WHITE RAINBOW AND BROWN DEVIL

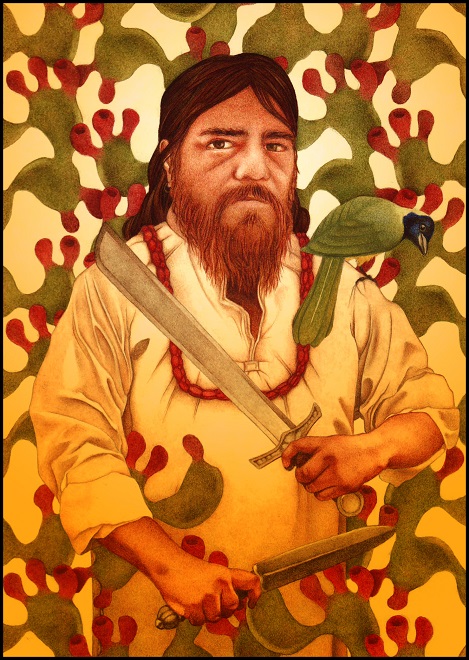

WHITE RAINBOW AND BROWN DEVIL, by Raphael Ordonez

Francisco Carvajal y Lopez, vagabond of the Tashyan badlands, conquistador in his own mind, emerged upon a caliche bank from thickets that sang sweetly beneath the sun.

The gravel floodplain stretched from north to south before him. Several sycamores, the first trees he had seen that day, grew down the center. A line of orange bluffs faced him from the far bank.

“Still no sign of them,” he growled, fingering the fishbone beads at his belt. “O Most Sweet Virgin, am I the victim of damnable perfidy yet again? With childlike trust have I followed Dacate’s word, seeking a modest recompense for all my sufferings in the painted canyons of the west. How many days has it been since I set out from the land of the Guequisales? Four? Five?” He raised the brown maul of his fist to heaven and shook it. “And where are these accursed canyons?”

Suddenly his eyes seized on a hint of movement. A shadow vanished among the white limbs and green pentagons of the largest tree. He grinned, gold teeth glinting, then slid down the bank and set out across the gravel.

He wore a few bits of armor, a cotton shirt, a loinclout of the same material, a leather jacket with a snakeskin girdle, and huaraches woven from grass fibers. Three blades swung from his belt, and an arquebus crossed his back in a leather holster, more useful as a club than as a firearm. His tangled black locks and long red beard gave him a savage look.

He drew up to the margin of the grove’s shadow and halted. A bowstring twanged. He put his brown hand to his head, and came away with a smear of blood and curly hairs. A mild but firm voice spoke from the leaves.

“I cannot understand you,” Carvajal called in Coahuilteco.

“All I said,” the voice returned, transitioning into the common tongue of the badlands, “was that I need not have missed.”

“Warning shot, eh?”

“I am here to keep the coyote-men from entering the land where the Quemzo live.”

Coyote-men! thought Carvajal. Did some escape? “Do I look like a coyote-man to you?” he growled.

“You look like the hairy buffalo, and you smell like the hairy buffalo with dung dried in its pelt.”

“And, like the hairy buffalo,” Carvajal returned, nettled, “I may seem docile enough, but I am dangerous when roused.”

The voice among the green pentangles sounded amused. “Go your way, brown devil. There is no place for you here.”

“No? I am a killer of coyote-men. I came here in pursuit of the last remnant. I can aid in the defense of your people. Would not that be of interest to your wise old man?”

“We are ruled by the counsel of Maikok Pepok, White Rainbow, our wise old woman,” the voice corrected. Then, cautiously: “Why would you aid us? For what return do you offer your help?”

“My only purpose in life is to rid the land of ancient evils. However, since you bring up the question of payment, I will mention that I have heard of a people who dwelt long ago in great painted caves in the land of the sun’s setting. I would see their dwellings, if I could.”

“You wish to visit the land of the Ulari?” the voice asked, curiously altered. “That is the reward you seek?”

“Let us not speak of rewards,” said Carvajal, who had learned that too open a display of the cupidity that drove him daily deeper into the wilds of Tashyas only provoked contempt among the Coahuiltecan tribes. “But I do believe it would be an appropriate gesture of goodwill.”

A slim young hunter dropped out of the tree, landing lightly in the drifts of leaves at its base. He bore a weapon with a richly polished wood handle and a crescent-shaped blade of blue flint. Like all tribesmen of southwestern Tashyas, he was built on a small scale.

“Your eyes are a liar’s eyes,” he said, “and you speak with a forked tongue. Where are you from?”

“I come from far away, over the Endless Water. I was born in an island kissed each morning by the sun’s rising. Setting out nine years ago with a mighty host, I sought the Fountain of Life in the land of flowers and crocodiles. Though cheated by that hope, I proved not faithless to my companions, but outlived them all. I seek now only to rid the world of evil.”

“Hm. If it were up to me, I would drive you from this land with arrows at your heels. But it accords with a strange command from Little Boy to take you into White Rainbow’s presence. If you aid us, then I myself will lead you to the land of the Ulari, provided White Rainbow does not oppose it. But know that what you ask may be more than you can understand.”

“Let’s go, then,” said Carvajal.

“I must tell the next watcher that I’m leaving a gap in the line. Wait here.” The warrior set off at a run, heading north along the dry bed.

Carvajal wandered back and forth through the shade. From time to time he peered out at the landscape. A line of gray-green hills came down from the north, but no eminence could be seen over the thickets that topped the western bank. For all he knew, the badlands rolled on forever.

The young man returned. “Are you ready?”

“What is your name?”

“I am called Peimemam Pamap Ketekui, the Star that Travels and Thunders.”

“Ketekui. I am Francisco Carvajal y Lopez, but my friends call me Moreno.”

“What do your enemies call you?”

“Moreno. Let’s go.”

#

For the hundredth time, Carvajal wondered how the natives of Tashyas could move so effortlessly past the clinging tendrils of thorny brush while the paths he chose seemed to involve him in insoluble difficulties. By keeping close behind Ketekui, he found himself almost gliding through thickets of guajillo, blackbrush acacia, and huisache.

Each step brought him closer to the desert. The spring flowers were mostly gone, all but the white-gold balls that tufted the sticklike blackbrush limbs. Here and there in the distance, a shriveled, dusty oak stood isolated in the plain. The hills to the north drew nearer.

“So, you’ve had trouble with coyote-men,” said Carvajal.

