood would have grown and tightened around the grooves and they could harvest them.

She was in charge of making the rough blade straight and sharp. And she was embarrassed by the number of chips and misses she had marred them with.

While he didn’t appear to notice, her grandfather finally said: “Where is your mind, Bellaw? Not on the hammer-ax, that’s for sure. The stone will remember and resent this treatment.”

He wasn’t angry; his tone was soft and matter-of-fact. And he was right, the tools had to be shown their proper respect, as did the tree they would drive it through.

She stole a glance out to the field. Bronze-Ard and his team were cutting furrows with ease. Tolnol was out front, leading one of the ox teams.

“Bronze-Ard and his folk will be leaving tomorrow,” she said.

“We need the room. They need to go to the next farm.” Her grandfather was gnarled as an old root, and fierce, and proud, and he spoke blunt and short. But he favored her with a long look as his hands clipped and chipped the stone in his lap. “And why are you so concerned with when they leave?”

“I…” she started, then finally confessed. “I like his bondsman. We never got any time together.”

“The bondsman?” He snorted. “Can’t be too smart to be a bondsman.”

“He was young,” she said, then chipped a big notch into the blade she was working on. “And he did fine during the pony-hunt.”

“I had heard,” he said. “Ah, I miss the pony hunt!”

“I don’t even know where he is going next!”

He finished another groove. Still watching the work in his lap he said, “Perhaps, tonight you can find some time.”

“He’ll be tired from plowing all day.”

“Why when I was his age, and you’re grandmother had just moved in, the plowing was just the start!” He sighed. “I miss that, too.”

#

For the first time in a long while Helikkeel realized that she might not have been asking the right question. Men fought each other often and bits of bronze littered the earth. But… these points that Fights-Cats had brought her had not been buried. They were too clean, no dirt was in their grooves and nicks. Just where was Fights getting them?

#

The gorging-dream slipped from Kaalvaas’ mind. The taste of red flesh leaving his tongue, taking the smell of burning fat and the sound of shrieks with it.

The sound of metal grating on stone replaced it. And then laughter–a self-congratulatory clucking. And a smell, acrid musk and arrogance and the lust of furred creatures.

Eyes snapping open, Kaalvaas looked out into his den. The thief was a long-bodied creature, small like a rat, struggling to drag a spearhead toward the jumble of massive stones that used to be the North Gate.

Hatred, strong and familiar, burst into Kaalvaas’ mind. Muscles unused for centuries flexed and he surged through the bones of his kin and stretched his jaws wide to destroy the intruder.

The beast yelped, jumped, dropped the spear-head and ran. Kaalvaas closed his maw around empty air as the creature ran into the rocks. Hatred sparked the tinder of his belly and the flames blasted forth, bathing the rocks, the thief, the wall, Kaalvaas, the broken and gnawed bones, in a searing heat.

Thrusting his muzzle into the blocky stones, Kaalvaas took a great long sniff of the air. The fear-stink of the creature was strong, but there was no smell of burning hair, no cries of pain.

None yet.

He spun, a mass of coils and claws and wings. The treasure of kings that had been his bed seemed to be intact. But no, no it wasn’t. No! There were bits missing. The creature had snuck in and stole from him, from beneath his very nose as he had slept. This had the stink of meddlesome men who dared to match their greed and spite against his own.

The east gate was destroyed, but his nest-mates had been careful to pile the stones such that there was a small twisting path to the surface. Kaalvaas shoved through the rocks and tore through the earth and finally broke through the tangled roots of tree that had grown over the long years of his torpor.

Heavy night air bathed his scales as he slithered out. A bellow of rage formed in his throat, but he held it back. No. Best to get a feel for the land, for the men who had replaced the Great People.

His wings spread, greedy for the air and he sprang into the sky. No sooner was he over the trees when he noticed a house a very short way off. He coursed up toward the cloudy sky. A fat moon glowed fitfully behind the clouds, and in a few moments he had climbed high enough to see the full length of the Valley of The Seven Bravest, and into those valleys neighboring it.