“No.”

“But you’ve had word of them.”

“A hunting party came upon them.”

“You told me that I’m summoned into the presence of your wise old woman…what was her name? White Cloud?”

“White Rainbow. Maikok Pepok.”

“Summoned by someone named Little Boy.”

“Pelawi Kikax, we call him in our tongue.”

“Who is he? Your…chieftain?”

Ketekui did not answer.

“What can you tell me about these Ulari?”

“They lived up the Atmahau Pakmat, the Great River, long before the Quemzo rose from the earth. The place in which they dwelt is a bad place, and we do not speak of it.”

Carvajal took this to mean that they were not going to speak of it, and tried a different approach. He drew out the single gold escudo that remained to him and began polishing it on his shirt. “I don’t suppose your Ulari had any such stuff as this,” he remarked.

Ketekui ignored him.

The land became drier by stages, until, to his surprise, Carvajal discovered that they had suddenly come upon a shallow yet fertile valley sloping down toward the southwest. He and Ketekui wound their way between patches of melon and squash and corn, crossing and recrossing the earthen acequias that watered them. Small butterflies danced in the brilliant air, drifting southward with the breeze.

“You’ve mastered the art of growing,” said Carvajal, surprised.

“It is the gift of Wakati K’nem Ma’at, the Great Mother,” said Ketekui.

Carvajal touched his fishbone rosary. “Does no one watch these plots?” he asked.

Ketekui hesitated, then said: “There should be people working them. The land is unquiet. Something has happened.”

The canals led them to the creek. It flowed southwestward between thickets of rustling reeds with an almost divine complacence. The planted patches continued beyond the far bank.

“This is the Ase Ma’at,” said Ketekui, “which wells up from a wound in the hills. It is our life.”

They turned down a path, following the water’s edge. Turtles with painted faces poked their heads above the placid surface. A heron swung by with lazy flaps of its wings. They entered a labyrinth of rattling river cane, a natural barrier easily defended by a handful of warriors. Carvajal reflected that it might have meant death to have threaded that maze as a stranger.

As the cane thinned, giving way here and there to patches of long grass and undergrowth, Carvajal saw that they were approaching a towering palm tree forest. Palms were, of course, a familiar sight in Borinquén, in Puerto Rico, the isle of his youth, but something about their massive, shaggy heads still filled him with foreboding. Perhaps it was the memory of their tossing in the terrifying hurricanes that swept over the island.

They emerged at last into the forest itself. Green jays and scarlet pyrrhuloxia flitted through the dappled sunlight, but they did not sing, and the scratch their talons made on the bark seemed almost noisy in the brooding stillness. Unease mounted in the back of Carvajal’s mind. He didn’t like forests. They were places where things watched.

The undergrowth receded as the canopy became more dense. The two travelers went noiselessly over a carpet of fallen fronds. The creek came back into view, broad and shallow. They crossed on the shoals, scarcely wetting their feet. “We must be close to a river,” Carvajal muttered.

“It is the Great River,” whispered Ketekui, “the Atmahau Pakmat. Forests of palms grow along its banks, all the way to the Endless Water, it is said. The palms end here, in the land of the Quemzo. Above this, in the land of the sun’s setting, the Great River flows nakedly past stony shores.”

Carvajal rubbed his beard. He had finally found the Río de las Palmas, the boundary between Tashyas and Meshico. For the first time since his shipwreck on Isla Blanca eight years ago, he had some inkling of where he was. Eight years of wandering, eight years of madness! Eight years of mosquitoes and dysentery! And only that one escudo to show for all his travails.

Suddenly, every bird in the forest took flight with a thunder of wing-beats. Ketekui tightened his grip on his axe.

They came soon upon a cluster of cane huts roofed with palm fronds in a glade. Women, children, old men, and old women stood around the firepit at the center. Several young men lay dead at their feet, their flesh torn with the half-moon marks of human teeth.

Ketekui hailed the people in Quemzo. They turned glazed eyes on him, then, as one, transfixed Carvajal with a glassy stare. Ketekui put aside their unasked questions by demanding to know what had happened. With groans they told him. Ketekui ran his hand over his face.

“What is it?” asked Carvajal.

“The coyote-men have come and gone. They bore away Maikok Pepok. Her trust in us was misplaced.”

“Hard luck.” Carvajal began cleaning the dirt from under his fingernails.

Ketekui questioned the people. The coyote-men had bounded into the village from the southeast, laid hands on the old woman, slain those set to guard her, and borne her away into the northwest, almost before anyone knew they had been there. The old men had given chase but to no avail. All this Carvajal gathered from their gesticulations.

Ketekui fell into abstraction. The people turned on Carvajal. Fearless in the shock of their loss, they surrounded him, poking and prodding and jeering at him, repeating words like pahuel and yatau and pamalap. Carvajal, who didn’t like being touched, began to get angry.

Ketekui uttered a command. The people fell away. He spoke at length, pointing to Carvajal.

“Listen, friend,” Carvajal broke in, “I –”

“I am telling my people of your offer. The gray slayers have taken Maikok Pepok beyond the boundary of our land, into the haunts of Yamal Xayepo, the Demon of Knives. We must track them down before he does.”

“But I promised only to aid in the defense of your village,” said Carvajal. “Much as I would like to accompany you, my journey to the painted caves will not wait.”

“The painted caves lie beyond the haunts of Yamal Xayepo.”

Carvajal tried to chuckle. “I’m sure there are more paths than one, my friend.”

Ketekui colored. “Will you aid us, or won’t you?”

“What? To rescue a dirty old woman?”

Ketekui turned away in disgust. The old men followed him into the largest hut. The children went off with their mothers. This left Carvajal alone with the old women. Their venomous glances began to make him sweat. But he didn’t care to leave the village until the coyote-men had gotten clean away.

Not for the first time in his life, he reflected that he’d acted with insufficient forethought. “O Most Sweet Virgin,” he complained, “once more I find myself beset by enemies. I came here in good faith, thinking you had paved the way before me. Instead I find myself inveigled in affairs with which I have no part, forced to choose between a vain expedition and the enmity of a vindictive people.

“You know that I am no coward, O Star of Morning. Did I not face Red Cloud himself in the land of the Guequisales? And have I not slain three, perhaps four, coyote-men? But my divine mission cannot be dragged down by the petty needs of every tribe in my path.”

He held up his hairy brown fist. “Only so much, O Queen of Angels. With only so much gold have I vowed to be satisfied. Have I not earned it tenfold through all my sufferings?”

“Are you talking to someone?”

He looked down, suddenly conscious of how loud he’d been speaking. A little girl with a solemn face and enormous black eyes met his gaze. “You speak Coahuilteco,” he said, with surprise and some displeasure. He didn’t like children. For some reason they always took him for a giant child himself, speaking to him as though he were on their level, which put him at a disadvantage.

“Grandmother made me learn it.”

“Grandmother, eh? She’s this Maikok Pepok, I’ll wager.”

“Yes.”

“Bah. Old women are all the same. Filthy beggars in their second childhood. More trouble than they’re worth. Yours is no different from the rest.” He spat, thinking of his own grandmother, a Taíno wisewoman, which always made him slightly lachrymose, giving him a headache and putting him in an ill humor.

The girl ignored his bluster. “You have tasted the waters of life in the land of the sun’s rising,” she said, not asking a question but stating a fact.

“What did you say?” he barked. “Did…Ketekui tell you of that?” He thought hard but couldn’t recall having seen the girl near him.

“Grandmother taught me the signs,” she said.

Carvajal did not wish to recount the Taíno stories of riches and life-giving waters that had first moved him to join the doomed Narváez expedition. Nor did he feel inclined to dwell on the undignified rites that had accompanied his drawing of the sacred draft at the heart of the great swamp. And the stripes he’d received upon his shamefaced return to the host of Don Narváez wriggled like snakes under his flesh. So he merely shook his head, and growled, “The water was bitter enough, and gave me one hell of a hangover, but from that day to this I’ve felt no new life coursing through my veins.”

“Feel?” she asked. “What would you expect to feel? You cannot drink such water and remain unchanged. You stand with one foot in the world of spirits.”

“Well, what of it?”

“The men will refuse to take me on this hunt. But I have to go. Grandmother wishes it. She wants you to go as well.”

“Didn’t you hear me just now? I’m on my way out of here.”

“Will you come into the forest with me? There’s something I want to show you.”

“I’m not so sure your people would appreciate that.”

“They know their place.” She took him by the hand and began leading him past the huts. One elder, seeing them, objected sharply, but the girl merely stared at him, and he retreated as though rebuked.

Well, thought Carvajal, it’s as good a way as any to make my departure.

They left the glade, bound for the dark heart of the forest. Dusk fell and silence closed in swiftly. “What is your name?” he asked, to get his mind off it.

“I am called Pakwa-ule Anekna.”

“What does that mean?”

“Raccoon Speaks.”

“Raccoon Speaks. Speaking of speaking, when your people were talking about me, they kept using a few words. I can’t remember them now.”

“They call you yatau because you are a brown man, and pahuel because you are like the devils who mislead hunters in the hills.”

“There was another…”

“They call you pamalap because you stink in our nostrils. How did you come to smell so bad? You must drive the game off wherever you go.”

“Well,” he spluttered, “perhaps you Quemzo don’t smell so good to me.”

“Is that true?” she asked curiously.

“N-no,” he admitted.

They came to a place where two rows of towering palms ran away into darkness, ending in a black covert shaded by thickest forest. Something stood there, watching them. Carvajal didn’t like it. Night brushed their heads like a descending curtain.

“Take me on your shoulders,” said Pakwa-ule. He obeyed unthinkingly, and she wrapped her legs around his neck. “Keep going,” she said, kicking his chest. He advanced down the aisle, wading through darkness.

“What is it?” he whispered.

The thing at the end loomed larger, a tall, thin figure of white-painted old wood. Three yucca grew at its feet, groveling supplicants with roots groping the earth like mummified snakes.

The face of the effigy held two black pits for eyes. Staring into them, he seemed to see twin sparks glittering in their depths…

#

His chest burned. For how long had he been running? Why was he running?

He’d been given to sleepwalking as a youth. One night he had come to himself deep in the jungle, where the coquíes sang like lost boys calling for help. He seemed to relive that now, experience the same slow emergence from a world of towering shadows and nightmares into a scarcely less incomprehensible wakefulness.

Moonlight blanched the landscape. The brush he ran through was sparser and shorter than it had been where he’d first met Ketekui. Patches of sand stretched between the thickets. The palms had been left behind, save for a few silhouettes set against a silver strip in the southwest: the Great River.

Pakwa-ule still sat astride his shoulders, driving him into the northwest over a low rise that would soon hide the river from view. Every so often, she compelled him to veer left or right by giving one of his fleshy ears a tug.

“Where are we going?” he gasped, his brain still too addled to grasp the strangeness of his situation.

“We are following Ketekui and the other hunters, as I told you.”

“They’ll only send you back, little girl.”

“They’ll not be able to spare anyone so near to the land of Yamal Xayepo.”

“Who does he have with them? Those old men?”

“Our elders. There was no time to wait for the watchers to return. A runner has been sent.”

Sensing his exhaustion, she allowed him to slacken his pace. He shook his shaggy head and blinked his eyes, but still he trotted forward under the girl’s direction, unable to muster the will to do otherwise. They came around a shoulder of the hills, which receded from view in the north. The land sloped gently downhill.

Carvajal descried a smaller river in a gravel floodplain ahead, its banks obscured by feathery vegetation, with a long, overgrown bar down the middle. Soon he was crunching over round white stones. They made him think of skulls piled in the moonlight.

Pakwa-ule drove him up to a thicket of catclaw acacia. Ketekui emerged from the greenery. “What are you doing here?” he hissed.

Pakwa-ule replied in Quemzo. Ketekui asked a question, and she responded with a single word.

“Come, then,” he said, throwing his hands up and returning to the thicket.

“You may set me down,” the girl said. Carvajal gladly complied. Still trying to catch his breath, he followed her through the screen of vegetation.

Ketekui and four elders squatted in the shadows. “Down,” he hissed. Then, to Carvajal: “Because my sister wishes it, I may allow you to prove yourself a man. Otherwise you must depart back into the east. What you may not do is blunder across the river on your own. If you do the least thing to give us away to our enemies — if you breathe too loudly at the wrong moment — I shall kill you instantly.” He brandished his blade.

“Grandmother wishes him to come,” said Pakwa-ule.

“He must choose it himself,” said Ketekui.

“I’ll come,” said Carvajal.

“Why the change of heart?”

“No change of heart. I’m just coming, is all.”

“I need more than that, my friend.”