The land was dark and dreaming. None of the lights of towers or great citadels glowed there now. Kaalvaas grinned, feeling the cold air whistle through his teeth. He and his brothers and sister had destroyed them all, as they had destroyed the great city. Destroyed it, killed and devoured all who lived there, burned it and the lands around, and then pushed down every wall and building to utterly erase the memory of the men from the land. Then he had devoured his kin, utterly erasing them from the world. He was the most cunning. He was the cruelest. All he saw was his.

But men had come back. He counted the hovels, none any bigger than the wretched huts so near his lair. Three here in the Seven Bravest valley, a scattering of others nearby. More than he could destroy in just one night. He hovered in the sky, draping his coils over and against one another as he looked and planned.

Then he letting the love of murder flood from his heart, he let out the war-shriek and dove at the miserable shack that marred his lawn.

#

At the western end of Elskdale, a good day’s walk from Swift Creek Farm, Bellaw’s closest neighbor, Lonlan, heard the sound. The indescribable sound carried to him on the wind. The whole family and their guests jumped at it. A noise like that had to mean something, something horrible and woeful.

His eldest boy looked over his shoulder at the great bronze-rimmed horn that hung on the south wall. They could blow the meeting call that could summon the different farms to the leaning stone at Mag Rufel. Lonlan’s hand shot out and he pressed his son firmly down. Any sound to answer that…even a roster, would only draw its attention. His old mother, silent as a cat, began scooping ash up in a cow-shoulder scoop and smothered the fire.

#

The Rootless, high in their hills and ridges, shuddered and wrapped their hides and skins tighter around themselves. Their shamans cringed and clutched their fetishes and waited, praying they would not hear the wolves.

The wolves heard, and the elders of their race started a high lonely howl. And those shamans among the rootless who could still understand such talk recognized it as the dread words. “It is time.”

Rabbit cackled in his den.

#

Bellaw was in the outhouse when the sound struck her. She cringed, raising her hands to protect her head. A silence as deep as the sea followed the noise and then it, too, was rent by a whooshing of air and then a splintering crash.

Her family, their guests, their pets and stock, screamed and bleated and yelped before being blotted out by another roar. Around the hide-door of the latrine a fierce orange light grew, matching the intensity of the screaming and crashing.

Her first thought, when she could think again, was to hide, to do anything but face the horror outside. Digging her fingernails into the wood of the bench, she had almost pulled the lid off and was prepared to follow her own dung.

Her brother was screaming long ragged yowls, nothing like words, nothing close. His meaning was clear: run. Run until your legs won’t support you anymore. Run until you drop. Run and don’t even turn to look.

The hide door was the only way in or out of the outhouse and Bellaw summoned what courage she could to pull it back.

The house, the house her grandfather and his brothers had built, was gone. The walls of wattle and daub were cracked and split and the roof was folded in. It was on fire. The very ground burned. A beast roiled and seethed in the flames like a monstrous bird in a great nest. The creature’s loops entwined the ruins, the bodies; claws dug into the flesh of her mother, wings fluttered and folded, fanning the flames. The creature’s head lifted high–as big as one of the great forest boars–lifting what was once her brother’s head and arm before throwing it back into the burning ruins.

Bellaw’s body, every bit of animal that she was, only wanted to run screaming into the night, but she couldn’t turn away from the grotesque sight. The poor dogs on their leads gnawed and strained at their ropes, trapped and waiting their turn. Somewhere out of the wreckage a man stood. Bronze-Ard, balancing on his one good leg, hefted his crutch and swung a mad blow at the beast, batting one of the great wings. Then… then… the thing simply engulfed him; coils and claws wrapped and swallowed him like a deadly wave. Bits of the burning house broke away and tumbled toward her.

One of those pieces was her sister Vanwan, running, burning, screaming. Bellaw sprang from her hiding place and swept her sister up to her. Vanwan seemed weirdly light, like the infant she carried following her mother’s skirts. Bellaw’s legs pumped, her feet pounded sinking into the damp earth and she flew to the Goddess pool. Crashing into one of the fresh pony-skins, she bore Vanwan into the shallow water and mud of the sacred pool.