“Don’t be so particular. I angered you this afternoon, but I didn’t break the terms of our agreement, did I? I had to look out for my own interests. Exactly as I am now.”

“That’s not how you spoke when we met.”

Carvajal grinned. “That was in my interests, too.”

Ketekui’s eyes glittered. “You smile like an opossum eating dung,” he said. “Just see that you do not hinder us.” He spoke a few words to the other men. They eyed Carvajal doubtfully but made no complaint.

They went to the river in single file. One by one they crossed the narrow channel to the island. They regrouped in the thickets, then crossed the far channel, making for a group of cottonwoods. Here they paused while Ketekui went forward to spy out the trail. Three elders and Pakwa-ule sat in a ring. The fourth stood watch.

Carvajal held himself apart, eyeing his companions. The watcher was a small, spry man with stringy muscles, like a strip of meat dried in the sun. Of the other three, one was very old indeed, and Carvajal imagined him a proud kinsman of Maikok Pepok who had insisted on coming and would prove a liability. The other two were somewhat flabby and, to Carvajal’s eye, indistinguishable.

He scanned the bleak landscape. Something warm dripped on the back of his hand. He rubbed it distractedly, and found it slightly sticky. Glancing down, he saw a smear that appeared black in the moonlight. Now a warm droplet fell on his forehead.

Slowly, he looked up.

The thing that had been a man grinned madly at him like a two-days-dead donkey, teeth thrust forward from lipless gums, lidless eyeballs glaring furiously, the nasal cavity a pit of deeper darkness in the blood-black death mask of its face. Its glistening hands reached toward him, dangling, as though it were a monstrous lemur clinging with its hind feet to the branch and wanting to play.

Carvajal stepped back a few paces. Calmly, he surveyed the spot. Two other skinned corpses dangled with the first, gently slapping one another like ripe fruit. A sodden patch darkened the ground beneath their outstretched hands.

“Look,” he whispered.

They followed his gaze. The elders groaned. Pakwa-ule said nothing, but rose and approached Carvajal’s side. “They’re all men,” she said, voicing Carvajal’s thought. “This is the work of Yamal Xayepo.”

Ketekui returned. “The signs are strange,” he whispered. “More than one party has passed here tonight.”

Silently, Carvajal pointed at the corpses. Ketekui gave no sign of surprise. “The Demon of Knives hunts men as some tribes are said to hunt jaguars,” he said, “more for the glory of the kill than for any good the animal can do their people. He takes man-skins as prizes. Their flesh he sometimes eats but more often discards.”

“How many coyote-men were seen in the village?”

“Some said six, some seven. Here are three. The others he may have killed and taken to devour at his leisure. Or he may still be in pursuit of them.”

“If some escaped, surely he wouldn’t have stopped to skin these.”

“N-no,” said Ketekui thoughtfully.

“And what of…?”

“I do not know.” Ketekui was silent a moment. “I will speak openly to you, Moreno, because you are a stranger, and to you, Pakwa-ule, because you would find out what I told him in any event. The others should not hear this. I do not believe White Rainbow is dead. She would not be worth…skinning or eating. If Yamal Xayepo had killed her, he would have left her body. It must be that he bore her away alive for his own purposes. He is a strange being. Though he has lived here long, we know little about him.”

“Did you pick up the trail?” asked Carvajal.

“Yes, and now I understand it. Let’s go.”

They continued into the west, across a rugged country of caliche bluffs. Yucca with long, curled leaves and stalks bearing red flowers sprawled here and there like octopi crawling over the moon-bleached earth. Squat cacti grew among the stones, waiting with cruelly hooked spines to cripple the man who stepped on them. The land rose and fell in rocky knolls and densely thicketed arroyos.

An escarpment like a lunar cliff came into view. The trail led them toward the mouth of a cleft whose sides were touched with the shuddering glow of a campfire. The towering shadow of a figure with an enormous head danced on the walls.

They went more cautiously now, slipping from thicket to thicket. Carvajal found Pakwa-ule sidling up to him. At the last thicket they all fell down of one accord and crawled forward on knees and elbows.

The camp of Yamal Xayepo came into view. A bonfire crackled wickedly in a ring of stones. Beyond this, a hut leaned against a rock face. Three gray man-skins had been stretched on the bluff. Two trussed-up bodies lay beside the fire. And Yamal Xayepo himself labored on a third with a crescent-shaped blade.

He reminded Carvajal of the crested caracara. His gigantic head was that of a bird of prey, with a hooked beak curled up in a predatory smile and a crown of feathers like the harpy eagle’s in the jungles of the south. But his ancestral wings had turned back into arms, a pair of short, feathered limbs with small-palmed hands and enormously long, thin fingers where the wing-tips had been. His scaly legs bent like a bird’s, and his feet were talons. Standing erect, he would be twice a man’s height.

Ketekui signaled to his companions. He wanted Carvajal to draw off the monster, allowing the others search the camp. Carvajal shook his head. He had his own reasons for not serving as the decoy. Ketekui stared at him with an unreadable expression, but said nothing.

One of the flabby elders volunteered. He crept out and ran across the edge of the campsite. Yamal Xayepo cocked his great head, rose, and strode silently after him. Carvajal and the others dashed into the circle of light.

Ketekui made for the hut and threw aside the flap. Within it, a cage of willow boughs held a small, hunched figure. The three elders mounted watch, their backs to the fire, while Ketekui set about releasing the old woman. Carvajal, ignored, knelt by the fire and began making preparations.

“What are you doing?” asked Pakwa-ule, who had remained by his side.

“That thing has already returned,” he said. “It’s watching us, wondering whether to attack or let us be. I’m going to convince it to let us be.”

Ketekui approached with Maikok Pepok, a small, elderly woman with a face like a wrinkled apple and a bell of coarse gray hair. Carvajal spat into the fire.

Several things happened in rapid succession. The decoy’s head soared out of the brush, passed like a meteor against the field of stars, and landed with an explosion of sparks in the fire. A glint of metal flashed through the night. The spry old man flew to the earth with a disc buried in his brain. Ketekui rushed forward, blade of blue flint raised. The Demon of Knives rose like a ghost from a thicket, one arm outstretched, the other about to hurl a second disc.

A deafening retort shattered the silence. Yamal Xayepo dropped from sight. The Quemzo fell on their faces in terror, all but the old woman and her granddaughter, who held onto one another.

Carvajal rose, dropping the arquebus from his shoulder, and strode into the thicket. Clouds of pungent smoke followed him. He returned a moment later, extinguishing the smoldering match cord with his horny hand. “He’s gone,” he said. “I hit him. He’s flesh and blood all right, but he’s still out there somewhere.”

“Can that…tube…destroy him?” asked Ketekui.

“If I get a clean shot. But I have powder enough only for one more, and he’ll be wary now. We outnumber him. What are our chances of bringing him down in an open fight?”

Ketekui eyed the surviving elders. “It is possible,” he said. “But I see no way of guaranteeing Maikok Pepok’s safety if we go hunting for him. He is a cunning and vengeful creature, and would gladly die if he knew he had extinguished the spirit of the Quemzo in his fall.”

“Flight is impossible,” said Carvajal. “He lurks between us and the stream we crossed. We’re cut off.”

“There is no help for it,” said Maikok Pepok. “We must cross the country of the Ulari.” Her black eyes glittered. “That suits you, does it not?”

To everyone’s surprise, he knelt before her and put his face to the earth. “Climb on my back, abuelita,” he said. “Let them bind you to me with thongs. We’ll have to push ourselves to the limit if we’re to escape that demon, and your withered old bones would snap under the strain.”

#

The sun rose high in the Tashyan sky, finding the party in a maze of baking box canyons. Ketekui led the way, avoiding dead ends and bearing west so far as the land would let him. He hoped to strike the Great River upstream, then follow its southern bank to the village.

Carvajal bore the old woman on his back, with the arquebus in one hand and the little girl beside him. The two remaining elders brought up the rear. They had seen no sign of Yamal Xayepo since the night before, but no one imagined that he’d simply let them go.

Heat, fear, and exhaustion put Carvajal in an ill humor. He grumbled under his breath.

“You growl like the badger, pahuel yatau,” said Maikok Pepok.

“Ha! You think yourself very clever, old woman, but I know what that means.”

“Do you?”

“You just called me ‘stinking brown one.’ Pakwa-ule told me.”

“No, I didn’t,” the girl said. “Have you already forgotten? It’s ‘brown devil.'”

“Whatever it is,” he spluttered, “call me Moreno.”

“What does that mean?”

“Brown devil.”

“You do not stink, Moreno,” said Maikok Pepok. “Perhaps my raccoon here has taunted you. To me you smell like the buffalo hide my grandmother used for the floor of her hut. A strong smell, but not a bad one.”

“Thank you,” he muttered. He glanced back. The two elders were still there. “Since you’re so wise, abuelita, perhaps you can tell me what this thing is that’s following us. Coyote-men I’ve seen. Giant bird-men are something new.”

“Coyote-men have the bodies of men but the spirits of beasts. They use deceit to trick the eye into seeing what is not. But Yamal Xayepo is what he appears to be. He comes from a race that wandered the earth before the making of man.

“Every kind of animal has given rise to its own people. One by one each enjoyed its day and then went into the night. But few of them have completely vanished. Yamal Xayepo is the last of the bird-race, cunning and cruel. Alone now, far from the land of his ancestors, beset by small hairless beasts, he grows in hate from year to year, but still does not die.

“I learned all this from my grandmother, and she from of old.”

Carvajal said, “This country gets stranger with every step.”

“Once, my grandmother told me a story of her grandfather, who traveled far into the land of the sun’s setting, many days beyond where we are now, beyond even Skull Rver, the Atmahau Xi, and into the Pelex, the Plain of the Unknown. There he found a stone mountain built by hands. The men who lived at its base could detach their heads from their bodies.”

“A stone mountain, eh?” mused Carvajal, stroking his beard.

“The Great River and Skull River wash many strange lands before they reach us.”

Carvajal glanced back again. The older of the two men had vanished. His companion walked on, oblivious. Carvajal halted and whistled shortly.

Ketekui turned and took in the situation at a glance. “How long?”

“A few moments at most. I just looked back.”

Ketekui put the question to the remaining elder, who seemed sun-dazed, and answered vaguely.

“What’s he saying?” Carvajal demanded.

Ketekui turned his gaze on Carvajal. “Did you truly hear nothing, Moreno?”

“Ask the old woman if you don’t believe me.”

Ketekui looked away. “I’ll go back for him.”

Carvajal caught his shoulder. “We’d better all go.” He hefted the arquebus. “This is the one thing that’s made that demon so shy today.”

“He speaks truly, Peimemam Pamap Ketekui,” said Maikok Pepok. “You will die if you go alone.”

“I do not fear my own death. What I fear is yours. You must pass on the spirit of the Quemzo.”

“You know that my successor stands ready. But if we go together, we shall all be safe.”

They hadn’t far to go, as it turned out. On a slab of rock they’d passed not ten minutes before, a heap of viscera lay piled like a stack of fruit in a pool of black blood. The flies were already beginning to gather. No other sign could be seen.

“From now on,” said Ketekui, “each of us keeps the others in sight.”

#

They halted under an overhang in the heat of the day. The canyon air shivered. It would have been suicide to go on. Carvajal sat with the gun across his knees, letting the sweat on his back cool him. They’d each drunk from a pool of rainwater cupped in the smooth rock floor.

They settled down to sleep. The remaining elder was chosen as first watch. He never roused his successor. It was late afternoon when the rest of them awoke. The old man had vanished. No one went looking for him.

They continued into the west, climbing, the old woman on her own feet now. The canyons became arroyos, the arroyos saddles between hills. Desiccated scrubland rolled into the southwest, toward the confluence of the two great rivers. Beyond that, the land rose up again in bleak wolds against a backdrop of pale blue peaks a hundred miles away.

Not a tree was visible in all that vast expanse, nor any moving creature, apart from three vultures lazily ascending a warm updraft, and the occasional rabbit in a stunted thicket. Ocotillo lifted their long, thorny sticks into the sky. Yellow-green beds of needle-sharp lechugilla filled limestone steps and shelves. Forests of sotol waved on rocky hillsides, each a long-handled bottlebrush of pale florets standing on a ball of spiny leaves in the golden grass.

An outcrop like the back of a cathedral came into view. Even from miles away, Carvajal could see the painting that adorned it, taller than the tallest tower, a blood-black winged figure, antlered and one-eyed, with a long, rectangular body, outstretched arms holding strange implements, and feet pointed downward in a shower of red oxide. Its ochre cat’s-eye glared at them no matter how their position changed. Carvajal felt its weight even when not looking at it. By an unspoken agreement, they circled far around it, but somehow that was worse, to be forever under the gaze of the far-away figure.