She flattened herself and held her sputtering sister close; they had to hide, if it wasn’t already too-

The blow struck her through Vanwan. She could feel the great paw against her arm, hard and sharp and hot. It pressed them both into the soft mud, then it pulled at Vanwan. For a moment Bellaw held, but she might as well have tried to hold up a falling tree. Her sister was gone.

Hands that were not truly hands gripped her ankles and pulled her deep into the mud until she was sure the weight would crush her. She reached up into the burning light of the water’s surface, still grabbing for her sister. Something huge and horrible blocked the flickering orange light and then she was pulled down and away. She gripped, numbly, one of the pony skins.

There was a path, then a gate, and the mud became tiny gravel and Bellaw was borne into and born into Swift Creek.

The flat stone of the sacred rock was at her back and Bellaw vomited up mud and water and the last mouthfuls of pony. The slick flowed, illuminated by the light of her burning house not terribly far away, and spread slowly toward the edge of the stone where it dipped into the creek.

Bellaw’s mind moved slow as well, wrapping itself around the concept that this was a sacred place, sacred to Helikkeel, and that she shouldn’t foul it. She wrapped her arm around her vomit, the same arm that had held her sister, and scooped it back toward her. Her arm was cut open, a gash ran from her elbow almost to her wrist and blood flowed freely from it, mixing with the mud and water and meat–becoming the leading edge of the flow and clouding the lapping edge of the water.

She heard something move on the other side of the stone. She looked and saw a polecat ease itself through the high grass. Lifting its head it sniffed at her, and then lowered its head to look at her. Then it spoke.

“Did you bring Sweet-Season with you?”

The idea that a speaking polecat should surprise her didn’t occur to Bellaw after the night’s events. Instead she simply shook her head. Her mouth made words independent of her mind. “I think they all died.” After a moment she added: “They died with my family.”

The burning ruin of the house was perhaps five spear throws away. Somewhere beyond that she could hear the monster killing oxen.

The polecat sighed heavily and lay against the rock, looking like it was lost in thought. Then it scratched and turned to lick itself.

The trickle and rush of the creek changed its tone slightly and the hairs on Bellaw’s scalp pricked. Helikkeel was behind her.

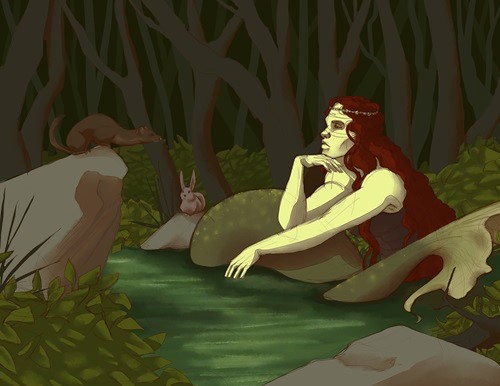

Turning, she took a look at the Goddess, the first time she had ever seen her. It was said the spirits of the rivers and hills most often appeared in dreams, and that perhaps once in a lifetime one might see them in the waking world. Helikkeel’s head was human–human enough–but the arms and body were something else. It was hard to focus on her, like looking through water, or smoke, or smoke in the water.

Helikkeel eased toward her, rattling the stones along the bottom of Swift Creek. Her appearance settled to that of a woman of indeterminate age, with long hair and breasts that had never felt the lips of a baby.

“A great and woeful thing has happened,” Helikkeel whispered. She whispered; even the Goddess was afraid. “I’ve fueled it,” she continued, then nodded toward the polecat, “and he sparked it.”

Bellaw was still shaking her head, short hard twitches back and forth. She could never rebuild the house by herself. Her mother had never showed her the fast way to carve pegs, and there would be hundreds of pegs. And the rope, and … and…

One of the oxen lowed as it was killed. And that was another problem. “… I really need those…” Bellaw managed to say.

The Goddess was right next to her, close enough that she could feel that her body wasn’t warm like a person’s should be. Bellaw forced her neck to stay still and forced her mouth to form words. “Help us!”

“I’ve done too much already,” Helikkeel answered. “He’ll probably come after me, now.”

Bellaw needed the oxen, and the hounds, and the chickens, and the walls and roof. She needed her family, she needed her brothers and sisters and her father and… and…

Helikkeel stated the situation firmly. “No family,” she whispered. “No help. No way to call the neighbors. They wouldn’t come if you did. They are too afraid.”

Helikkeel reached out and her chill hands wrapped the sopping pony skin around her shoulders. “An Agreement. Not friendless. Not without allies. Are you too afraid to whistle?”

To make such a noise- suicide! But the goddess of the pool, their goddess, would not have rescued her only to have her die here at the creek’s edge. Air sucked over her trembling lips the first time she tried, and the second. A squeaking note finally sounded and Bellaw cringed as she made it, fearing that it would hear.

“Just a bit louder,” Helikkeel urged.

Bellaw put her fingers to her mouth and blew out the long high note. The note that, before the first snows of the year fall, sometimes the cat-faced-owls answered. No owls called back; nothing stirred save the creek and the cries of oxen being murdered.

Three dogs, one hers and two that had followed the Ferret Master, slunk out of the night. They nosed at her, making sure she was alive. Helikkeel they acknowledged with lowered-heads and raised-eyes.

“And you,” Helikkeel said, lifting up the polecat. “Wakes-Terror, have any idea how to solve this?”

Bellaw watched the animal as it hung between Helikkeel’s fin and claw. His beady eyes glittered in the distant firelight and he might have been looking anywhere.

“In exchange for telling me where another sweet-season is?” he asked.

Helikkeel’s frog-mouth tilted in a lopsided grin. “Yes.”

The polecat looked at Bellaw, then the dogs, then the pony-skin, licking his lips.

“Yes.”

#

After killing all the men and most of the dogs and all the cattle, and after eating his fill after his long fast, Kaalvaas turned his attention to the one little man that had gotten away.

The smells of fire and burning flesh and hair overpowered any smell from the escapee. The fact remained: two had gone into the water here, he had pulled one out, but the other was gone. There was a tiny walkway that led toward the center of the pool, and propped against its end was a wooden plank covered with carvings.

This would have to be dealt with. The men still venerated those wretches?

Once he wouldn’t have trusted himself to be strong enough to beat one of their ilk, or clever enough to find it. Not tonight, not now.

He found the trail, the faintest one that led toward the creek, and followed it. Some of the hounds had escaped this way. Man-smell and rank pony-smell grew as he came upon the creek itself, but where they might have gone after that was a mystery. The scents died–or were covered–at the creek’s edge.

Dipping his head into the flowing water he could see the glint of metals gleaming at the base of the flat stone. Some of it was his metal. He scooped up a great mouthful and the water’s sound changed, like it wasn’t sure where to flow anymore.

His mouth full of metal, Kaalvaas slithered back from the edge, but she leapt–tail and all–out of the creek at him.

He lashed at her, his coils springing to catch her, his claws reaching to tear her. She was spiny and toothy and furious writhing. He tried to pull her further from the water, but she was too clever and turned soft and slippery and squelched out between his claws. With a snap of his neck he threw the spear-head and bits of bronze far into the field, but by the time he turned his fire back toward her, she was well under the water.

He burned at her anyway, at the water, at the stones, at the trees. Lips peeled back from his teeth as he waited for the steam to clear.

She pushed up to the surface. “Don’t touch my offerings again!”

“Such a small horde after so long?” he said back. “Did you think I would come and deal? That we could reach an Arrangement?”

She said nothing, just watched him with her great cat-eyes.

“There is double your poor pile in the ruins of the house,” he taunted, “further away than you’ll ever have the courage to venture. And no men will dwell here for a long age. Again.” He licked at the night air, tasting her fear and frustration. He could beat her. Kill her and devour her. Mate with her and sire beings to finally throw himself down!