As dusk descended, he became aware that their path paralleled what looked to be the remains of an ancient road. It ran from east to west, a little to the north of their route. Once he even saw the ruins of a stone bridge spanning an arroyo.

“Why take the easy way when we can scrape our skins off in the brush?” he grumbled.

Ketekui overheard him. “That is the Path Where the Others Go.”

“Path Where — what? Others? The Ulari?”

“The Others dwell in the Dreamlands, out of time and out of space,” said Maikok Pepok, who was walking on her own feet at this point, “but their ways cast shadows in our world. To tread them is to leave the path of wisdom. For you it would be especially dangerous, Moreno.”

“Dah.”

They went on under the stars as the moon rose warm and yellow behind them, not making camp until midnight. Carvajal built a fire. He and Ketekui took it in turns to watch. Ketekui went first, quietly circling the camp in the moonlight.

“We’ve reached the country of the Ulari, I take it,” said Carvajal.

“They dwelt in the land between the Painted Rock, the Path Where the Others Go, Skull River, and the Great River.”

“Is this your first time here?”

“Once, as a young woman, I traveled up the Great River as far as the mouth of the Skull. None of our people have crossed the upland in five lifetimes.”

“Well,” said Carvajal, prodding the fire with the toe of his sandal, “if you’ve seen it once, I suppose you’ve seen all there is to see.”

“This land was green in the days of long ago. The rainbow smiled over the Ulari. In the end, though, they fell into worship of Yalui Ui, the Yellow Eye, a demon of the outer dark.”

“Yellow Eye, eh?”

“Pelawi Kikax vied with Yalui Ui. He sent his avatar to drive out Yalui Ui, and the people departed back into the earth’s bosom, never to see the light of the sun again. They dwell there still, under these silent hills. The land remembers them. It is not a good memory.

“In the land of the Ulari, all times are one. The past and the future meet like a willow bough bent in a hoop.”

“I thought perhaps that the bird-men had killed them off.”

“Yamal Xayepo appeared in our land in my mother’s time. He is said to have come from the south. The Quemzo, Yamal Xayepo, and even the Ulari are all clouds drifting over the face of the earth. The earth remains. One day, the Quemzo will be no more, our tongue silenced forever. Yamal Xayepo will go down into the dust. No one will know we lived. But the Great Mother, Wakati K’nem Ma’at, and Little Boy, Pelawi Kikax, her son, will remember.”

Carvajal grunted. Pretending to be deep in thought, he drew out his escudo and began buffing it on his shirt. Maikok Pepok watched him silently, her eyes glinting, then remarked: “The Ulari prized no such stuff as that.”

He kicked at the fire, throwing up a shower of sparks. “That’s just fine,” he complained. “Fooled again! What’s an honest man to do in a world full of liars?”

“The men who live in stone houses in the south are said to gather glittering stones as the Quemzo gather tunas,” she said. “Why do you not look there?”

He muttered under his breath. The truth was, being of mixed race, he didn’t care greatly for the conquistadors of Hispania, preferring to go it alone. He also had little desire to see his own still-palpitating heart dug out of his ribs.

“What of this…this stone mountain, where men doff their heads?” he asked. “Do they gather glittering stones?”

“Who can say? It may be.”

“And what’s your interest in me, old woman? Your granddaughter told me you wanted me.”

“It was the command of Pelawi Kikax, who speaks in my dreams.”

“Pelawi Kikax again.”

“He is called Young Coyote, and it is through him that the Great Mother made the world. That is the first secret, Moreno. They are Others, and dwell in the Dreamlands. That is the second secret. No doubt he was angered that the coyote-men mocked him by taking his likeness. It is he who wanted you. Pakwa-ule told me that you met him, and indeed that you and he had much to say to one another.”

“What?” grunted Carvajal, confused. “I don’t recall speaking to anyone.”

“You spoke long with Pelawi Kikax in the Place of the Three Yuccas.”

“That…thing in the palm forest? I…don’t remember saying anything.”

“Then it must be that Pelawi Kikax does not wish for you to remember.”

“Your granddaughter’s crazy, and you are, too, if you believe her.”

Maikok Pepok did not reply. The firelight danced in her black eyes.

#

The land dropped more steeply toward the two rivers now. Winding canyons barred the party’s path, not the crumbling ravines of the east, but deep troughs with overhanging walls of smooth, water-worn stone. This forced the party northward, back within sight of the road, which they had thought to leave behind.

Maikok Pepok rode on Carvajal’s back. Yamal Xayepo had not molested them, but Carvajal had seen him cresting a low hill behind them that morning. He said nothing of it to the others.

In the afternoon they came to a place where a stone bridge spanned a gorge. Even then Ketekui refused to set foot on the road. Carvajal swore in Hispanian and Coahuilteco, but Maikok Pepok sided with her grandson. There was no help for it. They would have to climb into the canyon and back out the far side.

Negotiating the smooth wall with the old woman on his back took Carvajal longer than he liked. It was the heat of the day when they set foot on the floor. They had descended to a giants’ staircase, with a wall of stone to their right and a sharp drop to their left. They decided to rest in the shade of the opposite cliff.

Carvajal watched while the others slept. He looked up at the bridge. “Savages and superstitions,” he grumbled, fingering the fishbone beads at his side. “You abandon me among one perverse people after another, O House of Gold, O Refuge of Sinners.”

He shifted uncomfortably, needing to step into a thicket. But then a thought struck him. He glanced at his sleeping companions, eyes glinting mischievously. They would never be out of his sight. He wasn’t abandoning his post. And, if they happened to wake up and see what he was doing, so much the better. Let them see what a civilized man thought of their Others.

Moving almost as quietly as a Tashyan himself, he got to his feet and began scaling the western wall. His huaraches gave him good purchase on the coarse limestone. Once at the top, he climbed to the bridge. But vertigo seized him as he set foot on it. His heart began to pound. His plan of going all the way to the middle became insupportable. This was good enough, however. He tested the wind, dropped his loinclout, and began urinating into the canyon.

Ketekui stirred and sat up. He turned slowly, saw the descending droplets, and followed them up to where Carvajal stood grinning. An expression of dread flashed across Ketekui’s face. Carvajal suddenly felt intense shame, as he usually did after playing the clown. Red-faced and angry, he finished and made to go back down.

Something gave him a violent shove. He flew off the bridge, tumbling headlong into a thicket on a shelf near the top of the wall. Thinking that Yamal Xayepo must have snuck up behind him, he sprang to his feet, raised his arquebus as a club, and waited. But no one came.

He climbed back to the top of the cliff. Something wasn’t right. Evening had already come. Had he been unconscious? The air, sweet and mild, smelled of rain. Had it rained? His raiment was dry, but droplets glistened like diamonds on the leafy scrub, which seemed somehow more lush and verdant than before.

Big pouches of cloud hung down like udders from the golden dome of the sky, glowing in the beams of the sinking sun. Gigantic bison cropped grass not a stone’s throw away. A double rainbow spanned the rosy curtains of rain in the east, and beneath it two hairy elephants tore mouthfuls of verdure from the earth with their shaggy trunks.

“Holy Mother of God,” Carvajal muttered.

He looked into the canyon. His companions were gone. No doubt they had abandoned him, possibly in dread at his ridiculous transgression. He swore under his breath, holstered his arquebus, and headed into the southwest, hoping to catch them before Yamal Xayepo did.

The canyon turned westward, cutting across his path again. He descended onto a promontory over its northern edge. Here he came upon a band of naked youths. They were chasing a giant hare with sticks, taunting it in a strange, singsong tongue, driving it toward a net stretched across a frame of bent boughs. Wild-eyed with fear, it leaped into the mesh at last. The boys converged on it, ululating viciously. They began beating it with their sticks.

Carvajal stepped up behind them. They started at the sound of his tread and turned as though caught doing something shameful. Blood spattered their hands and faces.

“What’s that you’ve got there?” he asked.

The boys smiled, showing strangely rounded teeth.

“What is all this?” he demanded. “Where are your parents? Have you seen strangers pass this way?”

The boys chattered at him in a language that was neither Quemzo nor Coahuilteco. Taking his big brown hands, they drew him toward the cliff edge. He complied, walking as in a dream. A sudden fear seized him that they would throw him off the brink. But they only guided him to a zigzag path that descended a narrow crack.

It was fully dusk when they reached the bottom. Fingers of cloud hung down from a ceiling of lavender and gray. Carvajal followed the boys west along a broad avenue of stone, through the occasional wall of brush growing along a seam in the bedrock, around big green pools that teemed with frogs and crayfish and dragonflies.

They came to a corner where the canyon turned sharply south again. The long, low gouge of a cave gaped like a mouth in the wall, its upper lip supporting the hill that climbed from its brink, its lower hidden behind slabs of fallen rock. The smoke of many fires drifted out like vapor from a dragon’s jaws.

The boys led Carvajal up to the shelter. Woven mats carpeted the floor, which formed a kind of enclosed landscape, little hills and valleys of dust that stretched around the curving mouth to the south. Paintings covered the low ceiling and back, writhing in the firelight.

A group of huts stood around each fire. Small people with long black hair poured out of them. They surrounded their guest and led him to a common area. There the painted designs spiraled in toward a square black doorway at the back of the cave, from which a short path crossed to the cliff edge. A pier of stone at a lower level projected over the canyon below, ending in a slab of rock like a table with a dark, shiny surface.

They seated Carvajal on a mat before the rock and proceeded to fete and feast him. A little drunk with the strangeness of it all, he accepted their hospitality with gusto. When they offered him a buffalo headdress, he donned it as a jest, and when they passed around a foul-tasting liquor, he quaffed it with the rest. He hoped for a chance to see what lay behind the doorway at the back of the cave.

But the potency of the drink overpowered his avarice. For a time — he never knew how long — he drifted in and out of bilious nightmares. An insidious chanting chased him down the avenues of his dreams. Emerging from this miasma, he became aware that the chanting hadn’t ceased. He was still in his place, before the smooth stone, but the fires had burned down low.

Sick to his stomach, scarcely knowing what he did, he lit the end of his match cord on an ember and began readying his gun. Something was coming, he felt sure. The people around him were all kneeling, intent on their summons. A single runner with a burning brand traversed the brink of the opposite cliff.

A red star twinkled evilly in the black sky beyond. It seemed to shine, not from the east, but through it or before it, as though the very cosmos were a mere backdrop, a picture that fooled the eye until something real and solid appeared against it. The star waxed. Carvajal discerned a figure in it now, a thing like a crucified six-winged seraph, a little larger than a man, arms stretched wide, legs pointed downward, glowing carbuncles in its hands and feet. A vertical pupil split its single yellow eye. Branching horns waved on its head.

Carvajal found himself pinioned. The people made to drag him toward the altar. But they had misjudged the effects of their liquor. He tore himself free, took aim, and fired. The recoil threw him back on his seat. The shot seemed never to reach the star-seraph; somehow it passed beyond it without going through it. Carvajal thought of the illuminated books in his father’s villa in Borinquén, and imagined himself a figure in one of their pages, trying to shoot at a reader.

Nonplussed, he let himself be seized again. The gun slid out of his grasp. His captors made him lean over the stone, his chest to its smooth face and his arms stretched wide. The star-demon drew nearer. Beams of red light burst from its arms and legs. They burned into Carvajal’s flesh, and his flesh drank them up. That gave the demon pause.

In a final burst of fury, Carvajal thrust back from the stone, sent one of his captors hurtling into the canyon, and broke the jaw of a second with the brown maul of his fist. He reached out and, somehow, made contact with the star-demon. Being a straightforward man, he throttled it. It began falling to pieces with an inhuman wail. Its head snapped to one side like a flower with a broken stalk. And then it vanished utterly.

Carvajal turned. The people were gone. In place of each stood a little mound of gray dust. The cave floor, naked now, sloped up to meet the painted ceiling.

#

The cosmic page wrinkled. A wave of disorientation roared past. He stood back beneath the bridge where he’d started. A bloody tableau spattered the white stone at his feet. Yamal Xayepo lay dead on his back, eyes glazed, one arm torn apart by a day-old wound, his high, feathered breast hacked open. Ketekui’s body lay across it, still gripping the blue flint blade of his fathers.

Maikok Pepok and Pakwa-ule sat in the shadow of the western cliff, as though just awakened out of the sleep in which Carvajal had last seen them. What sick dream had he been dreaming?

“Where were you?” the girl asked.

“What has happened?”

“The Demon of Knives fell upon us when you left. He and my brother slew one another.”

“I’m…sorry…I…something strange happened. Perhaps it was all a dream.”