She hissed, a low hateful sound. “A hundred trickles, a hundred pools full of riches. You have a long night ahead of you if you want to rob me.” And then she slunk down beneath the rippling waters to guard her meager horde.

Kaalvaas was no egg-toothed hatchling to let his small hatreds distract him from his greater. The one man was missing. The spirit had moved it here from the pool, but after that, where? Surely she didn’t have the power to move her out to another pool at one of the surrounding steadings?

For all her pettiness and weakness, she was right. His own great treasure was left unguarded, and he was eager to return his stolen goods, add to the horde, then hunt down the last of the miserable men and destroy the other houses in the Valley of the Seven Bravest.

#

Wakes-Terror made one last circuit around the ruins. The ruins were hidden, of course, he could see that now. Should have noticed that the rocks that kept the men from plowing here were too uniform to be natural. Of course, at the time, he didn’t quite grasp that the hidey-hole full of metals was bigger than the man-burrow he had been so intent on getting into.

“Courage, was-wolves!” he chittered to the three trembling dogs. They whined for the girl and begged for her to come back.

“No whining!” he snapped. “Remember to keep upwind until it is time. When it is time, remember the wings!”

He looped back through the thin passageway that the monster had left in its flight from its lair. It led down through the rubble, and he followed it until the cold wet-earth smell turned to char, then further until he popped out into the great chamber.

He bounded across the room to check on the weakest link in his idea. No, not an idea… something more. A plan. No… that wasn’t quite right, either. A strategy.

He chuckled to himself at the novelty of it. Not just reacting to the actions of others, not even anticipating them, but creating them. A wonder!

The girl waited where he had told her. She shivered under the dripping pony-skin. Did the Goddess have any idea how young she was? Still a kit! Should be eating tadpoles.

“Ready?” he asked her.

She jumped. “Is it here?”

“Soon!” he clucked.

Wakes-Terror would have to be more clever than she was weak, and more cunning than the monster was strong. The fur on his tail stood on end and he couldn’t help but dance about at the thought of what was to come.

He settled himself, then scratched behind his ear and licked himself. One more look at the girl and he ran to his hiding place.

Yes, he wanted to see what happened. Mating would be nice, too, but first this. Now all that was to be done was to wait and see, to keep on his toes and be ready to pop at the slightest…

…Zzzzzzzz…

#

Kaalvaas, high in the air, worried as he spiraled down to his lair. There was no sign of the missing man. None. And the spirit’s threat worried him. Surely if she had the power to send the man to another of the farms then she would have done a better job tangling with him at the water’s edge. Or was this just part of a greater scheme? But their kind didn’t really have schemes, they liked to make deals, set up arrangements and agreements. Perhaps he could take that big lump of bronze in the ashes of the farm and make a deal with her. No. That was his. He would bring it here to add to the rest, and look at it when he felt like sleeping to spur himself into hunting.

He also worried at the alarming conspicuousness of his lair. The dry brambles and dead leaves must have caught on fire when he tried to kill the thief. Fires still burned here and there. Maybe, his heart grinned, maybe the thief had been burning and left a trail of flame. That would be nice. That he would have liked to see. The youngling had run while her hair was on fire. That was good, but then the other had pulled her into the water and ruined it.

Hitting the ground with a thud, he settled his bulk and sniffed. Ash and fire, and the stink of dead dogs and burned men rose off of his scales like a perfume.

Holding the spearhead and arrowheads in his mouth, Kaalvaas nosed the stones aside, and pushed his way back under the earth. Before he came into the great hall he realized something was wrong.

He was halfway back out when the thief, the odd little rat-thing, scuttled across the flagstone floor, dragging a gold—a gold!–armband behind it and cackling like it didn’t have a care in the world.

Spitting out the bronze, Kaalvaas shrieked and surged forward, stretching his mouth open to unleash the fire.

The creature jumped then danced backward, cackling.

Something flashed just on the edge of Kaalvaas’ vision and the pathetic yelp of a man echoed again in the Emperor-To-The-Sea’s hall.

Pain, foreign and strong, blossomed in the corners of his jaws, the back of his throat and the base of his tongue.

He yanked back, crashing his head into the tilted lintel stone of the gate. A female, a youngling, swung a sword at his face, splattering him with his own blood.

Fire exploded out of him and the bleeding edges of the cuts in his mouth seared in pain. The youngling disappeared in the flames. Kaalvaas flowed out of the east gate and spread his wings, and the curs leapt out of the smoldering brush at him, leaping and tearing at the thin membranes.

He caught one in a bite, crushing its ribs. But his bite was weak and wrong, as if he bit too hard his jaw would break. The taste, the taste was wrong, too.

He threw the cur’s corpse aside, the other two dropping off of his wings as they turned to run. The joy of hunting and killing, of pursuing something smaller and weaker and terrified, overcame Kaalvaas and he turned to pursue them. Then the clucking chuckle of the polecat drew him back to the east gate. The creature came out, pulling something long and pink and bloody-tipped behind it.

It leapt among the rocks, capering and shouting. “Got your tongue!”

For the first time in his long fierce life a new feeling blossomed in Kaalvaas’ brain. Not fear–he had experienced that as a hatchling—but blind panic. The youngling, still alive, was climbing out behind its horrid pet, a steaming pony-skin tied loosely around her shoulders and that same bright-edged and bloody blade in her hand.

“Gonna die!” the polecat chattered. “Gonna die!”

Kaalvaas’ wings gobbled the air, pulling him and his writhing coils into the sky and to safety. The bites taken out of his wings tore a bit with each desperate flap; Kaalvaas didn’t care, didn’t care about wings or his tongue, or his treasure and the glory of his dead siblings; Kaalvaas cared only about what remained of his skin and what life remained him.

#

As long as she held the sword Bellaw felt better. It spoke to her, kind of. Assured her that fame and fury were hers as long as she kept its edges ground mirror-sharp. All the greatest heroes had swords that dreamed with them. Her grandfather had a leaf-shaped blade as long as her forearm, but it was a trophy from long ago, from when Loeg’s great-uncle fought the neighboring tribes.

This sword was as long as her leg, and made with an abundance of bronze. The cross-hilt could have easily been used to make a spear, or four arrowheads. She held it all night, in the cavernous hall that was under Wild Hill, and wore the reeking burned pony skin. It wasn’t a trophy, though, this sword. It was a tool, like the bronze-ard. The trophy was the tongue.

Although she had a choice of fine bronze daggers and axes within the old hall, Bellaw carried the tongue back to the farm as the first weak glow of sunrise grew in the east. She dug through the ashes until she found her mother’s simple straight knife.

She didn’t look at her mother’s body, or that of her brothers, sisters, and guests. Try as she might she couldn’t help but see, out of the corner of her eye. That was one of Tolnal’s nice legs thrown out by the woodpile. It hurt her far worse than the oozing gash on her arm.

She cut off the forked tongue’s tips and fed one each to her remaining hounds. Another bit, from the ragged root where it had run down the creature’s throat, she sliced off and threw to Herder-of-Horror. The next cut, a hand’s breadth of it from right behind the fork, she forced down herself. It was gamey and chewy, with a buttery finish.

“Would you like some?” she asked the Goddess. The sun was up, rain threatened as it had all these last few accursed days.

“A few drops. Yes.”

Helikkeel stood a dozen steps from her pool, looking as human as she probably ever could.

The girl nodded and got on with the task of slicing the tongue lengthwise, then butterflying it. The blood, thick and black, that oozed out of the spongy flesh she rubbed on the arrowheads and daggers that she was going to give to Helkeleel. She pounded the tongue flat, and then began rubbing it with powdered lime. She had no idea what to do with it once it dried. Normally you hung such a trophy from your belt, but this was long and would hang like a scabbard and be in the way. There was probably a way to make it into a scabbard, but that sort of knowledge had died with her father.