“You stand with one foot in the spirit world,” said Maikok Pepok. “Your flesh is palpable to beings of other planes. I warned you about the Path Where the Others Go.”

“Yes, I…suppose you did.” He shook his head.

“Whether you will it or not, Moreno, your soul is sold to this land. When you came here, you thought you belonged to it no more than a man from the sky might. But you are part of its balance. It was always going to be you.”

“It’s more than I can understand, old woman.” Rubbing his head, he looked at the dead adversaries. Ketekui had given his life to protect the spirit of his tiny people. Not for the first time, Carvajal wondered what it was like to have a people. But he was also irritated that Ketekui, and not he, had slain the monster. “Well,” he said, “I’ll build a cairn over your grandson, if that’s agreeable to you. The Demon of Knives we’ll leave to the caracaras.”

“So be it.”

“Shall we retrace our steps, now that Yamal Xayepo is dead?”

“No. It will be easier to continue to Skull River and follow it down.”

With stones gathered by Pakwa-ule, he built a barrow over Ketekui on a high shelf. At Maikok Pepok’s insistence, however, he took the blue flint blade. He bound her to his back again, and they climbed out and continued on their way.

It was still late afternoon. No time seemed to have passed during the feast in the painted canyon. The land had turned dry and prickly again. The vegetation grew along the strata in gray-green stripes now, exposing the earth’s bones. Still, he thought he recognized its main features.

“What is it?” asked the old woman. He had slowed down. They were on the promontory over the canyon.

“I…don’t know. I…want to see what’s down there.”

“I would advise against it.”

“I just have to find out…”

“Go if you must, Moreno. Leave us here. Bur come back quickly, and, whatever you see down there, do not look back when you return.”

A few moments later he was jogging along the canyon floor, now a bone-dry white avenue in the afternoon sun. Though subtly altered, all was as he recalled. He reached the cliff shelter and climbed up. No sign of recent habitation remained. The level of the dusty floor had risen. Paintings still adorned the ceiling, but they were badly faded.

He ran along the cave, up and down the little hills and dales. Though damaged by flaking stone, the designs spiraling out from the doorway at the center were still visible. Gray dust choked the door itself. Scarcely half a foot showed below its lintel. Puffs of air made little clouds before it, as though the earth were breathing.

In feverish haste, Carvajal took up an ancient piece of basketry, fell to his knees, and scooped out a hole. He wriggled through on his belly, and found himself tumbling down a short slope. He rose to his feet and, as his eyesight adjusted, began to examine his surroundings.

He stood in a broad, level cave with a painted ceiling so low he could barely straighten his back. Its walls were invisible. An avenue lined with stones led straight ahead into darkness.

Advancing cautiously, he came to a double row of seated figures facing one another across the path, each a withered mummy with discs of mica glittering in its eye sockets. True son of Borinquén, he feared the dead at least as much as the living, and went forward with a dread so intense only his avarice could have mastered it.

It dawned on him that the cavern had grown less dark than he’d expected. Glancing back, he saw the doorway as a twinkling blue star. And yet, all around him, a gloomy golden glow played on the ceiling and in the skeletons’ eyes. The air moved subtly, resonating at times with an evil drone.

He came to the end of the seated figures, within sight of the cavern’s back wall, where a second square doorway, hung with a crumbling mat, glowed dimly in the murk. The mat swung gently in the puffs of humid air that wafted through it. Below it, he glimpsed rough stairs descending into a dim golden haze.

That was enough for him. He turned and ran.

He wriggled through the hole he had dug, and, eyes smarting in the sunlight, stumbled down to the stone altar. An object lay upon it, a ridiculously tiny skull attached to a long backbone curled up like a dead centipede and glistening with fresh blood.

Something whispered softly behind him.

He leaped off the edge, landed in a tree, dropped to the canyon floor, and ran for his life, never tempted to disobey Maikok Pepok’s advice.

The women did not ask to hear his story.

#

The sun was setting when they reached Skull River, a green flood crawling between towering cliffs of weather-stained stone. They surveyed the prospect from an ocotillo thicket.

“Ketekui has his wish,” Carvajal said. “He wanted me out of the land of the Quemzo. And here I am.”

“Are you not taking us back to the village?” asked Pakwa-ule.

“No.”

“How will Grandmother make it without you?”

“I am not going back either, child,” said Maikok Pepok. “You will return, and I will go on, into the Pelex with Moreno, if he will have me.”

“Whatever you like, old woman,” he said gruffly.

“My soul is yours, little raccoon, and yours is mine. So it has ever been with the Quemzo, and so it shall ever be. Follow Skull River to the Great River, and that to the village. Tell our people that the coyote-men and Yamal Xayepo are dead.

“I’m not long for this world. My spirit flags like the yucca moth’s. I will be dead ere the moon grows round again. I would see the land of the sun’s setting, as my grandmother’s grandfather did, before I close my eyes.

“And Moreno will lay me to rest beneath the fleeting stars, but he will go on and on and on, deathless, though he wish it not so, long after the Quemzo have vanished into the bosom of Wakati K’nem Ma’at. In the end he will curse the day he drank from the well of life. He will beg to die; will his wish be granted?”

Pakwa-ule replied in Quemzo, and for a time they spoke to one another in that tongue. Then, without a word of farewell, the girl turned to make her way along the brink of the cliffs.

“It’s too dark now to climb down to the river,” Carvajal growled. “You could have had that out at any point today, and saved us some time, but no matter. We’ll camp here and try it in the morning.”

“As you say, Moreno.”

And so Carvajal spent his last night in Inner Tashyas. For eight years he had wandered its beaches, fens, forests, and thickets like a fly trying to escape a sticky web. But it was only now, on the eve of his departure, that he knew he’d been drained dry by the spider long ago.

There would be no emergence from the Tashyan hinterlands, no triumphant return to Borinquén. Though he range from the jungles of the south to the plains of the north, his fate had been sealed since the day he partook of the deadly draft in the land of flowers.

The caballeros of Hispania had come here in search of god, gold, and glory. But Francisco Carvajal y Lopez was not a caballero. He was a callajero, a stray dog. God he had left long ago to others, and glory, too. Now disappointment had made even gold lose its luster. What was he to live for in its absence?

He pondered what Maikok Pepok had said. Carvajal the God had a certain ring to it.

Carvajal, the God of the New World.

Carvajal, the King of Infinite Space.

_______________________________________