She couldn’t help but see their bodies, pieces of their bodies. Split from the heat, or torn in spite. Vultures waited in a lopsided ring around the house, watching her and her hounds.

She finished her work on the tongue and then walked to the edge of Swift Creek. Helikeel was waiting there, standing in the water, eerily beautiful.

“All along the edges of Swift Creek and its sister flows,” the Goddess said, “men have made offerings, men have asked questions. And the animals. They all heard the war-shriek. Some have long memories, some have good instincts. Many ask questions.”

Bellaw was not surprised. She dropped one of the bloody arrowheads into the water. “Where is it now?”

“I don’t know. Not in the water, or any of the water of mine.”

Bellaw tossed in another arrowhead. “Why did you never tell us?”

“I didn’t know. I was higher in the mountains in those days, and far to the east. Kaalvaas and his brood-mates were cunning.”

The water splashed around another arrowhead. “Will he come back?”

“If he survives, which he most assuredly will. His hate will keep him alive if nothing else.”

“The people who built the hall beneath the ground, who were they?”

“You call them the Rootless. They had roots here and in many other places.”

The Rootless. The strange tribes of the lonely hills.

“And do they know what’s happened?”

“Oh yes. Some of them.”

“And what will they do?”

“Those that are wise will seek out the one who had the courage to give Kaalvaas such a horrible wound. They will look for their–” and Helikkeel used a word that Bellaw didn’t recognize.

“It was luck,” Bellaw said, of her wild swing into the open kiln of the creature’s mouth. “Just like bridling a wild pony. Bronze-Ard’s last stand, that was brave.”

For the first time the Goddess took her eyes off the growing pile of bronze and looked at her and spoke the strange word again, slowly. “Empress. It means the queen from the west crags to the sea. I suppose that it means you.”

Bellaw had a hundred other questions, and the wealth to ask them. She ran her hands over the edge of the bronze-ard, watching the Goddess’ eyes caress it as well.

“The world has changed, hasn’t it? Beyond Elskdale. I feel it, like a great limb has cracked away and the tree leans a new direction.”

“Yes. Many things have heard the war-shriek.”

“This is not an offering,” Bellaw said, hefting up the ard, “this is a task. Protect it until a peaceable age comes back.”

If the Goddess was angered at being ordered around she made no sign.

The ard splashed and sank and the Goddess disappeared with it.

Bellaw walked back to the ruins, to find the dogs still snarling and snapping; vultures had come down from the high hills. Herds-Horror popped up and ran to her.

“The birds want to know why you keep them from their due,” he said.

“Tell them to go away.”

He chattered and they croaked in answer.

“They say their philosophers tell that the world was built as a gift to their race. They say all history supports this assertion. They have knowledge of the fate of dead flesh and say that by the time you bury them your family will be food for maggots anyway.”

“I’m going to burn them.”

“The vultures want to know why you hate them so, your family, to condemn them to be meat to be wasted.”

She looked at the vultures. Their black eyes glinted in the light, watching her. Vultures were dreamers, it was said, gifted by the gods with enviable time free of hunting and farming and the other necessities that cursed so many other creatures of the world.

She had been a good daughter, had done what her family had asked. She had followed the Goddess’ instructions, she had followed Herds-Horrors plan. Helikkeel had given her no further instructions, the polecat and the dogs and the vultures, and the spirits of her family all watched her, waiting for some kind of decision.

“Do their philosophers know where Kaalvaas has fled?”

After a round of chattering and croaking: “Of course.”

“Let me at least turn my family’s faces to their final sunset.”

She steeled herself, reached for the cold flesh of the people she loved, many she couldn’t even recognize anymore. One after another. She took a long breath and nodded toward one of the vultures. Another offering then. And an agreement. And a plan.

“Feast and be welcome.”

_________________________________________________________

If you’re at Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, then you probably already know Adrian Simmons. You want more? You got it. Wondering just what Frodo knew and when he knew it? Gotcha covered. Thirsty for a bit o’ the Irish? Let me pour it up, laddie! Desertification-eco-sword-and-sorcery? I’ll be your huckleberry.